July

July 1

July 2

July 3

July 4

July 5

July 6

July 7

July 8

July 9

July 10

July 11

July 12

July 13

July 14

July 15

July 16

July 17

July 18

July 19

July 20

July 21

July 22

July 23

July 24

July 25

July 26

July 27

July 28

July 29

July 30

July 31

July 1. On this day in 1656, the first Quakers arrived in America, having come to what would become Boston. The Puritan colony in Boston was well established by the 1650s with strict rules based on its religion. When the Quakers arrived from England in 1656, they were greeted with accusations of witchcraft, arrests, imprisonment, and the demand that they leave Boston on the next ship. An edict imposing heavy fines on ship captains bringing Quakers to Boston was soon passed by the Puritans. Quakers who stood their ground in protest continued to be attacked, beaten, and at least four were executed before a ruling by Prince Charles II banned executions in the New World. As more diverse settlers began arriving in Boston Harbor, the Quakers found enough acceptance to establish a colony of their own in Pennsylvania. The Puritans’ fear, or xenophobia, collided in America with the founding premise of liberty and justice for all. As America grew, so did its diversity. Acceptance of others was a practice greatly contributed to by the Quakers, who also modeled for others the practices of respecting Native Americans, opposing slavery, resisting war, and pursuing peace. The Quakers of Pennsylvania demonstrated for the other colonies the moral, financial, and cultural benefits of practicing peace rather than war. Quakers taught other Americans about the need to abolish slavery and all forms of violence. Many of the best threads running through U.S. history begin with the Quakers steadfastly promoting their viewpoints as radical minorities dissenting from nearly universally accepted doctrines.

July 2. On this day in 1964, U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law. Enslaved people had become U.S. citizens with the right to vote in 1865. Yet, their rights continued to be suppressed throughout the South. Laws passed by individual states to support segregation, and brutal actions by white supremacy groups such as the Ku Klux Klan threatened the freedoms promised to former slaves. In 1957, the U.S. Justice Department created a Civil Rights Commission to investigate these crimes, which went unaddressed by federal law until President John F. Kennedy was moved by the Civil Rights movement to propose a bill in June of 1963 stating: “This nation was founded by men of many nations and backgrounds. It was founded on the principle that all men are created equal, and that the rights of every man are diminished when the rights of one man are threatened.” Kennedy’s assassination five months later left President Johnson to follow through. In his State of the Union address, Johnson pleaded: “Let this session of Congress be known as the session which did more for civil rights than the last hundred sessions combined.” As the bill reached the Senate, heated arguments from the South were met with a 75-day filibuster. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 finally passed by a two-thirds vote. This Act prohibits segregation in all public accommodations, and bans discrimination by employers and labor unions. It also established an Equal Opportunity Employment Commission offering legal assistance to citizens trying to make a living.

July 3. On this date in 1932, The Green Table, an anti-war ballet reflecting the inhumanity and corruption of war, was performed for the first time in Paris at a choreography competition. Written and choreographed by the German dancer, teacher, and choreographer Kurt Jooss (1901-1979), the ballet is modeled on the “dance of death” depicted in medieval German woodcuts. Each of eight scenes dramatizes a different way in which society complies with the call to war. The figure of Death successively seduces politicians, soldiers, a flag bearer, a young girl, a wife, a mother, refugees, and an industrial profiteer, all of whom are brought into Death’s dance on the same terms by which they live their lives. Only the figure of the wife offers a hint of resistance. She turns into a rebellious partisan and murders a soldier returning from the front. For this offense, Death drags her off to be executed by a firing squad. Before the first shots, however, the wife turns toward Death and genuflects. Death in turn gives her a nod of acknowledgement, then looks up into the audience. In a 2017 review of The Green Table, freelance editor Jennifer Zahrt writes that another reviewer at the performance she attended commented, “Death gazed out at us all as if to ask if we understand.” Zahrt responds, “Yes,” as if agreeing that Death’s call to war is always in some way affirmed. It should be observed, however, that modern history offers many instances in which a small fraction of a given population, organized as a non-violent resistance movement, has managed to silence Death’s call for everyone.

July 4. On this date each year, while the United States celebrates its declaration of independence from England in 1776, an unconditionally non-violent activist group headquartered in Yorkshire, England observes its own “Independence from America Day.” Known as the Menwith Hill Accountability Campaign (MHAC), the group’s core purpose since 1992 has been to explore and illuminate the issue of British sovereignty as it relates to U.S. military bases operating in the United Kingdom. The central focus of the MHAC is the Menwith Hill U.S. base in North Yorkshire, established in 1951. Run by the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA), Menwith Hill is the largest U.S. base outside the U.S. for information-gathering and surveillance. Largely by asking questions in parliament and testing British law in court challenges, the MHAC was able to determine that the 1957 formal agreement between the U.S. and UK relating to NSA Menwith Hill was passed without parliamentary scrutiny. MHAC also revealed that activities pursued by the base in support of U.S. global militarism, the U.S. so-called Missile Defense system, and the NSA’s information-gathering efforts had profound implications for civil liberties and electronic surveillance practices that received little public or parliamentary discussion. The declared ultimate aim of MHAC is the total removal of all U.S. military and surveillance bases in the UK. The organization liaises with, and supports, other activist groups around the world that share similar objectives in their own countries. If such efforts are ultimately successful, they would represent a major step toward global demilitarization. The U.S. currently operates some 800 major military bases in more than 80 countries and territories abroad.

