By Marc Eliot Stein, World BEYOND War, July 31 2023

This is a complete transcript of Episode 50 of World BEYOND War: a new podcast.

It’s July, the hot summer of 2023. You know who I am, I’m Marc Eliot Stein, technology director of World Beyond War, still here in the Lanape lands of Brooklyn New York, still doing the right thing here on the World Beyond War podcast, Except today is special because this is episode 50, wow a round number.

When I started this podcast, I guess I never even thought about whether or not I’d ever get to 50 episodes. The number 50 sure wouldn’t have seemed realistic at the time. I guess I was mainly wondering whether I’d ever complete episode number 1, and there were a few close calls with giving up before I did.

And here I am at 50, and what a joyful thing it is, to realize that we figured out how to make this antiwar podcast actually work, and found an audience that grows every month. I am so proud of this podcast, and I’m grateful to everybody who has been a part of it so far.

Podcasting is a unique creative format. It’s not like anything else. I know this because I’m a podcast addict myself. I have at least 20 regular shows I really care about – about history, politics, technology, music, literature, TV, movies. When I’m in the mood to chill out and expand my knowledge at the same time, there’s really no other format that hits the way a podcast does. I think this is an important distinction: put a host and a guest into a webinar, say, or a livestreamed chat, and they’ll have one kind of conversation, but if you put the same two people into a podcast interview, somehow they’ll have a different kind of conversation – probably more personal, more spontaneous, more rambling, more in the moment, less designed to move towards a conclusion.

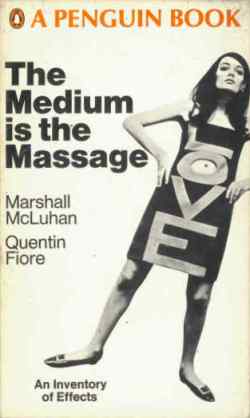

Why is this exactly? I don’t know, but the late media and technology philosopher Marshall McLuhan wrote something in 1964 about how rapidly the new popularity of television was changing modern society, and he was right. The medium, McLuhan said, is the message. The format is the content.

For example, you could write the same words on Facebook and on Twitter and on LinkedIn, and the words will carry a different particular meaning in each case. Since podcasts celebrate the spontaneous and unrehearsed human voice, podcasting has become a forum where human ambivalence or even perplexing contradiction and irony can be easily welcomed and understood. I guess this is a good forum to talk about a trend that’s very much in the news, and which I have a lot of ambivalent and perplexing thoughts of my own about to share with you today. I’m talking about artificial intelligence.

When Marshall McLuhan said the medium is the message back in 1964, back when few people were thinking about the subtle ways television and other intimate home-based broadcast media were changing the very fabric of human society. Today, a new medium enabled by today’s most up-to-date technology is also threatening to have a vast societal impact. I’m talking about popular general purpose AI tools like ChatGPT which are available to anyone with an internet connection – and if you haven’t heard about ChatGPT, it’s getting a lot of attention all over the place because of how well it emulates human conversation and how effortlessly it can integrate and retrieve the entire broad spectrum of available general knowledge.

Chatbots have been around for a few years – they can be as simple and innocuous as friendly automated customer service chatbots on a BestBuy or Ticketmaster website. New chatbots such as ChatGPT4 are not limited in scope to electronic products or concert tickets – these are very different types of knowledge engines, known as large language models, trained to grasp the entirety of human intelligence.

Sometimes people think the G in ChatGPT is for General, and this would be a decent guess, because the system is designed to demonstrate general intelligence and general knowledge. The G actually stands for Generative, which means that this product is also designed to create stuff – to generate original images and words. The P stands for pre-trained, which we’ll talk about in a few minutes, and the T is for Transformer, which is not a classic Lou Reed album but a software design pattern allowing the language model to respond to inputted texts not by processing one word at a time but by considering and running transformations on the entire inputted text as a whole.

