By C Liegh McInnis, World BEYOND War, May 5, 2023

Presented during the May 4, 2023, Vietnam to Ukraine: Lessons for the US Peace Movement Remembering Kent State and Jackson State! Webinar hosted by the Green Party Peace Action Committee; Peoples Network for Planet, Justice & Peace; and Green Party of Ohio

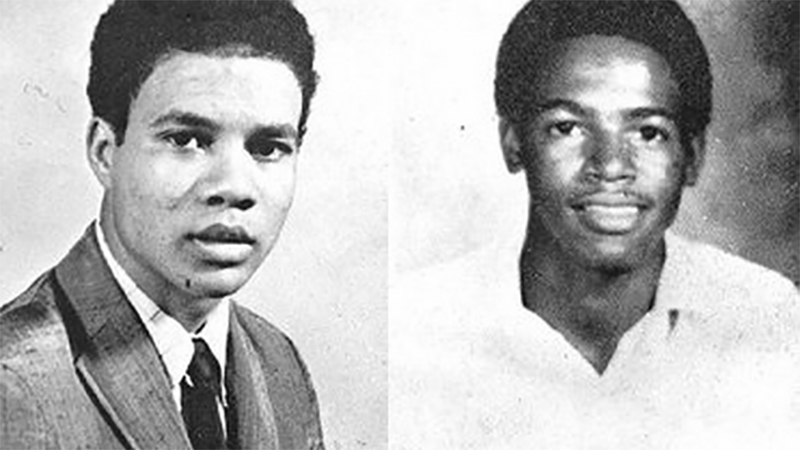

Jackson State University, like most HBCUs, is the epitome of the black struggle against colonialism. While the vast majority of HBCUs are established during or just after Reconstruction, they are mired in the American colonial system of segregating and underfunding black people and black institutions so that they never become more than de facto plantations in which white oppressors control the curriculum to control the intellectual aptitude and economic progress of African Americans. One example of this is that, well into the late 1970s, Mississippi’s three public HBCUs—Jackson State, Alcorn, and Mississippi Valley—had to get approval from the state College Board just to invite speakers to the campus. In most aspects, Jackson State didn’t have the autonomy to decide its educational direction. However, thanks to great leaders and professors, such as former President Dr. John A. Peoples, poet and novelist Dr. Margaret Walker Alexander, and others, Jackson State was able to circumvent Mississippi’s educational Apartheid and become one of only eleven HBCUs to achieve Research Two status. In fact, Jackson State is the second oldest Research Two HBCU. Additionally, Jackson State was part of what some call the Civil Rights Triangle as JSU, the COFO Building, and Medgar Evers’ office as head of the Mississippi NAACP were all on the same street, diagonal from each other, forming a triangle. So, just off the campus of JSU, is the COFO Building, which served as the headquarters for Freedom Summer and attracted many JSU students as volunteers. And, of course, many JSU students were part of the NAACP youth branch because Evers was instrumental in organizing them into the Movement. But, as y’all can imagine, this didn’t sit well with the majority white College Board or the majority white state legislature, which led to additional cuts in funding and general harassment of students and teachers that culminated into the 1970 shooting in which the Mississippi National Guard surrounded the campus and the Mississippi Highway Patrol and Jackson Police Department marched onto the campus, firing over four hundred rounds into a female dormitory, injuring eighteen and killing two: Phillip Lafayette Gibbs and James Earl Green.