July 5. On this date in 1811, Venezuela became the first Spanish American colony to declare its independence. A War of Independence had been fought from April 1810. The First Republic of Venezuela had an independent government and a constitution, but lasted only one year. Venezuela’s masses resisted being governed by the white elite of Caracas and remained loyal to the crown. The famous hero, Simón Bolívar Palacios, was born in Venezuela of a prominent family and armed resistance to the Spanish continued under him. He was acclaimed El Libertador as a Second Republic of Venezuela was declared and Bolivar was given dictatorial powers. He once again overlooked the aspirations of non-white Venezuelans. It also lasted only one year, from 1813-1814. Caracas remained in Spanish control, but in 1819, Bolivar was named president of the Third Republic of Venezuela. In 1821 Caracas was liberated and Gran Colombia was created, now Venezuela and Colombia. Bolivar left, but carried on fighting on the continent and saw his dream of a united Spanish America come to some fruition in the Confederation of the Andes uniting what is now Ecuador, Bolivia, and Peru. Again, the new government proved difficult to control and did not last. People in Venezuela resented the capital Bogota in far-off Colombia, and resisted the Gran Colombia. Bolivar prepared to leave for exile in Europe, but he died at age 47 of tuberculosis in December 1830, before leaving for Europe. As he was dying, the frustrated liberator of northern South America said that “All who served the revolution have plowed the sea.” Such is the futility of war.

July 6. On this date in 1942, thirteen-year-old Anne Frank, her parents and sister moved into an empty back section of an office building in Amsterdam, Holland in which Anne’s father Otto carried on the family banking business. There the Jewish family–native Germans who had sought refuge in Holland following Hitler’s rise in 1933–hid themselves from the Nazis who now occupied the country. During their seclusion, Anne kept a diary detailing the family’s experience which would make her world-famous. When the family was discovered and arrested two years later, Anne and her mother and sister were deported to a German concentration camp, where all three succumbed within months to typhus fever. All this is common knowledge. Fewer Americans, however, know the rest of the story. Documents disclosed in 2007 indicate that Otto Frank’s continuous nine-month effort in 1941 to secure visas that would get his family into the U.S. were foiled by increasingly prejudicial U.S. vetting standards. After President Roosevelt warned that Jewish refugees already in the U.S. could be “spying under compulsion,” an administrative mandate was issued that barred U.S. acceptance of Jewish refugees with close relatives in Europe, based on the far-fetched notion that the Nazis might hold those relatives hostage in order to force the refugees to undertake espionage for Hitler. The response emblemized the folly and tragedy that can result when war-fevered fears over national security take precedence over humane concerns. It not only suggested that the ethereal Anne Frank might be pressed into service as a Nazi spy. It may also have contributed to the avoidable deaths of untold numbers of European Jews.

July 7. On this date in 2005, a series of coordinated terrorist suicide attacks took place in London. Three men detonated homemade bombs separately but simultaneously in their backpacks in the London Underground and a fourth did the same on a bus. Including the four terrorists, fifty-two people of various nationalities died, and seven hundred were injured. Studies have found that 95% of suicide terrorist attacks are motivated by a desire to get a military occupier to end an occupation. These attacks were not exceptions to that rule. The motivation was ending the occupation of Iraq. A year before, on March 11, 2004, Al Qaeda bombs had killed 191 people in Madrid, Spain, just before an election in which one party had ben campaigning against Spain’s participation in the U.S.-led war on Iraq. The people of Spain voted the Socialists into power, and they removed all Spanish troops from Iraq by May. There were no more bombs in Spain. Following the 2005 attack in London, the British government committed to continuing the brutal occupations of Iraq and Afghanistan. Terrorist attacks in London followed in 2007, 2013, 2016, and 2017. Interestingly, in world history a grand total of zero suicide terrorist attacks have been documented to have been driven by resentment of gifts of food, medicine, schools, or clean energy. Reducing suicide attacks can be aided by reducing collective suffering, deprivation, and injustice, and by responding to nonviolent appeals, which generally precede violent acts but are often times ignored. Treating these crimes as crimes, rather than as acts of war can break a vicious cycle.

July 8. On this date in 2014, in a seven-week conflict that became known as the 2014 Gaza War, Israel launched a seven-week air and ground offensive against the Hamas-ruled Gaza Strip. The stated aim of the operation was to stop rocket fire from Gaza into Israel, which had increased after a June kidnapping and murder of three Israeli teenagers by two Hamas militants in the West Bank had triggered an Israeli crackdown. For its part, Hamas sought to generate international pressure on Israel to lift its blockade of the Gaza Strip. When the war ended, however, civilian deaths, injuries, and homelessness were so one-sidedly on the outgunned Gazan side—well over 2000 Gazan civilians died, compared to only five Israelis—that a special session of the international Russell Tribunal on Palestine was called to investigate possible Israeli genocide. The jury had little difficulty concluding that the Israeli pattern of attack, as well as its indiscriminate targeting, amounted to crimes against humanity, since they imposed collective punishment on the entire civilian population. It also rejected the Israeli claim that its actions could be justified as self-defense against the rocket attacks from Gaza, since those attacks constituted acts of resistance by a people who suffered under punishing Israeli control. Nevertheless, the jury declined to call the Israeli actions “genocide,” since that incrimination legally required compelling evidence of an “intent to destroy.” Of course, to the thousands of dead, injured, and homeless Gazans, these conclusions were of little consequence. For them, and for the rest of the world, the only real answer to the misery of war remains its total abolition.

July 9. On this day in 1955, Albert Einstein, Bertrand Russell and seven other scientists warned that a choice must be made between war and human survival. Distinguished scientists the world over, including Max Born of Germany, and French Communist Frederic Joliot-Curie, joined Albert Einstein and Bertrand Russell in an attempt to abolish war. The Manifesto, the last document Einstein signed before his death, read: “In view of the fact that in any future world war nuclear weapons will certainly be employed, and that such weapons threaten the continued existence of mankind, we urge the governments of the world to realize, and to acknowledge publicly, that their purpose cannot be furthered by a world war, and we urge them, consequently, to find peaceful means for the settlement of all matters of dispute between them.” Former U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara expressed his own fear that a nuclear catastrophe was inevitable unless nuclear arsenals were dismantled, noting: “The average U.S. warhead has a destructive power 20 times that of the Hiroshima bomb. Of the 8,000 active or operational U.S. warheads, 2,000 are on hair-trigger alert…The U.S. has never endorsed the policy of ‘no first use,’ not during my seven years as secretary or since. We have been and remain prepared to initiate the use of nuclear weapons–by the decision of one person, the president….the president is prepared to make a decision within 20 minutes that could launch one of the most devastating weapons in the world. To declare war requires an act of Congress, but to launch a nuclear holocaust requires 20 minutes’ deliberation by the president and his advisors.”

