December

December 1

December 2

December 3

December 4

December 5

December 6

December 7

December 8

December 9

December 10

December 11

December 12

December 13

December 14

December 15

December 16

December 17

December 18

December 19

December 20

December 21

December 22

December 23

December 24

December 25

December 26

December 27

December 28

December 29

December 30

December 31

December 1. On this date in 1948 Costa Rica’s president declared the country’s intention to abolish its army. President Jose Figueres Ferrar announced this new national spirit in a speech that day from the nation’s military headquarters, the Cuartel Bellavista, in San Jose. In a symbolic gesture he concluded his speech by smashing a hole in the wall and handing the keys of the facility to the minister of education. Today this former military facility is a national art museum. Ferrar said that, “it is time for Costa Rica to return to her traditional position of having more teachers than soldiers.” Money that had been spent on the military, now is used, not only for education, but health care, cultural endeavors, social services, the natural environment, and a police force providing domestic security. The result is that Costa Ricans have a literacy rate of 96%, a life expectancy of 79.3 years — a world ranking even better than that of the United States — public parks and sanctuaries that protect a quarter of all land, an energy infrastructure based entirely on renewables, and is ranked number 1 by the Happy Planet Index compared to a ranking of 108 by the United States. While most countries surrounding Costa Rica continue to invest in armaments and have been involved in internal civil and cross border conflict, Costa Rica has not. It is a living example that one of the best ways to avoid war is to not prepare for one. Perhaps others of us should join the “Switzerland of Central America” and declare today as they have as “Military Abolition Day.”

December 2. On this date in 1914 Karl Liebknecht cast the only vote against war in the German parliament. Liebknecht had been born in 1871 in Leipzig as the second of five sons. His father was a founding member of the Social Democratic Party (or SPD). When baptized, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels were his baptism sponsors. Liebknecht was married twice, his second wife of Russian origin, and he had three children. In 1897, Liebknecht studied law and economy and graduated with magna cum laude in Berlin. His aim was to defend Marxism. Liebknecht was the leading element in the opposition against WWI. In 1908, while imprisoned for his anti-military writings, he was elected to the Prussian parliament. After voting for the military loan to finance the war in August 1914 – a decision based on loyalty to his party – Liebknecht, on December 2nd, was the only member of the Reichstag to vote against further loans for war. In 1916, he was ousted from the SPD and founded with Rosa Luxemburg and others the Spartacus League which disseminated revolutionary literature. Arrested during an antiwar demonstration, Liebknecht was sentenced for high treason to four years of prison, where he stayed until being pardoned in October 1918. On the 9th of November he declared Freie Sozialistische Republik (Free Socialist Republic) from a balcony of the Berliner Stadtschloss. After a failed and brutally repressed Spartacus uprising with hundreds killed, on the 15th of January Liebknecht and Luxemburg were arrested and executed by members of the SPD. Liebknecht was one of the few politicians who critiqued the human rights abuses in the Ottoman empire.

December 3. On this day in 1997 the treaty banning land mines was signed. This is a good day on which to demand that the remaining few holdout countries sign and ratify it. The Preamble to the Ban states its main purpose: “Determined to put an end to the suffering and casualties caused by anti-personnel mines that kill or maim hundreds of people every week, mostly innocent and defenseless civilians and especially children….” In Ottawa, Canada, representatives from 125 countries met with Canadian Foreign Minister Lloyd Axworthy, and Prime Minister Jean Chretien to sign the treaty banning these weapons whose purpose Chretien described as “for extermination in slow motion.” Landmines from previous wars remained in 69 countries in 1997, continuing the horrors of war. A campaign to end this epidemic was begun six years earlier by the International Committee of the Red Cross, and American human rights leader Jody Williams who founded the International Campaign to Ban Landmines, and was supported by the late Princess Diana of Wales. Militarized countries including the United States and Russia refused to sign the treaty. In response, Foreign Minister Axworthy noted another reason for removing mines was to raise agricultural production in countries such as Afghanistan. Dr. Julius Toth of the international medical assistance group Doctors Without Borders commented “It’s important for those countries to rethink their motives for not signing. If they can justify to the children that I have to deal with when I’m working in the countries with amputees and the victims of these mines…they’d better come up with a pretty valid reason for not being on line.”

December 4. On this date in 1915, Henry Ford set out for Europe from Hoboken, New Jersey on a chartered ocean liner renamed The Peace Ship. Accompanied by 63 peace activists and 54 reporters, his purpose was nothing less than to end the seemingly futile carnage of World War I. As Ford saw it, the stagnant trench warfare served no ends but the death of young men and the profiteering of old ones. Determined to do something about it, he planned to sail to Oslo, Norway and, from there, set out to organize a conference of European neutral nations in The Hague that would convince leaders of the belligerent nations to make peace. On board ship, however, cohesion quickly disintegrated. News of President Wilson’s call to build up the manpower and weaponry of the U.S. army pitted conservative against more radical activists. Then, when the ship arrived in Oslo on December 19, the activists found only a handful of supporters to welcome them. By Christmas Eve, Ford apparently saw the handwriting on the wall and effectively killed the Peace Ship crusade. Claiming illness, he skipped the scheduled train trip to Stockholm and sailed for home on a Norwegian liner. In the end, the peace expedition cost Ford about a half-million dollars and gained him little but ridicule. Yet, it might well be asked whether the foolishness attributed to him was rightly placed. Did it really lie with Ford, who exposed himself to failure in the fight for life? Or with European leaders who sent 11 million soldiers to their deaths in a war with no clear cause or purpose?