These new chatbots can converse about any topic in a friendly, interpersonal, nuanced conversational style. The chatbots can write essays, solve problems, do deep database searches, generate computer code, instantly answer difficult questions. ChatGPT and other offerings like it show a level of linguistic and comprehensive agility that seems to move the field of artificial intelligence forward faster than many of us expected would be possible. There was a news story not long ago that some personnel at Google believed their own AI system could pass the Turing test and become indistinguishable from sentient human communication, spooking Google’s own experts with its evidence of consciousness. I don’t know if I personally believe any AI can pass the Turing Test, but I do know that many experts now believe this is becoming possible.

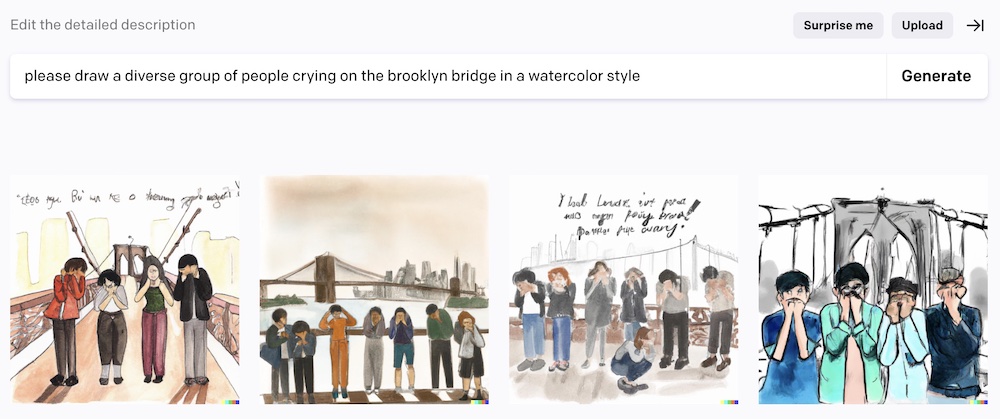

General knowledge chatbots are far from the only popular use case for AI. Image generators can instantly create visual artworks from text prompts – sometimes startling, clever images that would take physical painters or digital artists hours or days or weeks to create. Image generation from text prompts is a reality today via free online artificial intelligence image generators like DALL-E, from OpenAI, the same Silicon Valley company that created ChatGPT. You can imagine an idea and describe a painting style and this web service magically sends you a bunch of different variations of attempts to capture your idea.

This is a reality today, and It’s also a reality today that ChatGPT4 can write proficient, thoughtful, extensive essays on nearly any topic they are asked about – essays that might be good enough to earn advanced college degrees.

Maybe it’s too early to make a prediction like this, but it seems that intelligent chatbots and image generators – machine generated writing and machine generated art – represent a major tech innovation and a major societal innovation that will affect all of us on earth in one way or another. Who knows which way the future is going these days, but it seems at least possible that the launch of ChatGPT3 in 2022 will be someday remembered a significant moment in cultural history similar to the launch of the Mosaic browser in 1993, which kickstarted the entire popular Internet boom that we’re still living in today.

It also seems possible, I’m disturbed to say, that this new innovation will cause new kinds of major problems that we will all have to deal with, even though many of us may feel our society is already drowning in the unwanted after effects of other technological innovations that we didn’t request in our lives, didn’t invite into our lives, and yet which are in our lives anyway.

I want to spend this episode talking about how AI affects us as antiwar activists. Let me say this up front: AI is a hot topic, very controversial, and that’s as it should be. We should be worrying about it and we should be talking about it, and in my opinion we should also open our minds to the good that this technology can do.

It’s controversial among progressives and activists and it’s controversial for everyone. It should be controversial, and I’m not doing this episode because I have easy answers about how these recent innovations may impact our planet. I know they will impact our world, and I know that antiwar activists need to talk about it. So I’m doing this episode to get the conversation started, to lay out the various different issues that I think many antiwar activists are probably struggling with when they talk about this topic, and maybe to express some understanding of all the sides of this perplexing issues. That’s what I’m going to try to do here – and when you’re done listening to this episode, please do share your feedback on our world beyond war web page for this episode, or by contacting me directly – I’m easy to find.