July 10. On this date in 1985, the French government bombed and sunk the Greenpeace flagship The Rainbow Warrior, moored at a wharf in Auckland, a major city in New Zealand’s North Island. Pursuing its interest in protecting the environment, Greenpeace had been using the ship to stage another of its nonviolent campaigns against French nuclear testing in the Pacific. New Zealand was strongly supportive of the protests, reflecting its role as a leader in the international anti-nuclear movement. France, on the other hand, saw nuclear testing as essential to its security, and feared mounting international pressure that could possibly force its termination. The French were especially wary of Greenpeace plans to sail the ship from the Auckland wharf and stage still another protest at French Polynesia’s Mururoa Atoll in the southern Pacific. As a flagship, The Rainbow Warrior could lead a flotilla of smaller protest yachts capable of nonviolent tactics the French navy would find difficult to control. The ship was also large enough to carry enough supplies and communications equipment to maintain both a protracted protest and a flow of radio contact with the outside world and reports and photos to international news organizations. To avoid all this, French Secret Service agents had been sent to sink the ship and prevent it from moving on. The action led to a serious deterioration in relations between New Zealand and France and did much to promote an upsurge in New Zealand nationalism. Because Britain and the United States failed to condemn this act of terrorism, it also hardened support within New Zealand for a more independent foreign policy.

July 11. On this date each year, the UN-sponsored World Population Day, established in 1989, focuses attention on such issues relating to population growth as family planning, gender equality, human and environmental health, education, economic equity, and human rights. In addition to these concerns, population experts have also recognized that brisk population growth in poor countries places stress on available resources that can quickly lead to social instability, civil conflict, and war. This is true in significant part because a fast increase in population tends to produce a sizeable majority of people under thirty. When such a population is led by a weak or autocratic government, and falls short both on vital resources and basic education, health, and employment opportunities for young people, it becomes a potential hot spot for civil conflict. The World Bank cites Angola, Sudan, Haiti, Somalia, and Myanmar as extreme examples of “low-income countries under stress.” In all of them, stability is undermined by a population density that taxes available space and resources. Once consumed by civil conflict, such nations find it hard to resume economic development–even if they are rich in natural resources. Most experts warn that countries with high population growth and not enough resources to provide for their people are likely to breed unrest locally. Of course so-called developed countries exporting weapons, wars, death squads, coups, and interventions, rather than humanitarian and environmentalist aid, also fuel violence in poor and overpopulated parts of the globe, some of them no more overpopulated, simply far more impoverished, than is Japan or Germany.

July 12. On this day in 1817 Henry David Thoreau was born. Though perhaps best known for his philosophical transcendentalism—by which, as in Walden, he viewed the manifestations of nature as reflections of spiritual laws—Thoreau was also a nonconformist who believed that moral behavior derives not from obedience to authority but from the individual conscience. This view is elaborated in his long essay Civil Disobedience, which inspired later civil rights advocates such as Martin Luther King and Mahatma Gandhi. The issues which most concerned Thoreau were slavery and the Mexican War. His refusal to pay taxes to support the war in Mexico led to his imprisonment, and his opposition to slavery to writings such as “Slavery in Massachusetts” and “A Plea for Captain John Brown.” Thoreau’s defense of radical abolitionist John Brown ran counter to the widespread condemnation of Brown following his attempt to arm slaves by stealing weapons from the Harper’s Ferry arsenal. The raid had resulted in the death of one U.S. Marine along with thirteen of the rebels. Brown was charged with murder, treason, and inciting a rebellion by enslaved people, and eventually hanged. Thoreau, however, continued to defend Brown, noting that his intentions had been humane and born of an adherence both to conscience and U.S. Constitutional Rights. The Civil War that followed would tragically result in the deaths of some 700,000 people. Thoreau died as the war began in 1861. Yet, many who supported the Union cause, both soldiers and civilians, remained inspired by Thoreau’s view that abolishing slavery was necessary to a nation claiming to recognize humanity, morals, rights, and conscience.

July 13. On this date in 1863, in the midst of the Civil War, the first wartime draft of U.S. civilians spurred four days of riots in New York City that rank among the bloodiest and most destructive in U.S. history. The uprising did not principally reflect moral opposition to the war. A root cause may have been the discontinuation of cotton imports from the South that were used in 40 percent of all goods shipped from the city’s port. Anxieties produced by the resulting job loss were then exacerbated by the President’s Emancipation Proclamation in September 1862. Lincoln’s edict raised fears among working white men that thousands of freed blacks from the South might soon replace them in an already shrunken job market. Prompted by these fears, many whites began to perversely hold African-Americans responsible both for the war and their own uncertain economic future. Passage of a military conscription law in early 1863 that allowed the wealthy to produce a substitute or buy their way out, drove many white working men to riot. Forced to risk their lives for a Union they felt had betrayed them, they gathered by the thousands on July 13th to perpetrate violent acts of resentment on black citizens, homes, and businesses. Estimates of the number of people killed reach 1,200. Though the rioting was ended on July 16 by arriving federal troops, war had once again produced tragic unintended consequences. Yet, better angels would also play a role. New York’s own African-American abolitionist movement slowly rose again from dormancy to advance black equality in the city and change its society for the better.