December 5. On this date in 1955 the Montgomery Bus Boycott began. The secretary to the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) Rosa Parks, a distinguished citizen of the highly segregated city in Alabama, had refused to give up her bus seat to a white passenger four days before. She was arrested. At least 90 percent of Montgomery’s black citizens stayed off the buses, and the boycott made international news. The boycott was coordinated by the Montgomery Improvement Association and its president, Martin Luther King Jr. This was his “Day of Days.” At a meeting after Mrs. Parks’ arrest, King said, in what would become his familiar speaking style, that they would “work with grim and bold determination to gain justice on the buses,” that if they were wrong, the Supreme Court and the Constitution were wrong, and “If we are wrong, God Almighty is wrong.” Protests and the boycott lasted for 381 days. King was convicted on a charge of interfering with lawful business when carpooling was organized; his home was bombed. The boycott ended with the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that segregation on public buses was unconstitutional. The Montgomery boycott showed that mass non-violent protest could successfully challenge racial segregation and was an example for other southern campaigns that followed. King said, “Christ showed us the way, and Gandhi in India showed it could work.” King went on to help lead many more successful uses of nonviolent action. The boycott is an outstanding example of how nonviolent action can bring about lasting change where violence cannot.

December 6. On this date in 1904 Theodore Roosevelt added to the Monroe Doctrine. The Monroe Doctrine had been articulated by President James Monroe in 1823, in his annual message to Congress. Concerned that Spain might take over its former colonies in South America, with France joining it, he announced that the Western Hemisphere would in effect be protected by the United States, and any European attempt to control any Latin American nation would be considered a hostile act against the United States. Although initially it was a minor statement, this became a cornerstone of U.S. foreign policy, particularly when President Theodore Roosevelt added the Roosevelt Corollary in response to a crisis in Venezuela. This stated that the United States would intervene in conflicts between European countries and Latin American countries to enforce European claims, rather than allowing Europeans to do so directly. Roosevelt claimed the U.S. was justified in being the “international police power” to end conflict. Henceforth, the Monroe Doctrine would be understood as justifying U.S. intervention, rather than merely preventing European intervention in Latin America. This justification was used dozens of times in the next 20 years in the Caribbean and Central America. It was renounced in 1934 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, but it never went away. The Monroe Doctrine has been acted upon continually over the decades, as the United States has assassinated, invaded, facilitated coups, and trained death squads. The Monroe Doctrine is cited to this day by U.S. leaders intent on overthrowing or controlling governments to the south. And it is understood in Latin America as an imperialist claim of superiority and domination.

December 7. On this date in 1941, the Japanese military attacked U.S. bases in the Philippines and in Hawaii at Pearl Harbor. Getting into the war was not a new idea in the Roosevelt White House. FDR had tried lying to the U.S. public about U.S. ships including the Greer and the Kerny, which had been helping British planes track German submarines, but which Roosevelt pretended had been innocently attacked. Roosevelt also lied that he had in his possession a secret Nazi map planning the conquest of South America, as well as a secret Nazi plan for replacing all religions with Nazism. And yet, the people of the United States didn’t buy the idea of going into another war until Pearl Harbor, by which point Roosevelt had already instituted the draft, activated the National Guard, created a huge Navy in two oceans, traded old destroyers to England in exchange for the lease of its bases in the Caribbean and Bermuda, and — just 11 days before the supposedly unexpected attack, and five days before FDR expected it — he had secretly ordered the creation of a list of every Japanese and Japanese-American person in the United States. On August 18th Churchill had told his cabinet, “The President had said he would wage war but not declare it,” and “everything was to be done to force an incident.” Money, planes, trainers, and pilots were provided to China. An economic blockade was imposed on Japan. U.S. military presence was expanded around the Pacific. On November 15th, Army Chief of Staff George Marshall told the media, “We are preparing an offensive war against Japan.”

December 8. On this date in 1941, Congresswoman Jeannette Rankin cast the only vote against U.S. entry into World War II. Jeanette Rankin was born in Montana in 1880, the oldest of seven children. She studied social work in New York and quickly became an organizer for women’s suffrage. Returning to Montana, she continued working for women’s suffrage, and ran for election as a Progressive Republican. In 1916 she became the first and only woman in the House of Representatives. Her first vote in the House was against U.S. entry into World War I. The fact that she was not alone was ignored. She was vilified for supposedly not having the constitution for politics due to her being a woman. Defeated in 1918, she spent the next twenty-two years working for peace organizations and led a simple, self-reliant life. In 1940, at age sixty, she again won election as a Republican. Her lone “no” vote against declaring war on Japan came the day after the bombing of Pearl Harbor which turned the formerly isolationist U.S. public around about entering the war. She later wrote that the imposition of sanctions on Japan in 1940 had been provocative, done in hopes of an attack, a view that is now widely accepted. The public turned against her. Three days later, she withdrew rather than face the vote for war on Germany and Italy. She did not run again for Congress but continued to be a pacifist, travelling to India where she believed that Mahatma Gandhi promised a model for world peace. She actively protested the War on Vietnam. Rankin died at age ninety-three in 1973.

December 9. On this date in 1961 Nazi SS Colonel Adolf Eichmann was found guilty of war crimes during World War II. In 1934 he had been appointed to work in a unit dealing with Jewish affairs. His job had been to help murder Jews and other targets, and he had been responsible for logistics for the “final solution.” He had very efficiently managed the identification, assembly, and transportation of Jews to their destinations at Auschwitz and other extermination camps. He was later called the “architect of the Holocaust.” Although Eichmann was captured by U.S. soldiers at the end of the war, he escaped in 1946 and spent years in the Middle East. In 1958, he and his family settled in Argentina. Israel was concerned about the generation growing up in that new country without direct knowledge of the Holocaust and was anxious to educate them and the rest of the world about it. Israeli secret service agents illegally arrested Eichmann in Argentina in 1960 and took him to Israel for a trial before three special judges. The controversial arrest and four-month trial led to Hannah Arendt’s reporting on what she called the banality of evil. Eichmann denied committing any offenses, saying his office had been responsible only for transport, and that he had been merely a bureaucrat following orders. Eichmann was convicted of war crimes and crimes against humanity. An appeal was denied; he was killed by hanging on June 1, 1962. Adolph Eichmann is an example to the world of the atrocities of racism and war.