In terms of impact on everyday lives, many wonder if the amazing capabilities of artificial intelligence will put lots of people out of work. This is often the first concern that occurs to people when they see the power of AI. Will these advanced capabilities cause various sectors of wholesome human employment and endeavor to become suddenly unwanted? Our society is already badly off balance in terms of who does the working, who does the earning and who does the spending. If middle class working-for-a-living ecosystems are further disrupted because AI can do many of the same tasks better and for free, we can be sure the disruption will increase the divide between the wealthy and the rest of us, that the 1% will be able to benefit from the change while the rest of us are left to face the consequences, and that the 1% will also make AI tools that help the 1% unavailable to the people who could use their help, or too expensive for them to access.

Let’s face it, in the predatory capitalist economies many of us are stuck living in, unemployment means going into debt and losing our freedom of choice, and this is exactly what these sociopathic fortress economies are designed to do to regular people – take away our power of choice and make us pay them and work for them. This is the future vision of fortress capitalism today: we’ll have newly intelligent and powerful computers, as we ourselves are pauperized.

There’s also the fact that police and military are already starting to use artificial intelligence tools, along with newly powerful and violent robots. I think this may be the most serious and immediate threat AI presents right now, and I think protest movements besieged by police like, say, the important Stop Cop City movement in Atlanta Georgia, are already dealing with this changed reality. AI systems carry the biases and coded values of their human creators, so AI trained police or military threaten to become literal hunting and killing machines for vulnerable populations, choosing their targets based on appearance or race. In a world that’s already raging out of control with war from Ukraine to Yemen, the idea of empowering one side or another – and, inevitably, both sides – with new kinds of murder machines and suppression regimes coded with vicious racial profiling is as horrific as it sounds.

The worst case scenarios for mass unemployment or racially coded artificial intelligence being used by police and military forces are horrifying, and we can’t sleep on this because the effects are already in our world. It’s already happening. So let’s just start this conversation by acknowledging that two of the separate horrors that advanced AI seems to present – mass unemployment and abuse by police and military forces – are two different ways that powerful forces of entrenched wealth and privilege steal rights and freedoms from the people.

Speaking of entrenched wealth and privilege – let’s talk about OpenAI, a company in Northern California which you can find online at OpenAI.com. This company was little known until they launched the DALL-E image generator in 2021, and then in November 2022, just nine months ago, they released their first public chatbot, ChatGPT3, quickly followed by the more powerful and capable ChatGPT3.5 and ChatGPT4, the versions available now.

I was pretty knocked out when I first saw the images DALL-E could create, and was knocked out even more the first time I tried ChatGPT. The challenge these tools were trying to meet was very familiar to me, because I’ve intensively studied AI myself, as many software developers have. My first encounter with artificial intelligence was an independent study project I did in college, quite a few decades ago.

This was the 1980s, and maybe some very young people will be surprised to hear that people like me were doing AI work in the 1980s, but the term artificial intelligence is nearly as old as the computer revolution itself. Even though AI achievements from the 1950s to the 1990s were infantile compared to the advancements we’ve seen in the years since then.

The field was so open-ended back in the 80s, in fact, that I was able to get a few credits during my senior year as a combined Philosophy and Computer Science major by cooking up an original independent study project for a program that would parse sentences in English and respond in a way that demonstrates or simulates basic comprehension. I coded in LISP on a hilariously bulky green-glowing Unimatic terminal connected to a massive Univac mainframe that was the size of a large building and probably had less power than the MacBook I’m recording this podcast on right now, because that’s how we rolled back in the 80s.

The exciting challenge of my AI independent study project was to parse and respond to sentences that included simple verbs and nouns. For instance, I would type sentences like “I have a cat named Happy” and “my cat is orange” and “all cats say meow” into my LISP program, which would demonstrate some comprehension by answering questions like “is Happy orange?” or “does Marc’s cat say meow?”. Amusingly enough, I was trying to create an AI chatbot right there on my Univac mainframe.