July 14. On this date in 1789, the people of Paris stormed and dismantled the Bastille, a royal fortress and prison that had come to symbolize the tyranny of the French Bourbon monarchs. Though hungry and paying heavy taxes from which the clergy and nobility were exempt, the peasants and urban laborers marching to the Bastille sought only to confiscate the army’s gun powder stored there for provision of troops the king had decided to station around Paris. When an unexpected pitched battle ensued, however, the marchers freed the prisoners and arrested the prison governor. Those actions mark the symbolic beginning of the French Revolution, a decade of political turmoil that spawned wars and created a Reign of Terror against counter-revolutionaries in which tens of thousands of people, including the king and queen, were executed. In light of those consequences, it can be argued that a more meaningful event in the Revolution’s early unfolding took place on August 4, 1789. On that day the country’s new National Constituent Assembly met and undertook sweeping reforms that effectively ended France’s historical feudalism, with all of its old rules, tax provisions, and privileges favoring the nobility and clergy. For the most part, France’s peasants welcomed the reforms, seeing them as answers to their most pressing grievances. Yet, the Revolution itself would stretch on for ten years, until Napoleon’s seizure of political power in November 1799. By contrast, the August 4 reforms alone display such remarkable willingness on the part of privileged elites to place the peace and welfare of the nation ahead of private interests as to merit world-historical attention.

July 15. On this date in 1834, the Spanish Inquisition, known officially as The Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition, was definitively abolished during the minority reign of Queen Isabel II. The office had been instituted under papal authority in 1478 by the joint Catholic Monarchs of Spain, King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile. Its original purpose was to help consolidate the newly united Spanish kingdom by weeding out heretical or backsliding Jewish or Muslim converts to Catholicism. Brutal and humiliating methods were employed in pursuing both that end and an ever-widening crackdown on religious non-conformity. Over the Inquisition’s 350 years, around 150,000 Jews, Muslims, Protestants and insubordinate Catholic clerics were prosecuted. Of them, 3,000 to 5,000 were executed, largely by burning at the stake. In addition, some 160,000 Jews who refused Christian baptism were expelled from Spain. The Spanish Inquisition will always be remembered as one of history’s most deplorable episodes, yet the potential for the rise of oppressive power remains deeply rooted in every age. The signs of it are always the same: ever-increasing control of the masses for the wealth and benefit of the governing elites; ever-diminishing wealth and freedom for the people; and the use of mendacious, immoral or brutal techniques to keep things that way. When such signs appear in the modern world, they can be met effectively by an opposing political activism that shifts control to a wider citizenry. The people themselves can be trusted best to champion humane objectives that force those who govern them to seek not elitist power, but the common good.

July 16. On this date in 1945 the U.S. successfully tested the world’s first atomic bomb at the Alamogordo bombing range in New Mexico. The bomb was the product of the so-called Manhattan Project, a research and development effort that began in earnest in early 1942, when fears arose that the Germans were developing their own atomic bomb. The U.S. project culminated at a facility in Los Alamos, New Mexico, where the problems of achieving sufficient critical mass to trigger a nuclear explosion and the design of a deliverable bomb were worked out. When the test bomb was detonated in the New Mexico desert, it vaporized the tower on which it sat, sent a searing light 40,000 feet into the air, and generated the destructive power of 15,000 to 20,000 tons of TNT. Less than a month later, on August 9, 1945, a bomb of the same design, called Fat Boy, was dropped on Nagasaki, Japan, killing an estimated 60,000 to 80,000 people. Following World War II, a nuclear arms race developed between the U.S. and the Soviet Union that was ultimately, or at least temporarily, reined in by a series of arms control agreements. Some were subsequently abrogated by U.S. administrations seeking strategic military advantage in global power relations. Few would argue, however, that either the planned or accidental use of ever more powerful nuclear weapons endanger humanity and other species, and that it is imperative to strengthen disarmament agreements between the two major nuclear powers. Organizers of a new treaty banning all nuclear weapons were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2017.

July 17. On this date in 1998, a treaty adopted at a diplomatic conference in Rome, known as the Rome Statute, established the International Criminal Court. The Court’s purpose is to serve as a last resort for trying military and political leaders in any signatory nation on charges of genocide, war crimes, or crimes against humanity. The Rome Statute establishing the Court entered into force on July 1, 2002, having been ratified or signed by more than 150 countries —though not by the U.S., Russia, or China. For its part, the U.S. government has consistently opposed an international court that could hold its military and political leaders to a uniform global standard of justice. The Clinton administration participated actively in negotiating the treaty establishing the Court, but sought initial Security Council screening of cases that would have enabled the U.S. to veto any prosecutions it opposed. As the Court neared implementation in 2001, the Bush administration vigorously opposed it, negotiating bilateral agreements with other countries aimed at ensuring that U.S. nationals would be immune from prosecution. Years after the Court’s implementation, the Trump administration perhaps revealed most clearly why the U.S. government remains opposed to it. In September 2018, the administration ordered the closure of the Palestine Liberation Organization office in Washington and threatened sanctions against the Court if it should pursue investigations into alleged war crimes by the U.S., Israel, or any of its allies. Might this not suggest that U.S. opposition to the International Criminal Court has less to do with defending the principle of national sovereignty than with protecting unfettered freedom to exercise might over right?

July 18. This date marks the annual observance of the United Nations’ Nelson Mandela International Day. Coinciding with Mandela’s birthday, and held in honor of his many contributions to the culture of peace and freedom, the Day was officially declared by the UN in November 2009 and first observed on July 18, 2010. As a human rights lawyer, a prisoner of conscience, and the first democratically elected president of a free South Africa, Nelson Mandela devoted his life to a variety of causes vital to the promotion of democracy and a culture of peace. They include, among others, human rights, promotion of social justice, reconciliation, race relations, and conflict resolution. About Peace, Mandela remarked in a January 2004 speech in New Delhi, India: “Religion, ethnicity, language, social and cultural practices are elements which enrich human civilization, adding to the wealth of our diversity. Why should they be allowed to become a cause of division and violence?” Mandela’s contribution to peace had little to do with strategic efforts to end global militarism; his focus, which no doubt supports that end, was to bring disparate groups together at the local and national levels in a new sense of shared community. The UN encourages those who wish to honor Mandela on his Day to devote 67 minutes of their time—one minute for each of his 67 years of public service—to carrying out a small gesture of solidarity with humanity. Among its suggestions for doing this are these simple measures: Help someone get a job. Walk a lonely dog at a local animal shelter. Befriend someone from a different cultural background.