December 10. On this date in 1948, the United Nations adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. That made this Human Rights Day. The Declaration was in response to the atrocities of World War II. The UN Commission on Human Rights, chaired by Eleanor Roosevelt, drafted the document over two years. It was the first international statement to use the term “human rights.” The Declaration of Human Rights has 30 articles listing specific civil, political, economic, social, and cultural rights reflecting the values of freedom, dignity, and peace of the United Nations. For instance, it covers the right to life, and the prohibition of slavery and torture, the right to freedom of thought, opinion, religion, conscience, and peaceful association. It was passed with no country against, but abstentions from the USSR, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, Poland, Saudi Arabia, and South Africa. The authoritarian states felt it interfered with their sovereignty, and Soviet ideology placed a premium on economic and social rights while the capitalist West placed more importance on civil and political rights. By way of recognizing economic rights, the Declaration states “Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family.” In the end, the document became non-binding and is looked upon, not as law, but as an expression of morality and as a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations. The rights have been used in treaties, economic agreements, regional human rights law, and constitutions around the world.

December 11. On this date in 1981, the worst massacre in modern Latin American history took place in El Salvador. The killers had been trained and supported by the United States government, which opposed leftist and independent governments under the banner of saving the world from communism. In El Salvador the United States provided an oppressive government with weapons, money, and political support at a cost of one million dollars a day. The operation in remote El Mozote was carried out by the elite Atlacatl battalion which was trained in so-called counter-insurgency at the U.S. Army School of the Americas. The victims were guerrillas and campesinos who had control over much of the countryside. The Atlacatl soldiers systematically interrogated, tortured and executed the men, then took the women, shooting them after raping them, smashing the bellies of pregnant women. They slit the children’s throats, hung them in trees, and burned down the houses. Eight hundred people were slaughtered, many children. A few witnesses escaped. Less than six weeks later, photos of the bodies were published in New York and Washington. The United States knew but did nothing. An amnesty law in El Salvador thwarted investigations in the following years. After seven years of exhumations, in October 2012, over thirty years after El Mozote, the UN Inter-American Court found El Salvador guilty of the massacre, of covering it up, and of failing to investigate afterwards. Compensation for surviving families was minimal. In subsequent years, El Salvador had the world’s highest homicide rate. This is a good day to dedicate time to study and to protest the horrors of current military interventions in other countries.

December 12. On this date in 1982, 30,000 women linked hands to completely encircle the nine-mile perimeter of the U.S.-run military base at Greenham Common in Berkshire, England. Their self-declared purpose was to “embrace the base,” thereby “countering violence with love.” The Greenham Common base, opened in 1942, had been used by both the British Royal Air Force and U.S. Army Air Force during the Second World War. During the ensuing Cold War, it was loaned to the U.S. for use by the U.S. Strategic Air Command. In 1975, the Soviet Union deployed intercontinental ballistic missiles with independently targetable warheads on its territory that the NATO alliance deemed a threat to the security of Western Europe. In response, NATO drew up a plan to deploy more than 500 ground-based nuclear cruise and ballistic missiles in Western Europe by 1983, including 96 cruise missiles at Greenham Common. The earliest women’s demonstration against the NATO plan took place in 1981, when 36 women marched to Greenham Common from Cardiff, Wales. When their hopes to debate the plan with officials were ignored, the women chained themselves to a fence at the air base, set up a Peace Camp there, and began what became an historic 19-year protest against nuclear weapons. With the end of the Cold War, the Greenham Common military base was closed in September 1992. Yet, the enduring demonstration there waged by tens of thousands of women remains significant. In a time of re-heightened nuclear anxieties, it reminds us that life-affirming mass collective protest offers a potent means to point up the life-negating projects of the military/industrial state.

December 13. On this date in 1937 Japanese troops raped and mutilated at least 20,000 Chinese women and girls. Japanese troops captured Nanjing, then the capital of China. Over six weeks they murdered civilians and combatants and looted homes. They raped between 20,000 and 80,000 women and children, cut open pregnant mothers, and sodomized women with bamboo sticks and bayonets. The number of deaths is uncertain, up to 300,000. Documentation was destroyed, and the crime is still a reason for tension between Japan and China. The use of rape and sexual violence as weapons of war has been documented in many armed conflicts including in Bangladesh, Cambodia, Cyprus, Haiti, Liberia, Somalia, Uganda, Bosnia, Herzegovina, and Croatia, as well as in South America. It is often used in ethnic cleansing. In Rwanda, pregnant adolescent girls were ostracized by their families and communities. Some abandoned their babies; others committed suicide. Rape erodes the fabric of a community in a way that few weapons can, and the violation and pain is stamped on entire families. Girls and women are sometimes subjected to forced prostitution and trafficking, or to providing sex in return for provisions, sometimes with the complicity of governments and military authorities. During World War II, women were imprisoned and forced to satisfy occupying forces. Many Asian women were also involved in prostitution during the Vietnam war. Sexual assault presents a major problem in camps for refugees and the displaced. The Nuremberg trials condemned rape as a crime against humanity; governments must be called upon to enforce laws and codes of conduct and to supply counseling and other services for victims.