I bet many other college students were trying to do the same thing at the time, but none of us got very far, because this was the 1980s and one key brilliant idea hadn’t reached us yet: the neural network, which provides a software structure designed to carry out massively parallel simple operations similar to neurons in the human brain. While my LISP program provided single threaded computation, and Fortran and COBOL and Pascal programs followed the same limited single-threaded paradigm, neural networks provided parallel elemental threads that carried out simple computations in parallel. The human brain does a whole lot of parallel processing – simultaneous operations cascading to form illusions of singularity – and the software structure known as the neural network would allow coders to glean the power of this parallel processing – after I graduated from college.

Along with the concept of the neural network eventually came the concept of training a neural network with repetitive activities – another concept that hadn’t reached us yet in the 80s. I was feeding my LISP program a small number of complete sentences, and wasn’t giving it any feedback with which to correct and improve its performance. What I should have been doing, instead of typing sentences into my computer terminal, was feeding it entire books and newspapers and encyclopedias, and constantly interacting with it to provide feedback to its behavior as my program repeatedly attempted to simulate the most basic, primitive acts of comprehension. By giving it lots of reading material to build up a rich and complex knowledge base and training it repetitively and thoroughly, I might have actually gotten my computer program to say something surprising about whether or not I had a cat that was orange. Neural networks and repetitive training, it turns out, helped lead the way to the successful simulations of human intelligence that we see with chatbots today.

You’ll notice I speak of simulating human intelligence. This points to another controversy. Some people find the term “artificial intelligence” ridiculous. Worse than ridiculous, some find the idea ethically troubling because, if intelligence gives rise to consciousness, artificial intelligence can morph into artificial consciousness – artificial sentience, artificial willfulness, artificial right to exist. This sure as hell does call up many existential questions. All these questions are valid and important. Some wonder if AI knowledge engines and language models might already be developing consciousness. Personally, I find it pretty easy to declare that, no, we don’t have to worry about chatbots developing actual feelings. There are a lot of different aspects of AI to worry about, and this isn’t one that I personally worry about. But that doesn’t mean I can prove that I’m right and that nobody should worry about it. Maybe I’m just so overwhelmed by different things I should worry about that I don’t have time to worry about this one. I don’t have a definitive answer to all the questions that may arise about the questions of machine sentience, and I’m not going to pretend I do. But I do know what the questions are that we need to figure out how to confront.

One opinion I sometimes hear within activist communities is that AI amounts to a bunch of hype – an illusion fostered by a large language model’s excellent conversational skills. Sure, GPT can parse a question and respond in elegant phraseology, but why would this felicity with language make us imagine that some meaningful advancement has been made? Google and Wikipedia already made the whole of human knowledge easily available for free on the Internet, to the dismay of the Encyclopedia Britannica. We’re hearing all this hype about ChatGPT simply because it presents a linguistic facade of human consciousness, an illusion that we all fall for so eagerly. I think there’s some validity here. Maybe if Google or Wikipedia had originally launched in the kind of sudden and fully formed way ChatGPT did, maybe we would be talking about the launch of Google or Wikipedia as massive advancements in collective human intelligence, because both of them have impacted our world already.

Still, as I mentioned above when I talked about neural networks and training, to describe large language models as facades is to underestimate the layers of software structure that must exist to make this linguistic felicity possible.

Here’s a bigger question, in my opinion: let’s look into the ethics of OpenAI and its principals, founders and investors and partners. There’s a whole shitload of problems here.

OpenAI.com is a privately funded research laboratory emerging from the same ultra-wealthy and high-rolling Silicon Valley ecosystem of technology incubators that gave us Facebook, Google, Microsoft, Amazon and Oracle. Its founders include Elon Musk, the celebrity billionaire whose sociopathic public remarks really sicken me just about as much as they sicken many other people. Elon Musk was never directly involved in OpenAI, and he’s moved on to other things like displaying his offensive personality all over social media, so that’s all I want to say about Elon Musk today.

The way I see it, it’s even more damning that OpenAI is tightly involved with Microsoft, a major war profiteer, and a major profiteer in the field of artificial intelligence for war. This troubling association is what I hope people will worry about, even more than the Elon Musk connection. We should be very disturbed that the friendly face of DALL-E and OpenAI is a useful facade for at least one massively influential and evil war profiteer, Microsoft, which is already developing the kinds of racially-coded military and police artificial intelligence applications we talked about above. This is already happening behind the scenes at Microsoft and other US tech giants that are deeply tied to the US war machine. And this is about the worst news I can think of.