July 19. On this date in 1881, Sitting Bull, chief of the Sioux Indian tribes of the American Great Plains, surrendered with his followers to the U.S. Army after crossing back into Dakota Territory following four years of exile in Canada. Sitting Bull had led his people across the border to Canada in May 1877, following their participation a year earlier in the Battle of the Little Big Horn. That was the last of the Great Sioux Wars of the 1870s, in which the Plains Indians fought to defend their heritage as fiercely independent buffalo hunters from the White Man’s encroachments. The Sioux had been victorious at Little Big Horn, even killing the celebrated commander of the U.S. Seventh Cavalry, Lieutenant Colonel George Custer. Their triumph, however, prompted the U.S. army to double-down on efforts to force the Plains Indians onto reservations. It was for this reason that Sitting Bull had led his followers to the safety of Canada. After four years, however, the virtual wipe-out of the Plains buffalo, due in part to overzealous commercial hunting, had brought the exiles to the brink of starvation. Coaxed by U.S. and Canadian authorities, many of them headed south to reservations. Eventually, Sitting Bull returned to the United States with only 187 followers, many old or sick. Following two years of detention, the once proud chief was assigned to the Standing Rock reservation in present-day South Dakota. In 1890, he was shot and killed in an arrest scuffle by U.S. and Indian agents who feared he would help lead the growing Ghost Dance movement aimed at restoring the Sioux way of life.

July 20. On this date in 1874, Lieutenant Colonel George Custer led an expeditionary force consisting of more than 1,000 men and horses and cattle of the U.S. Seventh Cavalry into the previously uncharted Black Hills of modern-day South Dakota. The 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty had set aside reservation lands in the Black Hills region of the Dakota Territory for the Sioux Indian tribes of the Northern Great Plains who agreed to settle there, and barred whites from entering. The Custer expedition’s official purpose was to reconnoiter potential sites for military forts in or near the Black Hills that could control the Sioux tribes that had not signed on to the Laramie Treaty. In reality, however, the expedition also sought to find rumored reserves of minerals, lumber, and gold that U.S. leaders were eager to access by flouting the treaty. As it happened, the expedition did in fact discover gold, which drew thousands of miners illegally to the Black Hills. The U.S. effectively abandoned the Laramie Treaty in February 1876, and the ensuing June 25th Battle of the Little Bighorn in south-central Montana resulted in an unexpected Sioux victory. In September, however, the U.S. army, using tactics that prevented the Sioux from returning to the Black Hills, defeated them in the battle of Slim Buttes. The Sioux called this battle “The Fight Where We Lost the Black Hills.” The U.S., however, may itself have suffered a significant moral defeat. In depriving the Sioux of a safe homeland central to their culture, it sanctioned a foreign policy with no humane limits on its ambitions for economic and military domination.

July 21. On this date in 1972, the award-winning standup comedian George Carlin was arrested on charges of disorderly conduct and profanity after performing his famous “Seven Words You Can Never Use on Television” routine at the annual Summerfest music festival in Milwaukee. Carlin had begun his standup career in the late 1950s as a clean-cut comic known for his clever wordplay and his reminiscences of his Irish working-class upbringing in New York. By 1970, however, he had reinvented himself with a beard, long hair, and jeans, and a comic routine that, according to one critic, was steeped in “drugs and bawdy language.” The transformation drew an immediate backlash from nightclub owners and patrons, so Carlin began appearing at coffee houses, folk clubs, and colleges, where a younger, hipper audience embraced his new image and irreverent material. Then came Summerfest 1972, where Carlin learned that his forbidden “Seven Words” were no more welcome on a stage on the Milwaukee lakefront than on television. Over the following decades, however, those same words—with initials s-p-f-c-c-m-t–came to be broadly accepted as a natural part of a standup’s satirical rhetoric. Did the change reflect a coarsening of American culture? Or was it a victory for unfettered free speech that helped the young see through the numbing hypocrisies and depredations of American private and public life? Comedian Lewis Black once offered a view on why his own obscenity-laced comic indignation never seemed to go out of favor. It didn’t hurt, he noted, that the U.S. government and its leaders gave him a constant flow of fresh material to work from.

July 22. On this date in 1756, the pacifist Religious Society of Friends in colonial Pennsylvania, commonly known as the Quakers, established “The Friendly Association for Regaining and Preserving Peace with the Indians by Pacific Measures.” The stage for this action had been set in 1681, when the English nobleman William Penn, an early Quaker and founder of the Province of Pennsylvania, signed a peace treaty with Tammany, the Indian leader of the Delaware Nation. The general outreach to which the Friendly Association aspired was facilitated by the Quakers’ religious beliefs that God can be experienced without the mediation of clergy and that women are spiritually equal to men. Those tenets harmonized with the shamanistic and egalitarian background of Native American culture, making it easier for the Indians to accept the Quakers as missionaries. For the Quakers, the Association was to serve as a shining example to both Indians and other Europeans of how intercultural relations should be conducted. In practice, therefore, unlike other European charities, the Association actually spent its funds on Indian welfare, did not condemn Indian religions, and welcomed Indians into the Quaker meetinghouse for worship. In 1795, the Quakers appointed a committee to introduce Indians to what they felt were the necessary arts of civilization, such as animal husbandry. They also offered moral advice, urging the Seneca, for example, to be sober, clean, punctual, and industrious. They made no effort, however, to convert any Indians to their faith. To this day, the little-known Friendly Association still serves notice that the surest way to build a better world is through peaceful, respectful, and neighborly relations among nations.