December 14. On this date in 1962, 1971, 1978, 1979, and 1980, nuclear bomb testing was conducted in the United States, China, and the USSR. This date is a random sample chosen from total known nuclear testing. From 1945 to 2017, there were 2,624 nuclear bomb tests worldwide. The first nuclear bombs were dropped by the United States on Nagasaki and Hiroshima, Japan, in 1945, in what are now seen as early nuclear tests, since no one knew exactly how powerful they would be. Estimates of killed and wounded in Hiroshima are 150,000 and Nagasaki, 75,000. A period of nuclear proliferation followed World War II. During the Cold War, and ever since, the United States and the Soviet Union have vied for supremacy in a global nuclear arms race. The U.S. has conducted 1,054 nuclear tests, followed by the USSR which has conducted 727 tests, and France with 217. Tests have also been done by the UK, Pakistan, North Korea, and India. Israel is also known to possess nuclear weapons, though it has never officially admitted it, and U.S. officials generally go along with that pretense. The strength of nuclear weapons has increased immensely over time, from atomic bombs to thermonuclear hydrogen bombs, and nuclear missiles. Today, nuclear bombs are 3,000 times as powerful as the bomb dropped on Hiroshima. A powerful anti-nuclear movement has led to disarmament agreements and reductions, including the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty of 1970 and the Nuclear Ban Treaty that began collecting ratifications in 2017. Sadly, the nuclear armed nations have not yet supported a ban, and media attention has moved away from their ongoing arms race.

December 15. On this date in 1791 the U.S. Bill of Rights was ratified. In the United States this is Bill of Rights Day. There was much debate over drafting and ratifying the Constitution, which outlines a framework of government, but it finally came into effect in 1789, with an understanding that a Bill of Rights would be added. The Constitution can be amended by ratification by three-fourths of the States. The first ten amendments to the Constitution of the United States are the Bill of Rights, ratified two years after the Constitution was established. One well-known Amendment is the First, which protects the freedoms of speech, press, assembly, and religion. The Second Amendment has evolved into a right to own guns, but originally addressed the right of states to organize militias. Early drafts of the Second Amendment included a ban on a national standing army (also found in the two-year limit on an army contained in the main text of the Constitution). Drafts also included civilian control over the military, and the right to conscientiously object to joining the military. The importance of militias was two-fold: stealing land from Native Americans, and enforcing slavery. The amendment was edited to refer to state militias, rather than a federal militia, at the behest of states that permitted slavery, whose representatives feared both slave revolts and slave emancipation through federal military service. The Third Amendment forbids compelling anyone to host soldiers in their homes, a practice rendered obsolete by hundreds of permanent military bases. The Fourth through Eighth Amendments, like the First, protect people from government abuses, but are routinely violated.

December 16. On this date in 1966 the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) was adopted by the UN General Assembly. It came into force in 1976. As of December 2018, 172 countries had ratified the Covenant. The International Covenant on Economic Social and Cultural Rights, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and the ICCPR are collectively known as the International Bill of Rights. The ICCPR applies to all government entities and agents, and all state and local governments. Article 2 ensures that rights recognized in the ICCPR will be available to everyone in those states that have ratified the Covenant. Article 3 ensures the equal rights of men and women. Among other rights protected by the ICCPR are: the rights to life, to freedom from torture, freedom from slavery, to peaceful assembly, security of the person, freedom of movement, equality before the courts, and a fair trial. Two optional protocols state that anyone has the right to be heard by the Human Rights Committee, and abolish the death penalty. The Human Rights Committee examines reports and addresses its concerns and recommendations to a country. The Committee also publishes General Comments with its interpretations. The American Civil Liberties Union submitted a list of issues in January 2019 to the Committee about violations in the United States, such as: militarization of the U.S.-Mexico border, extraterritorial use of force in targeted killings, National Security Agency surveillance, solitary confinement, and the death penalty. This is a good day to learn more about the ICCPR and to get involved with upholding it.

December 17. On this date in 2010, Mohamed Bouazizi’s self-immolation in Tunisia launched the Arab Spring. Bouazizi was born in 1984 into a poor family with seven children and a sick stepfather. He worked from age ten as a street vendor and quit school to support his family, earning about $140 a month selling produce that he went into debt to purchase. He was well-known, popular, and generous with free produce for the poor. The police harassed him and expected bribes. Reports about his action are conflicting, but his family says the police wanted to see his vendor’s permit, which he didn’t need for selling from a cart. A female official slapped him in the face, spat at him, took his equipment, and insulted his dead father. Her aides beat him. A woman insulting him made his humiliation worse. He tried to see the governor, but was refused. Completely frustrated, he doused himself with gasoline, and set himself alight. Eighteen days later, he died. Along with angry street protests, five thousand people attended his funeral. An investigation ended with the woman official who had insulted him detained. Groups demanded the removal of the regime of the corrupt president, Ben Ali, in power since 1987. Use of force to suppress the protests drew international criticism, and ten days after Bouazizi’s death, Ben Ali was obliged to resign and leave with his family. Protests continued with a new regime. Nonviolent protests known as the Arab Spring spread across the Middle East, with more people marching than at any time in its history. This is a good day to organize nonviolent resistance to injustice.