We in the antiwar movement can’t turn our backs on artificial intelligence because of its evil potential. I don’t mean of course that everybody in the antiwar movement needs to allow technological encroachments into their own lives. I’m glad many progressives and activists make a valid choice to avoid trendy tech innovations into their lives. I can relate to and respect this attitude, even though I’m far from a tech-free lifestyle myself. Technology is my field, my career, and as a technologist I’m fascinated by the genius and creativity and innovation behind endeavors like artificial intelligence.

Also, simply as a curious person, I am absolutely interested in gaining insights into human intelligence by learning about how computers have been made to simulate it. I also allow ChatGPT into my life because I’ve discovered how useful it is. I go to OpenAI.com and ask it questions constantly. I use ChatGPT to write code, including Javascript for a new version of our interactive map of US foreign military bases which I’m working on this summer along with other folks at World Beyond War.

Let’s say I want to clean up a query string parameter by removing special characters with a regular expression, which is something I would have used to ask Stack Overflow about, and I’d piece my working code together from recommended fragments posted to a conversation thread. Instead, I now tell ChatGPT what I want, and ChatGPT simply spits out perfectly formatted Javascript, executable and error-free. Most of my software developer friends use ChatGPT to write code now – I know we do because we like to talk about it. I don’t think any of us coders are worried yet that ChatGPT will replace us, because we are the ones who have to put the pieces of code together to create working systems, and GPT is just producing pieces of code. But I do wonder how this will change the way software developers work. It’s definitely already changing the game.

I also use ChatGPT to look up stuff online the way I would have used to use Google, and I use it for prompts and perspectives and background info on stuff I’m writing about or thinking about. I’m not kidding when I say I use it for everything – like when I mentioned the 1960’s technology philosopher Marshall McLuhan above, of course I asked ChatGPT for some info about Marshall McLuhan, and it’s ChatGPT who told me that 1964 was the year he published the book that said “the medium is the message”.

The fact that so many of us have already moved from Google to GPT for basic internet searches says a lot. It’s very easy to begin allowing these new kinds of tools to slowly and imperceptibly enter our lives, even as we worry about the implications and motivations behind them.

Like the underlying software technology of the Internet itself, which was created for dubious reasons by the US military but has gone on to cause societal changes and find new use cases that were completely outside the realm of its original purpose, this new technology is going to find its own path to impacting our lives. This new technology is real, it works too well to be ignored, and it’s here to stay. Again, that’s why I’m spending an episode talking to antiwar activists about it – because it’s already a part of our reality, and we may need some of the powers if offers in order to get our own work done here on earth.

Let’s spend a minute pondering the many aspects of life on this planet that don’t have the terrible problems we antiwar activists are so aware of. Arts, music, literature, biology, chemistry, physics, geology, astronomy, medicine, health, manufacturing, agriculture, nutrition. In all of these worlds, all of these endeavors … the public launch of a highly capable general knowledge chatbot is having a major impact. There’s no field it doesn’t touch.

On the plane of peaceful human coexistence – a plane that I wish I could spend more time existing on myself – artificial intelligence is a miraculous advancement of human capability that promises major benefits. If only we lived in a peaceful and safe and equitable world, we could better enjoy together the wonders that artificial intelligence can produce.

We see some of these wonders when we work with an image generator, and create stunningly clever or creative images based on our own prompts that we would not be able to produce otherwise. We also feel the paradox about whether or not artificial intelligence tools can be used for good. As a techie, I believe it’s not tech innovation that’s the problem on planet earth in the 21st century. I always welcome technological innovation, and I think the dangers AI presents are due to entrenched capitalism and war – to the fact that this is a planet at war with itself, a planet dominated by a wealthy 1% that can’t resist putting itself on the suicidal path of building militarized fortress societies that suppress other human beings to maintain privileges. What we need to do is heal our society – what we do not need to do is run away from technological advancements because we misunderstand the causes of our agony and our suicidal trajectory.