July 23. On this date in 2002, British Prime Minister Tony Blair met with senior U.K. government, defense, and intelligence figures at 10 Downing Street, the Prime Minister’s official residence in London, to discuss the looming prospect of a U.S-led war against Iraq. The minutes of that meeting were recorded in a document known as the Downing Street “Memo,” which was published without official authorization in The [London] Sunday Times in May 2005. Proving once more that War Is a Lie, the Memo plainly reveals not only that the U.S. Bush Administration had made up its mind to go to war against Iraq well before it unsuccessfully sought UN authorization to do so, but also that the British had already agreed to participate in the war as military partners. That agreement had been reached in spite of the recognition by British officials that the case for war against Iraq was “thin.” The Bush administration had grounded its case against the Saddam regime on its alleged combined support of terrorism and weapons of mass destruction. But in doing so, the British officials noted, the administration had fixed its intelligence and facts to fit its policy, not the policy to fit its intelligence and facts. The Downing Street Memo did not come to light early enough to head off the Iraq War, but it may well have helped to make future U.S. wars less probable if the U.S. corporate media had done its best to bring it to the public’s attention. Instead, the media did its best to suppress the Memo’s documented evidence of fraud when it was finally published three years later.

July 24. This date in 1893 marks the birth in Negley, Ohio, of the largely forgotten American peace activist Ammon Hennacy. Born to Quaker parents, Hennacy practiced a very personal brand of peace activism. He did not join others in directly attacking the complex system of U.S. militarism that supports war. Instead, in what he dubbed a “One-Man Revolution,” he appealed to the conscience of ordinary people by protesting war, state executions, and other forms of violence often at the risk of arrest or by prolonged fasting. Calling himself a Christian anarchist, Hennacy refused to register for military service in both world wars, serving two years in jail for his resistance to the first—partly in solitary confinement. He also refused to pay income taxes, which would be used in part to support the military. In his autobiography The Book of Ammon, Hennacy implores his fellow Americans to refuse to register for the draft, buy war bonds, make munitions for war, or pay taxes for war. He did not expect political or institutional mechanisms to bring about change. But he apparently did believe that he himself, along with a few other peace-loving, wise, and courageous citizens, could, by the moral example of their words and actions, move a critical mass of their fellow citizens to insist that conflicts at every level be resolved by peaceful means. Hennacy died in 1970, when the Vietnam War was yet far from over. But he may well have looked forward to the day when the era’s iconic peace slogan was no longer fanciful but real: “Suppose they gave a war and nobody came.”

July 25. On this date in 1947, the U.S. Congress passed the National Security Act, which established much of the bureaucratic framework for the making and implementation of the nation’s foreign policy during the Cold War and beyond. The Act had three components: it brought together the Navy Department and War Department under a new Department of Defense; it established the National Security Council, which was charged with preparing brief reports for the President from an increasing flow of diplomatic and intelligence information; and it set up the Central Intelligence Agency, which was charged not only with gathering intelligence from the various military branches and Department of State, but also with conducting covert operations in foreign nations. Since their founding, these agencies have grown steadily in terms of authority, size, budgets, and power. However, both the ends to which those assets have been applied, and the means by which they are maintained, have raised profound moral and ethical questions. The CIA operates in secrecy at the expense of the rule of law and of the possibility of democratic self-governance. The White House wages secret and public wars without Congressional or United Nations or public authorization. The Department of Defense controls a budget that by 2018 was greater than that of at least the next seven highest military-spending nations combined, yet remains the only U.S. government agency never to be audited. The enormous resources wasted on militarism could otherwise be used to help meet the often desperate physical and economic needs of ordinary people in the United States and around the world.

July 26. On this date in 1947, President Harry Truman signed an executive order aimed at ending racial segregation in the U.S. Armed Forces. Truman’s directive was consistent with growing popular support for ending racial segregation, a goal toward which he had hoped to make modest headway through Congressional legislation. When those efforts were stymied by threats of a Southern filibuster, the president accomplished what he could by using his executive powers. His highest priority was desegregation of the military, in no small part because it was the least susceptible to political resistance. African Americans constituted approximately 11 per cent of all registrants liable for military service and a higher proportion of inductees in all branches of the military except the Marine Corps. Nevertheless, staff officers from all branches of the military expressed their resistance to integration, sometimes even publicly. Full integration did not come until the Korean War, when heavy casualties forced segregated units to merge for survival. Even so, desegregation of the armed forces represented only a first step toward racial justice in the United States, which remained incomplete even after the major civil rights legislation of the 1960s. Beyond that, too, still lay the issue of humane relations among the peoples of the world—which, as displayed at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, remained a bridge too far for Harry Truman. Yet, even in a journey of a thousand miles, first steps are needed. It is only by continual progress in seeing the other’s needs as our own that we can one day realize the vision of human brotherhood and sisterhood in a peaceful world.

July 27. On this date in 1825, the U.S. Congress approved the establishment of Indian Territory. This cleared the way for the forced relocation of the so-called Five Civilized Tribes on the “Trail of Tears” to present-day Oklahoma. The Indian Removal Act was signed by President Andrew Jackson in 1830. The five tribes affected were the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole, all coerced unscrupulously to assimilate and live under U.S. law or leave their homelands. Called the Civilized Tribes, they had integrated to various degrees into a westernized culture and, in the case of the Cherokee, developed a written language. The educated competed with white settlers amid great resentment. The Seminoles fought, and were finally paid to relocate. The Creeks were forcefully removed by the military. No treaty was made with the Cherokee, who brought their case through the courts to the U.S. Supreme Court where they lost. There was much political maneuvering on both sides and after six years, the Treaty of New Echota was proclaimed in force by the President. It gave people two years to cross west over the Mississippi to live in the Indian Territory. When they did not move, they were brutally invaded, their homes burned and looted. Seventeen thousand Cherokees were rounded up and herded into a concentration camp, transported in railway cars, then forced to walk. Four thousand died on the “Trail of Tears.” By 1837, the Jackson administration had removed by war and criminal means, 46,000 Native American people, opening 25 million acres of land to racist white settlement and to slavery.

