(This is section 42 of the World Beyond War white paper A Global Security System: An Alternative to War. Continue to preceding | following section.)

The International Criminal Court (ICC) is a permanent Court, created by a treaty, the “Rome Statute,” which came into force on 1 July, 2002 after ratification by 60 nations. As of 2015 the treaty has been signed by 122 nations (the “States Parties”), although not by India and China. Three States have declared they do not intend to become a part of the Treaty—Israel, Sudan, and the United States. The Court is free standing and is not a part of the UN System although it operates in partnership with it. The Security Council may refer cases to the Court, although the Court is under no obligation to investigate them. Its jurisdiction is strictly limited to crimes against humanity, war crimes, genocide, and crimes of aggression as these have been strictly defined within the tradition of international law and as they are explicitly set out in the Statute. It is a Court of the last resort. As a general principle, the ICC may not exercise jurisdiction before a State Party has had an opportunity to try the alleged crimes itself and demonstrate capability and genuine willingness to do so, that is, the courts of the States Parties must be functional. The court is “complementary to national criminal jurisdiction” (Rome Statute, Preamble). If the Court determines that it has jurisdiction, that determination may be challenged and any investigation suspended until the challenge is heard and a determination is made. The Court may not exercise jurisdiction on the territory of any State not signatory to the Rome Statute.

The ICC is composed of four organs: the Presidency, the Office of the Prosecutor, the Registry and the Judiciary which is made up of eighteen judges in three Divisions: Pre-trial, Trial, and Appeals.

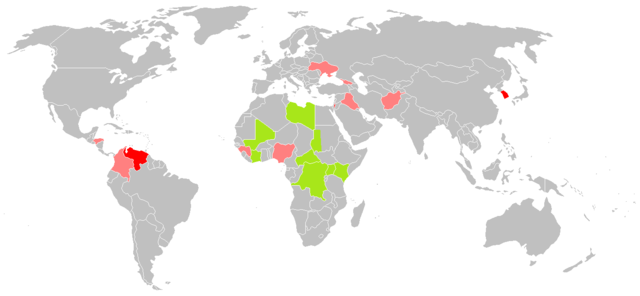

The Court has come under several different criticisms. First, it has been accused of unfairly singling out atrocities in Africa while those elsewhere have been ignored. As of 2012, all seven open cases focused on African leaders. The Permanent Five of the Security Council appear to lean in the direction of this bias. As a principle, the Court must be able to demonstrate impartiality. However, two factors mitigate this criticism: 1) more African nations are party to the treaty than other nations; 2) the Court has in fact pursued criminal allegations in Iraq and Venezuela (which did not lead to prosecutions) and of the eight investigations currently open (2014), six are non-African nations.

A second and related criticism is that the Court appears to some to be a function of neo-colonialism as the funding and staffing are imbalanced toward the European Union and Western States. This can be addressed by spreading out the funding and the recruitment of expert staff from other nations.

Third, it has been argued that the bar for qualification of judges needs to be higher, requiring expertise in international law and prior trial experience. It is unquestionably desirable that the judges be of the highest caliber possible and have such experience. Whatever obstacles stand in the way of meeting this high standard need to be addressed.

Fourth, some argue that the powers of the Prosecutor are too broad. It should be pointed out that these were established by the Statute and would require amending to be changed. In particular, some have argued that the Prosecutor should not have a right to indict persons whose nations are not signatory; however, this appears to be a misunderstanding as the Statute limits indictment to signatories or other nations which have agreed to an indictment even if they are not signatory.

Fifth, there is no appeal to a higher court. Note that the Pre-trial chamber of the Court must agree, based on evidence, that an indictment can be made, and a defendant can appeal its findings to the Appeals Chamber. Such a case was successfully maintained by an accused in 2014 and the case dropped. However, it might be worth considering the creation of an appeals court outside of the ICC.

Sixth, there are legitimate complaints about lack of transparency. Many of the Courts sessions and proceedings are held in secret. While there may be legitimate reasons for some of this (protection of witnesses, inter alia), the highest degree of transparency possible is required and the Court needs to review its procedures in this regard.

Seventh, some critics have argued that the standards of due process are not up to the highest standards of practice. If this is the case, it must be corrected.

Eighth, others have argued that the Court has achieved too little for the amounts of money it has spent, having obtained only one conviction to date. This, however is an argument for the Court’s respect for process and its inherently conservative nature. It has clearly not gone on witch hunts for every nasty person in the world but has shown admirable restraint. It is also a testimony to the difficulty of bringing these prosecutions, assembling evidence sometimes years after the fact of massacres and other atrocities, especially in a multicultural setting.

Finally, the heaviest criticism laid against the Court is its very existence as a transnational institution. Some don’t like or want it for what it is, an implied limitation on unconfined State sovereignty. But so, too, is every treaty, and they are all, including the Rome Statute, entered into voluntarily and for the common good. Ending war cannot be achieved by sovereign states alone. The record of millennia shows nothing but failure in that regard. Transnational judicial institutions are a necessary part of an Alternative Global Security System. Of course the Court must be subject to the same norms which they would advocate for the rest of the global community, that is, transparency, accountability, speedy and due process, and highly qualified personnel. The establishment of the International Criminal Court was a major step forward in the construction of a functioning peace system.

It needs to be emphasized that the ICC is a brand-new institution, the first iteration of an international community’s efforts to assure that the world’s most egregious criminals do not get away with their mass crimes. Even the United Nations, which is the second iteration of collective security, is still evolving and still in need of serious reform.

A civil society organization, Coalition for the International Criminal Court, consists of 2,500 civil society organizations in 150 countries advocating for a fair, effective, and independent ICC and improved access to justice for victims of genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity.note44

(Continue to preceding | following section.)

We want to hear from you! (Please share comments below)

How has this led you to think differently about alternatives to war?

What would you add, or change, or question about this?

What can you do to help more people understand about these alternatives to war?

How can you take action to make this alternative to war a reality?

Please share this material widely!

Related posts

See other posts related to “Managing International and Civil Conflicts”

See full table of contents for A Global Security System: An Alternative to War

Notes:

44. http://www.un.org/wcm/content/site/undpa/main/enewsletter/pid/24129 (return to main article)

3 Responses

We better get busy. We are going to need a strong ICC to help the US out of its web of International Criminals. Never more urgent to have a strong ICC than Right NOW.

Um i like the poster it’s on canva. can i come to the nato festival i will need a ride there tho can someone give me a ride

We have a rides and lodging board https://worldbeyondwar.org/notonatolodging/