That’s what I think. Of course it’s not what every antiwar activist thinks, and that’s okay. We had some interesting reactions on the World Beyond War email discussion list – which is a lively and intelligent forum that I recommend anyone join, just click the link on our website or search for world beyond war discussion list – after someone shared some really imaginative antiwar images that had been generated with DALL-E, and someone else shared some surprisingly useful words about how our sick planet can find paths to world peace.

I believe that activists should master all available technologies – that activism should not put itself in the position of being less capable of using advanced innovative technologies than the corrupt governments and greedy corporations that are in the habit of oppressing us.

I also believe we can also glean surprising philosophical truths about human consciousness and human existence by studying the algorithms and design patterns used to model and simulate it. Just spending a few minutes fooling around with ChatGPT on the OpenAI website can reveal some wild truths about human nature.

Here’s one wild thing I’m still wrapping my brain around. ChatGPT sometimes lies. It makes stuff up. You won’t usually see this when you begin questioning GPT, because it will usually come up with a powerful answer to the first question in a conversational thread. GPT then keeps up with you as you ask follow-up questions, and here’s where it’s possible to sort of back GPT into a corner where it starts to straight up lie. One of the first questions I ever asked ChatGPT was to tell me about the best antiwar podcasts, because, naturally, my ego was engaged and I wanted to see if the World Beyond War podcast would show up on the list.

Now, since GPT is pre-trained – that is, it was pre-trained and is no longer being actively fed with up to date with very current news and information, so I wouldn’t expect it to know a whole lot about my little podcast. I also didn’t want to skew results by showing GPT that I was interested in one particular podcast, so I asked it whether there were any excellent antiwar podcasts and it assured me that indeed there were. I then started getting into specifics, hoping to prompt it to name the World Beyond War podcast by asking – can you tell me about podcasts which have interviewed well-known activists like Medea Benjamin. Here’s where stuff starts getting funny. Once the system makes a claim, it will try to back up the claim, so after it assured me that there were indeed podcasts that had interviewed Medea Benjamin I asked it to name one of these podcasts, and it then told me that Medea Benjamin was the host of her own podcast. Um, she’s not! If she was I would certainly listen to it. I was able to get ChatGPT to lie by backing it into a corner where it needed to provide information it didn’t have, so it made up information that sounded realistic.

This happens more often than one would think. You can also easily catch ChatGPT in a mistake by throwing true but contradictory information at it. After GPT correctly informed me that Marshall McLuhan’s introduced the quote “The medium is the message” in 1964, I remembered that this brilliant and sharp philosopher had also written a sort of ironic follow-up to his earlier book that addressed the darker and more troubling ways that media can put human minds to sleep, the scary populations of corporate mass population control through media – because Marshall McLuhan really was that awesome, he understood this danger way back then in the 1960s, and published another book in 1967 with artist Quentin Fiore called “The Medium is the Massage”.

So here’s where things got weird with GPT. I asked ChatGPT to tell me about Marshall McLuhan’s quote “the medium is the massage” … and GPT flatly informed me that McLuhan had not said “the medium is the massage” but rather had said “the medium is the message”. Clearly, GPT thought massage was a typo. I then informed GPT that it was incorrect and that McLuhan had indeed said both “the medium is the message” and “the medium is the massage”. As soon as I said this, ChatGPT realized its mistake and apologized and informed me that, yes, “the medium is the massage” was a book he’d written in 1967.

So why did it get it wrong first, and especially why did it get wrong when it already had access to the right answer within its reach? Well, here’s where GPT is starting to reveal surprising truths about ourselves, because in fact GPT’s two mistakes or misbehaviors made it seem more human, not less. Remember that G in GPT stands for generative. The system is designed to generate answers when it isn’t sure about the correct answer. It may tell you the title of a movie or a book that doesn’t exist – but it will be a title that seems like it could exist. If you have an open-ended, long conversation with ChatGPT about any topic you know a lot about, you will quickly see it start to make mistakes.