December 18. On this date in 2011, the United States supposedly ended its war on Iraq, which did not actually end, and which had lasted in one form or another since the year 1990. U.S. President George W. Bush had signed an agreement to have U.S. troops removed from Iraq by 2011, and had begun to remove them in 2008. His successor as president, Barack Obama, had campaigned on ending the war on Iraq and escalating that on Afghanistan. He kept the second half of that promise, tripling U.S. forces in Afghanistan. Obama sought to keep thousands of troops in Iraq beyond the deadline but only if the Iraqi Parliament would grant them immunity for any crimes they might commit. Parliament refused. Obama withdrew most troops, but after his reelection sent thousands of troops back in, despite lacking that criminal immunity. Meanwhile the chaos created by the phase of the war launched in 2003, the 2011 war on Libya, and the arming and supporting of dictators across the region and of rebels in Syria led to more violence and the rise of a group called ISIS that served as an excuse for increased U.S. militarism in Syria and Iraq. The U.S.-led war on Iraq in the years after 2003 killed well over a million Iraqis, according to every serious study undertaken, destroyed basic infrastructure, created disease epidemics, refugee crises, environmental devastation, and effective sociocide, the killing of a society. The United States poured over a trillion dollars into the direct costs of militarism each year for many years following 2001, impoverishing itself in a manner that the September 11th terrorists could only have dreamed of.

December 19. On this date in 1776 Thomas Paine published his first “American Crisis” essay. It begins “These are the times that try men’s souls” and was the first of his 16 pamphlets between 1776 and 1783 during the American Revolution. He had arrived in Pennsylvania from England in 1774, largely uneducated, and written and sold essays defending the idea of a republic. He hated authority in any form, denounced the “tyranny of British rule” and supported the revolution as a just and holy war. He called for theft from Loyalists, advocated their hanging, and praised mob violence against British soldiers. Paine expressed himself in very simple terms, making for ideal wartime propaganda. Rejecting complexity, he said, “I scarcely ever quote; the reason is, I always think.” Some believe that his denouncement of other thinkers reflects his lack of education. He moved back to Great Britain in 1787 but his thought was not accepted. His passionate support of the French Revolution meant he was charged with seditious libel and forced to flee England for France before he could be arrested and stand trial. France fell into anarchy, terror, and war, and Paine was imprisoned during the Terror but eventually was elected to the National Convention in 1792. In 1802, Thomas Jefferson invited Paine back to the United States. Paine held very progressive views on government, labor, economics, and religion — earning himself plenty of enemies. Paine died in New York City in 1809 and is generally listed among the Founding Fathers of the United States. This is a day to read with a critical mind.

December 20. On this date in 1989 the United States attacked Panama. The invasion, under President George H.W. Bush, was called Operation Just Cause, deployed 26,000 troops, and was the largest U.S. war since the war on Vietnam. The stated goals were to restore to the presidency Guillermo Endara, whose election had been financed by ten million U.S. dollars, and who had been deposed by Manual Noriega, and to arrest Noriega on drug trafficking charges. Noriega had been a paid CIA asset for two decades, but his obedience to the United States had been faltering. Motivations for the invasion included maintaining U.S. control of the Panama Canal, maintaining U.S. military bases, gaining support for U.S.-backed fighters in Nicaragua and elsewhere, painting President Bush as a macho leader rather than a wimp, selling weapons, and ending the so-called Vietnam Syndrome, meaning the reluctance of the U.S. public to support more disastrous wars. Up to 4,000 Panamanians died in this “dry run” for the later Gulf War. Panama developed a dollarized economy based on tourism, the service sector, the Panama Canal, retirement gated communities, flagship registry, tax incentives for foreign construction companies and investors, overseas banking, a low cost of living, and a soaring value of land. Panama is known for money laundering, political corruption, and cocaine transhipments. There is widespread unemployment, and the split between the rich and poor wide, with 40% of the population under the poverty level. People live in inadequate housing and have little access to medical care or proper nutrition. This is a good day to think about who gains the spoils of war and who suffers the consequences.

December 21. On this date in 1940, planning for the firebombing of Tokyo by the United States was agreed upon with China. Two weeks shy of a year before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, China’s Minister of Finance T.V. Soong and Colonel Claire Chennault, a retired U.S. Army flier, met in U.S. Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau’s dining room to plan the firebombing of Japan’s capital. The Colonel, who was working for the Chinese, had been urging them to use American pilots to bomb Tokyo since at least 1937. Morgenthau said he could get men released from duty in the U.S. Army Air Corps if the Chinese could pay them $1,000 per month. Soong agreed. The U.S. provided China with planes and trainers, and then pilots. But the firebombing of Tokyo didn’t happen until the night of March 9-10, 1945. Incendiary bombs were used, and the firestorm that raged destroyed 16 square miles of the city, killed an estimated 100,000 people, and left a million people homeless. It was the most destructive bombing in human history, more destructive than Dresden, or even the atomic bombs used on Japan later that year. Where the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki have received much attention and condemnation, the U.S. destruction of more than sixty Japanese cities prior to that bombing has been slight. Bombing cities has been central to U.S. warfare ever since. The result is more casualties but fewer U.S. casualties. This is a good day on which to consider the value of non-U.S. human lives.

December 22. On this date in 1847, Congressman Abraham Lincoln challenged President James K. Polk’s justification for the war on Mexico. Polk had insisted Mexico had started the war by “shedding American blood on American soil.” Lincoln demanded to be shown where fighting had occurred and claimed that U.S. soldiers had invaded a disputed area that was legitimately Mexican. He further criticized Polk for the “sheerest deception” about the origin of the war and for attempting to add to U.S. territory. Lincoln voted against a resolution calling the war justified, and a year later supported one that passed narrowly, declaring the war unconstitutional. The following year the war was concluded with the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo. The treaty forced the Mexican government to agree to the takeover of Alta California and Santa Fe de Nuevo Mexico by the United States. This added 525,000 square miles to U.S. territory, including the land that makes up all or parts of present-day Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming. The United States paid $15 million compensation and cancelled a $3.5 million debt. Mexico acknowledge the loss of Texas and accepted the Rio Grande as its northern border. The greatest territorial expansion of the United States had taken place through Polk’s annexation of Texas in 1845, negotiation of the Oregon Treaty with Great Britain in 1846, and the conclusion of the Mexican-American War. The war was viewed in the U.S. as a victory, but was criticized for human casualties, monetary cost, and heavy-handedness. Lincoln’s opposition to war was no bar to his entering the White House, where, like most presidents, he abandoned it.