Connecting this event to tonight’s discussion, it’s important to understand that the Jackson State student movement included several Vietnam veterans, such as my father, Claude McInnis, who had returned home and enrolled in college, determined to make the country uphold its democratic creed for which they were erroneously fighting in foreign lands. Similarly, my father and I were both forced to choose between the lesser colonizing evils. He was not drafted into Vietnam. My father was forced into military service because a white sheriff came to my grandfather’s home and presented an ultimatum, “If that li’l red nigger son of yours is here much longer, he’s gon’ find himself real familiar with a tree.” As such, my grandfather enlisted my father into the army because he felt that Vietnam would be safer than Mississippi because, at least in Vietnam, he would have a weapon to defend himself. Twenty-two years later, I found myself having to enlist into the Mississippi National Guard—the same force that participated in the massacre at JSU—because I had no other way to finish my college education. This is a continued pattern of black people having to choose between the lesser of two evils simply to survive. Yet, my father taught me that, at some point, life cannot be just about choosing between the lesser of two evils and that one must be willing to sacrifice everything to create a world in which people have real choices that can lead to full citizenship that enables them to fulfill the potential of their humanity. That’s what he did by co-founding the Vet Club, which was an organization of Vietnam Vets who worked with other local civil rights and Black Nationalist organizations to aid in the liberation of African peoples from white tyranny. This included patrolling the street that ran through the JSU campus to ensure that white motorists would obey the speed limit because students were often harassed by them with two students being struck by white motorists and no charges ever being filed. But, I want to be clear. On the night of the May 15, 1970, shooting, nothing was happening on the campus that would have warranted the presence of law enforcement. There was no rally or any type of political action by the students. The only rioting was the local law enforcement rioting against innocent black students. That shooting was an unmitigated attack on Jackson State as the symbol of black people using education to become sovereign beings. And the presence of unnecessary law enforcement on the Jackson State campus is no different from the presence of unnecessary military forces in Vietnam and anywhere else our forces have been deployed solely to establish or maintain America’s colonial regime.

Continuing the work of my father and other Mississippi Veterans of the Civil Rights Movement, I have worked in three ways to illuminate this history, teach this history, and use this history to inspire others to become active in resisting oppression in all forms. As a creative writer, I have published poems and short stories about the 1970 attack on JSU by local law enforcement and the general history and struggle of Jackson State. As an essayist, I have published articles about the causes and aftermath of the 1970 attack on JSU and the continued struggle of the institution against white supremacist policies. As a teacher at JSU, one of the prompts for my composition literature class’ cause and effect paper was “What was the cause of the 1970 attack on Jackson state?” So, many of my students got to research and write about this history. And, finally, as a teacher, I was active in and testified during the federal proceedings of the Ayers Case in which Mississippi’s three public HBCUs sued the state for its discriminatory funding practices. In all of my work, especially as a creative writer, the Vietnam era and the US Peace Movement have taught me four things. One—silence is the friend of evil. Two—local, national, and international politics are collaborative if not one and same, especially as it relates to the government funding wars to expand its empire rather than funding education, health, and employment initiatives to provide equality to its own citizens. Three—there is no way that a government can engage or execute unjust actions at home or abroad and be deemed a just entity. And, four—only when the people remember that they are the government and that elected officials work for them will we be able to elect representatives and establish policies that nurture peace rather than colonialism. I use these lessons as a guide to my writing and teaching to ensure that my work can provide information and inspiration for others to help build a more peaceful and productive world. And, I thank you for having me.

McInnis is a poet, short story writer, and retired instructor of English at Jackson State University, the former editor/publisher of Black Magnolias Literary Journal, and the author of eight books, including four collections of poetry, one collection of short fiction (Scripts: Sketches and Tales of Urban Mississippi), one work of literary criticism (The Lyrics of Prince: A Literary Look at a Creative, Musical Poet, Philosopher, and Storyteller), one co- authored work, Brother Hollis: The Sankofa of a Movement Man, which discusses the life of a Mississippi Civil Rights icon, and the former First Runner-Up of the Amiri Baraka/Sonia Sanchez Poetry Award sponsored by North Carolina State A&T. Additionally, his work has been published in numerous journals and anthologies, including Obsidian, Tribes, Konch, Down to the Dark River, an anthology of poems about the Mississippi River, and Black Hollywood Unchained, which is an anthology of essays about Hollywood’s portrayal of African Americans.