July 28. In 1914, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, starting WWI. After the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Franz Ferdinand, was assassinated along with his wife by a Serbian nationalist in retaliation for ongoing conflicts with his country, World War I began. Growing nationalism, militarism, imperialism, and war alliances across Europe awaited a spark like the assassination. As nations had tried to free themselves from authoritarian rule, the Industrial Revolution had fueled an arms race. Militarization had allowed the Austro-Hungarian Empire to control as many as thirteen nations, and rising imperialism incited even more expansion by growing military powers. As colonization continued, empires began to collide and then to seek out allies. The Ottoman Empire plus Germany and Austria, or the Central Powers, aligned with the Austro-Hungarian Empire, while Serbia was backed by the Allied Powers of Russia, Japan, France, Italy and the British Empire. The United States joined the Allies in 1917, and citizens from every country found themselves suffering and forced to choose a side. Over nine million troops, and countless citizens died before the fall of the German, Russian, Ottoman, and Austro-Hungarian Empires. The war was ended with a vindictive settlement that predictably helped lead to the next world war. Nationalism, militarism, and imperialism continued despite the horrors inflicted on people all over the world. During World War I, protests sparked by the realization of the tragic cost of war were outlawed in various nations, while war propaganda came into its own as a powerful force of social control.

July 29. On this date in 2002, President George W. Bush described an ‘Axis of Evil’ that supposedly sponsored terrorism, in his State of the Union address. The Axis included Iraq, Iran, and North Korea. It was not simply a rhetorical phrase. The U.S. Department of State designates countries which allegedly provide support for international terrorist acts. Strict sanctions are imposed on these countries. Sanctions include, amongst other conditions: a ban on arms-related exports, prohibitions on economic assistance, and financial restrictions including prohibiting any U.S. citizen from engaging in a financial transaction with a terrorist-list government, as well as restriction of entry to the United States. Beyond sanctions, the United States led an aggressive war on Iraq beginning in 2003, and repeatedly threatened similar attacks on Iran and North Korea for many years. Some roots of the axis of evil idea can be found in the publications of the think tank called the Project for the New American Century, one of which stated: “We cannot allow North Korea, Iran, Iraq…to undermine American leadership, intimidate American allies, or threaten the American homeland itself.” The think tank’s website was subsequently taken down. The former executive director of the organization said in 2006 that it had “already done its job,” suggesting that “our view has been adopted.” The disastrous and counterproductive wars of the years following 2001 have many roots in what was tragically a quite influential vision for endless war and aggression — a vision dependent fundamentally on the ridiculous idea that a few small, poor, independent nations constitute an existential threat to the United States.

CORRECTION: THIS SHOULD HAVE BEEN JANUARY, NOT JULY.

July 30. This date, as proclaimed in 2011 by resolution of the UN General Assembly, marks the annual observance of the International Day of Friendship. The resolution recognizes young people as future leaders, and places particular emphasis on involving them in community activities that include different cultures and promote international understanding and respect for diversity. The International Day of Friendship follows on two previous UN resolutions. The Culture of Peace resolution, proclaimed in 1997, recognizes the enormous harm and suffering caused to children through different forms of conflict and violence. It makes the case that these scourges can be best prevented when their root causes are addressed with a view to solving problems. The other precedent for the International Day of Friendship is a 1998 UN resolution proclaiming an International Decade for a Culture of Peace and Non-Violence for the Children of the World. Observed from 2001 through 2010, this resolution proposes that a key to international peace and cooperation is to educate children everywhere on the importance of living in peace and harmony with others. The International Day of Friendship draws on these precedents in promoting the message that friendship between countries, cultures, and individuals can help produce the foundation of trust necessary for international efforts to overcome the many forces of division that undermine personal security, economic development, social harmony, and peace in the modern world. To observe the Day of Friendship, the UN encourages governments, international organizations, and civil society groups to hold events and activities that contribute to efforts by the international community to promote a dialog aimed at achieving global solidarity, mutual understanding, and reconciliation.

July 31. On this day in 1914 Jean Jaurès was assassinated. An ardent humanist and pacifist leader of the French Socialist Party, Jaures strongly opposed war, and spoke out against the imperialism promoting it. Born in 1859, Jaures’ death has been considered by many as another reason for France’s entry into the First World War. His arguments for peaceful solutions to conflict drew tens of thousands to his lectures and writings, and to consider the benefits of a united European resistance to increasing militarization. Jaures was in the process of organizing workers for a unionized protest just before the war began when he was shot and killed while sitting near a window in a Parisian café. His assassin, French nationalist Raoul Villain, was arrested then acquitted in 1919 before fleeing France. Former opponent President Francois Hollande responded to Jaures death by placing a wreath at the café, and acknowledging his lifelong work towards “peace, unity, and the coming together of the republic.” France then entered WWI with the hope of reversing the perceived loss of status as well as territory acquired by Germany following the Franco-Prussian War. Jaures’ words might have inspired a much more rational choice: “What will the future be like, when the billions now thrown away in preparation for war are spent on useful things to increase the well-being of people, on the construction of decent houses for workers, on improving transportation, on reclaiming the land? The fever of imperialism has become a sickness. It is the disease of a badly run society which does not know how to use its energies at home.”

