On the International Day of Peace, remembering a pioneer in nuclear disarmament and the evolution of humanity away from war.

by Roger Kimmel Smith, September 21, 2018, The Progressive.

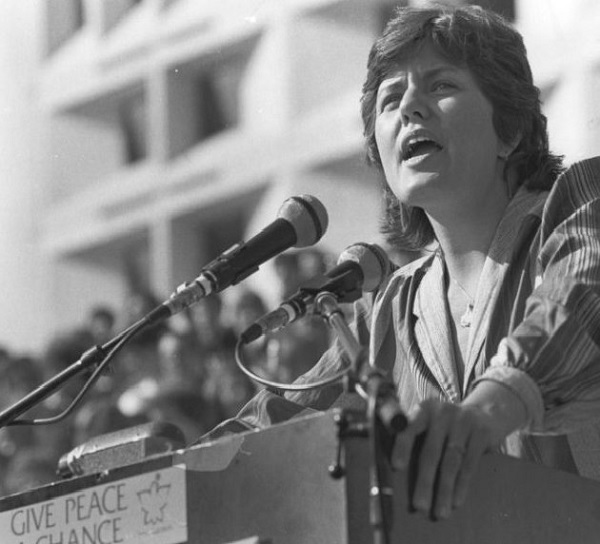

When the disarmament scholar Randy Forsberg issued her “Call to Halt the Nuclear Arms Race” in 1980, it was the right idea at the right time. As nuclear fears rose with the incoming Reagan Administration, her proposal for a U.S.-Soviet bilateral freeze on nuclear weapon deployment, production, and testing captured the public imagination. The freeze campaign of the 1980s ballooned into the largest grassroots anti-nuclear movement in U.S. history.

Some movement voices critiqued the freeze proposal, arguing that it stopped well short of true disarmament, let alone banning the bomb. But Forsberg, the idea’s originator, was neither timid nor lacking in strategic vision. Indeed, her eyes were fixed well beyond banning the bomb. She thought it possible to abolish war altogether. Future generations, she believed, might someday view armed conflict as an outmoded, barbaric practice—something like ritual cannibalism.

A lasting peace on planet Earth? If we don’t assume it’s inconceivable, and thus endeavor to conceive it, how could it plausibly occur?

Forsberg died in 2007 at age sixty-four. Cornell University recently held a conference of peace scholars and other public events to honor her legacy. Its library agreed to host the archives of the organization Forsberg founded in Boston, the Institute for Defense and Disarmament Studies. And Cornell University Press released a book, Toward a Theory of Peace: The Role of Moral Beliefs, based on the MIT dissertation she completed in 1997. Matthew Evangelista and Neta C. Crawford, two of the institute’s former colleagues, have provided a valuable introduction that illuminates Forsberg, weaving together her contributions as activist, analyst, and theorist.

A brilliant, creative public intellectual, Forsberg sought to establish that a permanent worldwide cessation of warfare could conceivably arise over many generations, driven by evolving moral beliefs.

Toward a Theory of Peace conceives of war not as the quintessential instrument of statecraft or an organizing principle of history, but as an example of a larger category of phenomena she terms “socially sanctioned group violence.” This lumps war alongside torture, slavery, the flogging of criminals, and the archaic customs of ritual cannibalism and human sacrifice.

When such violent practices have flourished in human history, Forsberg argues, societies have entrenched them in institutions, and individuals adjusted their moral lenses to accommodate specific exceptions to the general norm that violence is taboo.

But conditions change over time. Eventually, for example, powerful kingdoms no longer saw the need for ritual sacrifice. And, after a previously sanctioned form of violence is banned, moral beliefs reinforce the prohibition, so the practice comes to seem abhorrent. This could conceivably happen with regard to war.

“Today we cannot conceive of ‘just slavery,’ in which the ends justify the means,” Forsberg writes. “In future the norm might be that there is no ‘just war,’ that the phrase represents nothing more than an oxymoron. Such a norm could provide a solid basis for believing that once abolished, war will never recur.”

In Forsberg’s vision, an international system that evolved beyond war would pass through stages, including one in which governments accepted a normative prohibition on using armed force for any purpose save self-defense, and military forces were confined to genuine defense of national territories, not offensive power projection.

She believed the development of nuclear weapons helped point the world in this direction. Their invention made it essential that great powers restrain what she called their “centuries-old pattern of attempting to dominate through war as a tool.” To set the stage for nuclear disarmament, in her view, nations needed to disconnect their nuclear arsenals from conventional military postures and war plans.

The 1980s, in retrospect, brought some modest progress toward these visions. The nuclear freeze campaign led to dozens of U.S. state and local ballot propositions; a freeze resolution even passed the House of Representatives in 1983.

These were symbolic victories only, yet they set the stage for Mikhail Gorbachev’s proposed conventional force reductions in Europe; for arms control gains like the 1987 Intermediate Nuclear Forces Treaty; and for Reagan and Gorbachev’s joint declaration that “a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought.”

The current moment resembles the 1980s in some respects. Nuclear warfare dangers have escalated. An arms race is afoot as nuclear powers modernize their forces and threaten to weaponize space. Opportunities exist to enlarge public awareness and engagement around nuclear weapons. Movement organizers have some strategic choices to make.

By any measure, though, the most dynamic disarmament campaign of recent years has been the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, or ICAN. The group spearheaded the effort that delivered the 2017 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, signed by 122 nations, and led to its being awarded that year’s Nobel Peace Prize. The treaty will officially enter into force after fifty signatory states have ratified it; at present, fifteen have done so.

Swiping a page from Forsberg, ICAN sought to reframe the nuclear narrative, decentering the geostrategic and deterrence doctrines that dominate the discourse. Three intergovernmental conferences in 2013-2014 on the humanitarian aspects of nuclear weapons refocused the debate on the cataclysmic impact any nuclear explosion or nuclear war would unleash.

The goal of the treaty is to stigmatize nuclear weapons, by declaring them illegal. That is a profound shift in the bomb’s international legal and political status. It also speaks eloquently to the mounting frustrations of the non-nuclear-armed countries over the flatlining of disarmament deliberations since the Non-Proliferation Treaty was indefinitely extended in 1995.

“Mindsets change, and we reject some things we once considered normal,” says Ray Acheson, a top ICAN organizer and representative on its international steering group. ICAN is emulating the model of recent successful campaigns against landmines and cluster munitions, which brought about international legal prohibitions on both these indiscriminate weapon classes.

All nine nuclear weapon states have vowed to ignore the ban treaty, so the future will determine its degree of success in establishing a global norm. Acheson acknowledges the ICAN campaign has hardly solved the nuclear question, but she suggests the treaty opens “a space in the door, helping make a radically different voice seem credible in the mainstream narrative.”

A young campaigner from Toronto, Acheson began her career at Randy Forsberg’s institute. She feels sure her mentor would approve of the ban treaty, and that as it progresses toward becoming binding international law, its normative effect of stigmatizing the bomb will deepen significantly—in accordance with Forsberg’s theory, which teaches that abhorrence follows abolition.

Roger Kimmel Smith is a freelance wordsmith based in Ithaca, New York. He is a former network coordinator for the NGO Committee on Disarmament at the United Nations.