I just crossed this off my list of areas to see in Europe.

From Edward Morris, March 20, 2018.

When you picture France, you probably think of a lush countryside or the romantic “City of Lights” (Paris). However, France didn’t always seem that way, and during the horrors of World War I, it had a much bleaker landscape.

That’s because, deep within its borders, there lies a 460-square-mile section known as Zone Rouge (“Red Zone”), which has been forbidden from public use for nearly a century. When you see what’s hiding within this dangerous place, you may never look at France the same way again.

In World War I, near the French town of Verdun, 460 square miles of forest became the site of one of the bloodiest battles in recorded history. The Battle of Verdun lasted for 303 days and killed 70,000 soldiers per month.

Today, the area is considered extremely dangerous because of all the unexploded munitions in the ground. Experts say that it would take 300 to 700 years to clean the area, though it may even be impossible, due to the amount of toxins absorbed by the soil.

The area is fenced off from public use.

There were so many unused, dangerous weapons and human remains in the area that the government determined they had to completely relocate everyone living in the area. There were whole towns that were evacuated and wiped off the map after being deemed “casualties of war.”

You wouldn’t be able to tell from looking at it now, but much of this land was once inhabited.

“Here stood the church,” according to one photographer.

This is what a French battlefield looked like shortly after the war.

Forest keepers and hunters still made use of the area until 2004, when German researchers found 17% arsenic in the soil. That’s ten times higher than what most other red zones typically have.

The arsenic levels are 300 times higher than what humans can typically tolerate. The lead levels were also high in many of the animals found in the area, especially the wild boars.

In many parts of the red zone, only 1% of the plant and animal life survives.

I couldn’t imagine swimming in there.

The rockets and other weapons exposed perchlorate to the area, which made the water in the surrounding areas effectively undrinkable.

In 2012, the government officially restricted the public from entering the site after realizing the state that it was in.

Many people doubt that the French government and European Union are doing enough to keep the area safe, which scientists say must be continuously monitored.

See, the French made a special organization called Department du Deminage, which was committed to clearing out as many weapons from the area as possible since its inception in 1946. By the start of the 1970’s, the Department believed that their cleaning efforts were successful.

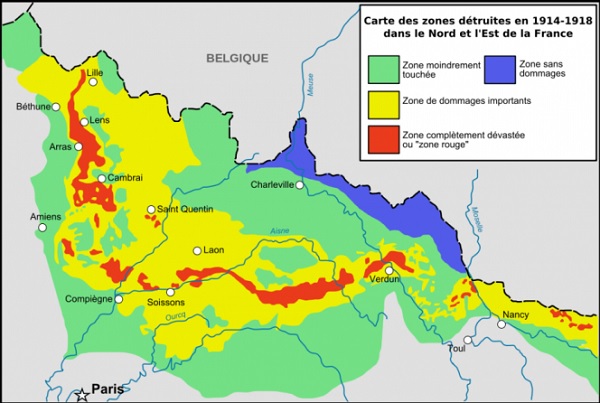

In the map above you can see the zone’s risk levels, the red area being the most dangerous.

When they thought that the task was complete, they opened up more land and roads to the public. However, they didn’t consider the leaks and other consequences of detonating so many chemical bombs. By the time that the area was officially restricted in 2012, hundreds had died from remaining munitions.

Now they know that for at least 10,000 more years, nonbiodegradable lead, zinc, and mercury will contaminate the soil with the remaining shrapnel.

In 1916, the Battle of Verdun claimed over 300,000 lives in the Red Zone. It seems unfathomable that the violence would continue after the war, but explosives are still in the soil, and injuries and deaths still occur in the area today as a result. Even the people who try to remove the munitions often suffer casualties.

The relatively less dangerous yellow and blue zones still get hit with shells every year.

If officials keep going at the pace they are now, authorities say that it could take anywhere between 300-700 years to complete clearing the area of dangerous remnants from the war.

Families in the surrounding areas obviously can’t use the quarantined areas, so they have to make do with what they can. This restaurant called “Le Tommy” in the town of Pozières is actually a repurposed trench.

Some memorials in the zone have been opened to the public, dedicated to those who “died for France.”

Many people living in the surrounding areas have personal collections of remains, with some even opening small museums.

Zone Rouge serves as a reminder that the horrors of war do not necessarily end when the war does.

War doesn’t come and go quietly. All we can do is remember what happened, learn from our mistakes, and try to clean up the mess that we made.

2 Responses

Super, tank you

Super ,muszę zwiedzić te miejsca .