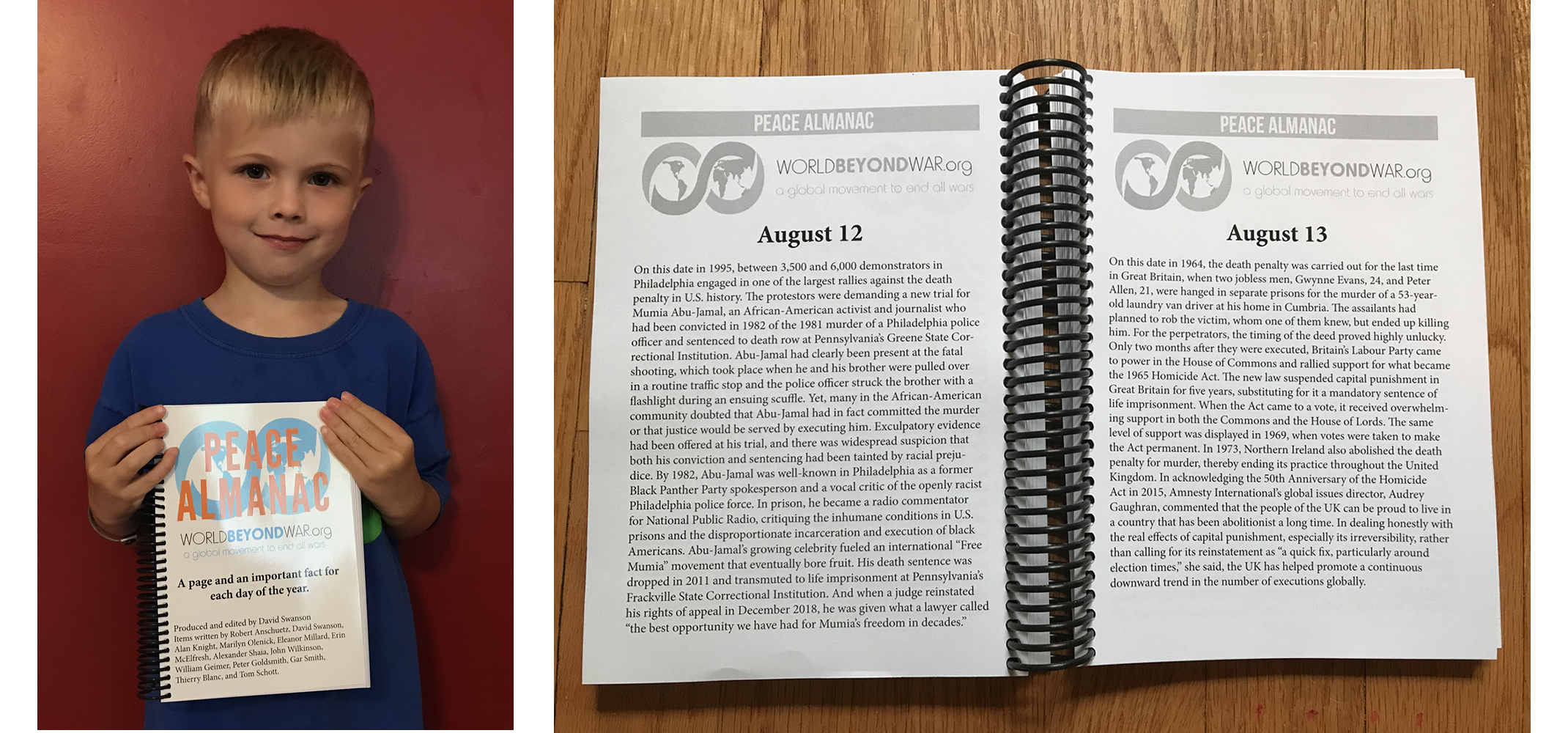

This Peace Almanac lets you know important steps, progress, and setbacks in the movement for peace that have taken place on each day of the year.

Buy the print edition, or the PDF.

This Peace Almanac should remain good for every year until all war is abolished and sustainable peace established. Profits from sales of the print and PDF versions fund the work of World BEYOND War.

Text produced and edited by David Swanson.

Audio recorded by Tim Pluta.

Items written by Robert Anschuetz, David Swanson, Alan Knight, Marilyn Olenick, Eleanor Millard, Erin McElfresh, Alexander Shaia, John Wilkinson, William Geimer, Peter Goldsmith, Gar Smith, Thierry Blanc, and Tom Schott.

Ideas for topics submitted by David Swanson, Robert Anschuetz, Alan Knight, Marilyn Olenick, Eleanor Millard, Darlene Coffman, David McReynolds, Richard Kane, Phil Runkel, Jill Greer, Jim Gould, Bob Stuart, Alaina Huxtable, Thierry Blanc.

Music used by permission from “The End of War,” by Eric Colville.

Audio music and mixing by Sergio Diaz.

Graphics by Parisa Saremi.

World BEYOND War is a global nonviolent movement to end war and establish a just and sustainable peace. We aim to create awareness of popular support for ending war and to further develop that support. We work to advance the idea of not just preventing any particular war but abolishing the entire institution. We strive to replace a culture of war with one of peace in which nonviolent means of conflict resolution take the place of bloodshed.

2 Responses

Hi, Dave–another refreshing drop of healing water in the spectacle of armed hatred!

July 24, Hennacy’s “Suppose they gave a way and nobody came” ever inspires me.” I’ll try to incorporate that on our July 23rd BLM witness.

July 30 there is an opportunity to mention the beginning of AFS International, the grandparent of many teacher-student exchange programs, and starting with the “Armistice Day” declaration after WWI—alluded to but not mentioned in another article. (After many years of friendly effort, and based on the discovery of an old bell in a renewed public building, Jeffersonville, Vermont’s 4th grade, after research, rang the bell on 11-11-11 11 times!) Louise’s Dad, Jesse Freemen Swett, in WWI, at night, sat on the fender of an ambulance, as a “spotter” to pick up live and dead–it was this unit who helped influence the “armistice–Christmas truce—Armistice Day—which disgracefully has been allowed to become another commercial holiday. Again, the Bush’s of the world, preferring $$$ and insensitive pap over truth. Thanks!

another thought came, aligned with one of yours, –at the Montpelier, VT, 7/3 parade, through a series of mishaps, Louise and I carried the “shorter” Will Miller Green Mountain Veterans For Peace, Chapter 57, banner, and I lofted a sign i had used at Black Lives Matter witness, “YOU ARE THE OTHER.” In front of us were “Justice For Palestine” and in back “Hanaford Fife and Drum.” As “Palestine” passed by, one gentleman stepped out from the crowd and held two thumbs down with an angered face. We walked up in front of him, holding the sign—“YOU ARE THE OTHER.” His face turned pensive, and he dropped his hands.