The way I was able to maneuver GPT into a corner by asking it follow-up questions to its own answers, eventually causing it to generate realistic seeming but false information in an attempt to back up its previous statements seemed not inhuman to me, but thoroughly human.

We see the blunt power of rhetorical and manipulative styles of argument here. Perhaps what we can learn from this surprising misbehavior of ChatGPT is that it’s humanly impossible to apprehend truth without fabricating truths in one way or another, and if we’re not careful these fabricated truths that we use for rhetorical purposes can become lies that we are forced to defend with more fabrications. Boy, this sure does seem lifelike to me.

Even more lifelike: we know that ChatGPT’s human like behavior includes lying. And yet we trust it! I even continue to use it myself, because, really, I’m self-confident enough to believe that I’ll always be able to detect when GPT is straining for an answer and generating false information. Hey, maybe I’m kidding myself, and maybe I should think about my own propensity to believe fabricated truths, and my own propensity to enable lying in others.

Here’s a way that GPT makes us smarter, by pointing out the ways we engage with untruth and facades and white lies and friendly deceptions in our normal human relationships. To put it in a nutshell: ChatGPT can’t simulate human behavior without sometimes lying. This is a hell of a thing for all of us to think about.

Here’s something else to think about: how are we humans doing in terms of keeping up with the tech innovations that define our societies? In the last few years, we’re adjusting to advancements in AI at the same time that we’re absorbing the invention of blockchain, a new technological method of building shared databases with new concepts of ownership, access and validation. We did a previous episode all about blockchain, and I personally feel pretty sure that most people I know still don’t understand the ways blockchain is changing our lives and will be changing our lives in the future – and now we’ve got large language models and general knowledge engines to change our lives and our futures too! Put this on top of, hmm … where do I even go here … the human genome project, vast advancements in brain science, the exploration and colonization of space … hey, fellow humans, are we keeping up with all of this?

Now let’s throw in the technological and scientific disputes over pandemics like COVID, and let’s not rest there but go on to consider the situation of widely available nuclear weapons in the hands of corrupt and incompetent so-called governments run by aging bureaucrats, and the politics of mutually assured destruction.

Are we keeping up with this? No, but this shit is keeping up with us, and it’s got our number. Every morning I wake up and read about the proxy war between NATO and Russia that’s been tragically murdering the poor human beings living in Ukraine. And every morning I wonder if this is the day the incompetence of our so-called leaders will cause nuclear war to begin – every day I wonder if this is the last day for human life on planet earth.

It’s the hot summer of 2023. There’s a new movie out called “Oppenheimer” about the scientist whose work led to the incredible horror of the instant murder of hundreds of thousands of human beings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki Japan in 1945. I don’t think any of us have yet managed to expand our own minds enough to comprehend the absolute evil, the shocking, unendurable truths of the mistakes our societies have made – and of our failure to improve ourselves and raise ourselves up from our pathetic, shameful societal addiction to mass hatred and mass violence.

I mentioned above that some people ask whether or not artificial intelligence can lead to consciousness and/or sentience – whether an AI system can ever develop emotions and feelings, and what these words and these questions even mean. I haven’t seen the movie Oppenheimer yet, and I feel pretty sickened by the idea of a movie about mass murder in Japan that doesn’t show the faces of the Japanese victims. Instead of wondering whether or not AI systems are sentient, all I want to say is that every single person incinerated in Hiroshima and Nagasaki was sentient and conscious. That’s a truth I don’t think we’ve managed to face up to yet. Maybe we need to train our own minds on this one a little more.

And that’s where we end today. Humans can’t handle the truth about the problems we’ve created and the changes we need to make to improve ourselves. Bots can’t handle the truth either. Thanks for sharing this space with me as I ponder the mysteries and ironies of human existence, and I’m going to take us out with the human voice of a singer and songwriter I’ve loved for a long time, Sinead O’Connor, and a song called the Healing Room. Thanks for listening to episode 50. I’ll see you back soon for 51.

World BEYOND War Podcast on iTunes

World BEYOND War Podcast on Spotify

World BEYOND War Podcast on Stitcher

World BEYOND War Podcast RSS Feed