December 23. On this date in 1947 President Truman pardoned 1,523 of 15,805 World War II draft resisters. Pardons had always been the prerogative of kings and emperors. In the United States in 1787, at the Constitutional Convention, the pardon power was given to the U.S. President. In 1940, the Selective Training and Service Act was passed. All men between ages 21 and 45 had to register for the draft. After the war, the number of men imprisoned for refusing induction, failing to register, or failing to meet the narrow test for conscientious objection numbered 6,086. The number of desertions was unclear, but in 1944, the Army recorded a rate of 63 desertions for every 1,000 men on active duty. Truman refused to grant an amnesty that would pardon everyone, and instead followed the practice from the First World War: selective pardon. The effect of a pardon would be to restore full civil and political rights. In 1946, Truman named a three-member board to review the cases of conscientious objectors. The board recommended pardons for only 1,523 draft resisters. The board argued that no pardons were justified for those who “set themselves up as wiser and more competent than society to determine their duty to come to the defense of the nation.” In 1948, Eleanor Roosevelt appealed to Truman to review all the cases, but Truman refused, saying the men involved were “just plain cowards or shirkers.” But in 1952, Truman gave pardons to those who had served in the Army in peacetime, and all peacetime deserters from the military.

December 24. On this date in 1924 Costa Rica gave notice to withdraw from the League of Nations to protest the Monroe Doctrine. The Covenant of the League of Nations, adopted upon its formation in 1920, had made reference to such doctrines as a means of assuring “the maintenance of peace” in spite of the fact that most Latin American countries did not view the Monroe Doctrine as doing so. The Monroe Doctrine, created in 1823, had been interpreted to become a tool for protecting U.S. interests in the Americas even if it meant denying sovereign nations their right to self-determination. One of the most significant formal statements re-interpreting the Monroe Doctrine was the Roosevelt Corollary of 1904, which openly sanctioned U.S. imperialism in the Americas. The Roosevelt Corollary explicitly changed the Monroe Doctrine from one of non-intervention by European powers in the Americas to one of active intervention by the United States. Some supporters of this policy believed that it was a part of the “white man’s burden” to act upon the basis of racial, cultural, and religious superiority. Roosevelt had stated that “chronic wrongdoing, or an impotence which results in a general loosening of the ties of a civilized society” gave the U.S. justification to resort to “international police power” in accordance with his interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine. This racist thinking, along with U.S. economic interests, had already paved the way for incursions into Hawaii, Cuba, Panama, the Dominican Republic, Honduras, and Nicaragua by the time Costa Rica made its historic decision in 1924.

December 25. On this date in 1914, in a number of places along the Western Front in World War I, British and German soldiers laid down their arms and climbed from their trenches to exchange holiday greetings and goodwill with the enemy. Though the governments of the warring countries had ignored Pope Benedict XV’s call two weeks earlier to establish a temporary Christmas cease-fire, the soldiers themselves declared an unofficial truce. What prompted them to do it? It may be that, after settling into the drudgery and dangers of trench warfare in northern France, they had begun to identify their own miserable lot with that of the enemy soldiers in trenches not far away. A “live and let-live” attitude had already expressed itself in “bartering and bantering” with the enemy during the “quiet time” between battles. Of course, military officers on both sides were loathe to risk any lessening of zeal for killing the enemy, leading the British by January 1915 to make further informal truces subject to severe punishment. For this reason, the Christmas Truce of 1914 was long thought to be a one-off event. Yet, evidence uncovered in 2010 by German historian Thomas Weber suggests that more localized Christmas truces were also observed in 1915 and 1916. The reason, he believes, is implicit in the fact that, following a battle, surviving soldiers often felt such remorse that they were moved to help injured soldiers on the other side. The soldiers continued to observe a Christmas truce where they could, because their humane instincts, buried in the frenzy of war, remained responsive to the greater possibilities of love and peace.

December 26. On this day in 1872 Norman Angell was born. A love of reading led to his embracing Mill’s Essay on Liberty at the age of 12. He studied in England, France, and Switzerland before migrating to California at 17. He began working for the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, and the San Francisco Chronicle. As a correspondent, he moved to Paris and became sub-editor of the Daily Messenger, then a staff contributor to Éclair. His reporting on the Spanish-American War, the Dreyfus affair, and the Boer War led Angell to his first book, Patriotism under Three Flags: A Plea for Rationalism in Politics (1903). While editing the Paris edition of Lord Northcliffe’s Daily Mail, Angell published another book Europe’s Optical Illusion, which he expanded in 1910 and renamed The Great Illusion. Angell’s theory on war described in his work was that military and political power stood in the way of providing actual defense, and that it is economically impossible for one nation to take over another. The Great Illusion was updated throughout his career, selling over 2 million copies, and was translated into 25 languages. He served as a Labor Member of Parliament, with the World Committee against War and Fascism, on the Executive Committee of the League of Nations Union, and as President of the Abyssinia Association, while publishing forty-one more books, including The Money Game (1928), The Unseen Assassins (1932), The Menace to Our National Defence (1934), Peace with the Dictators? (1938), and After All (1951) on cooperation as the basis for civilization. Angell was knighted in 1931, and received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1933.

December 27. On this date in 1993 Belgrade Women in Black held a New Year protest. Communist Yugoslavia was made up of the republics of Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia, Bosnia, Montenegro and Macedonia. After Prime Minister Tito died in 1980, divisions arose and were encouraged among ethnic groups and nationalists. Slovenia and Croatia declared independence in 1989, sparking conflict with the Yugoslav army. In 1992 war broke out between Bosnia’s Muslims and Croats. A siege of the capital, Sarajevo, took 44 months. 10,000 people died and 20,000 women were raped in ethnic cleansing. Bosnian Serb forces took over Srebrenica and massacred Muslims. NATO bombed Bosnian Serb positions. War broke out in 1998 in Kosovo between Albanian rebels and Serbia, and again NATO began bombing, adding to the death and destruction while claiming to be fighting a so-called humanitarian war. Women in Black formed during these complex and devastating wars. Anti-militarism is their mandate, their “spiritual orientation and political choice.” In the belief that women have always defended their homelands by raising children, supporting the powerless, and working unpaid in the home, they state “We reject military power…the production of arms for the killing of people…the domination of one sex, nation, or state over another.” They organized hundreds of protests during and after the Balkan wars, and are active world-wide with educational workshops and conferences, as well as protests. They create women’s peace groups and have received numerous UN and other women and peace prizes and nominations. This is a good day to look back at wars and ask what might have been done differently.

December 28. On this date in 1991, the government of the Philippines ordered the United States to withdraw from its strategic naval base at Subic Bay. American and Philippine officials had reached tentative agreement the previous summer on a treaty that would have extended the lease of the base for another decade in exchange for $203 million in annual aid. But the treaty was rejected by the Philippine Senate, which assailed the U.S. military presence in the country as a vestige of colonialism and an affront to Philippine sovereignty. The Philippine government then converted Subic Bay into the commercial Subic Freeport Zone, which created some 70,000 new jobs in its first four years. In 2014, however, the U.S. renewed its military presence in the country under terms of the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement. The pact allows the U.S. to build and operate facilities on Philippine bases for use by both countries in enhancing the home country’s ability to defend itself against external threats. Such a need is questionable, however. The Philippines faces no foreseeable danger of invasion, attack, or occupation from anywhere—including from China, which is working with the Philippines to develop resources in the South China Sea under an agreement that precludes U.S. intervention. More broadly, it can be questioned whether the U.S. can at all justify maintaining a military presence in more than 80 countries and territories around the world. Despite the inflated threats cited by politicians and pundits, the U.S. is geographically and strategically well insulated from any real foreign dangers and has no right to incite such dangers elsewhere as self-appointed policeman of the world.

December 29. On this date in 1890, the U.S. military killed 130-300 Sioux men, women, and children in the Wounded Knee Massacre. This was one of the last of many conflicts between the U.S. government and Native American nations during the 19th Century westward expansion of the United States. A religious ceremony known as the Ghost Dance was inspiring resistance, and perceived by the U.S. as threatening a major uprising. The U.S. had recently killed the famous Lakota Chief Sitting Bull in an attempt to arrest him and put an end to the dance. Some Lakota believed the dance would restore their old world and that wearing so-called “ghost shirts” would protect them from being shot. The Lakota, defeated and hungry, were heading for the Pine Ridge reservation. They were stopped by the U.S. 7th Cavalry, taken to Wounded Knee Creek, and surrounded by large rapid-fire guns. The story is that a shot was fired, whether by a Lakota or by a U.S. soldier is unknown. A tragic and avoidable massacre ensued. The number of dead Lakota is disputed, but it is clear that at least half of those killed were women and children. This was the last fight between federal troops and the Sioux until 1973, when members of the American Indian Movement occupied Wounded Knee for 71 days to protest conditions on the reservation. In 1977, Leonard Peltier was convicted of killing two FBI agents there. The U.S. Congress passed a resolution expressing regret for the 1890 massacre a hundred years later, but the United States largely ignores its origins in genocidal policies of war and ethnic cleansing.

December 30. On this date in 1952 Tuskegee Institute reported that 1952 was the first year in 71 years of record keeping that no one was lynched in the U.S.—a dubious recognition that would not stand the test of time. (The last lynching in the U.S. occurred in the 21st century.) The cold statistic could hardly convey the horror of the worldwide phenomenon of the extrajudicial murder of people. Commonly committed by frenzied mobs, lynching provides a graphic example of humankind’s almost universal credo to distrust and fear the “other,” the “different.” Lynching stands as a stark illustration in miniature of the taproots of almost all war in human history, which have always featured conflict between people of different nationalities, religions, races, political systems, or philosophies. Although hardly unknown elsewhere in the world, lynching in the United States, which flourished from the post-Civil War years well into the 20th century, was characteristically a race-motivated crime. Over 73 percent of the almost 4,800 lynching victims in the U.S. were African-American. Lynchings were largely—though not exclusively—a Southern phenomenon. Indeed, a mere 12 southern states accounted for the 4,075 lynchings of African-Americans from 1877 to 1950. Ninety-nine percent of the people who carried out these crimes were never punished by either state or local officials. Nothing could be more illustrative of the current human inability to cooperate in preventing global catastrophes, such as destruction of the environment or global nuclear war than the fact that the United States Congress failed to pass a law declaring lynching a federal crime until December, 2018, after 100 years of trying.

December 31. On this date, many people around the world celebrate the end of a year and the beginning of a new one. Often, people create resolutions or commitments to meet particular goals in the year just beginning. World BEYOND War has created a Declaration of Peace that we believe also serves as an excellent new year’s resolution. This Declaration of Peace or peace pledge is found online at worldbeyondwar.org and has been signed by many thousands of individuals and organizations in almost every corner of the world. The Declaration consists of only two sentences, and reads in its entirety: “I understand that wars and militarism make us less safe rather than protect us, that they kill, injure and traumatize adults, children and infants, severely damage the natural environment, erode civil liberties, and drain our economies, siphoning resources from life-affirming activities. I commit to engage in and support nonviolent efforts to end all war and preparations for war and to create a sustainable and just peace.” For anyone who has any doubts about any portions of the declaration — Is it really true that wars endanger us? Does militarism really damage the natural environment? Isn’t war inevitable or necessary or beneficial? — World BEYOND War has created a whole website to answer such questions. At worldbeyondwar.org are lists and explanations of myths believed about war and reasons why we need to end war, as well as campaigns one can get involved in to advance that goal. Don’t sign the peace pledge unless you mean it. But please do mean it! See worldbeyondwar.org Happy New Year!

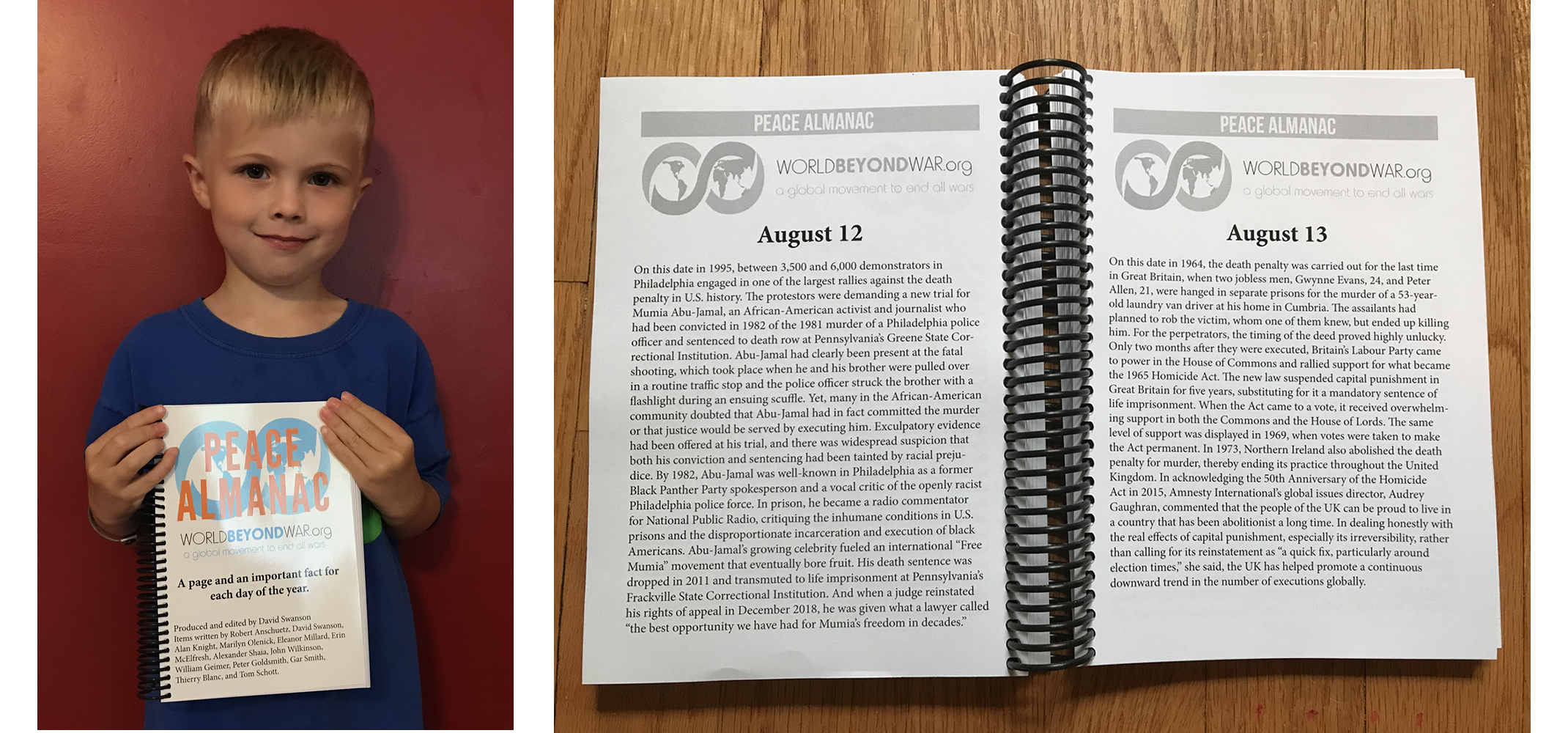

This Peace Almanac lets you know important steps, progress, and setbacks in the movement for peace that have taken place on each day of the year.

Buy the print edition, or the PDF.

This Peace Almanac should remain good for every year until all war is abolished and sustainable peace established. Profits from sales of the print and PDF versions fund the work of World BEYOND War.

Text produced and edited by David Swanson.

Audio recorded by Tim Pluta.

Items written by Robert Anschuetz, David Swanson, Alan Knight, Marilyn Olenick, Eleanor Millard, Erin McElfresh, Alexander Shaia, John Wilkinson, William Geimer, Peter Goldsmith, Gar Smith, Thierry Blanc, and Tom Schott.

Ideas for topics submitted by David Swanson, Robert Anschuetz, Alan Knight, Marilyn Olenick, Eleanor Millard, Darlene Coffman, David McReynolds, Richard Kane, Phil Runkel, Jill Greer, Jim Gould, Bob Stuart, Alaina Huxtable, Thierry Blanc.

Music used by permission from “The End of War,” by Eric Colville.

Audio music and mixing by Sergio Diaz.

Graphics by Parisa Saremi.

World BEYOND War is a global nonviolent movement to end war and establish a just and sustainable peace. We aim to create awareness of popular support for ending war and to further develop that support. We work to advance the idea of not just preventing any particular war but abolishing the entire institution. We strive to replace a culture of war with one of peace in which nonviolent means of conflict resolution take the place of bloodshed.