By Sam Husseini, August 30, 2018

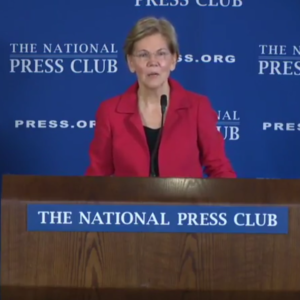

On Tuesday, Sen. Elizabeth Warren addressed the National Press Club, outlining with great specificity a host of proposals on issues including eliminating financial conflicts, close the revolving door between business and government and, perhaps most notably, reforming corporate structures.

On Tuesday, Sen. Elizabeth Warren addressed the National Press Club, outlining with great specificity a host of proposals on issues including eliminating financial conflicts, close the revolving door between business and government and, perhaps most notably, reforming corporate structures.

Warren gave a blistering attack on corporate power run amok, giving example after example, like Congressman Billy Tauzin doing the pharmaceutical lobby’s bidding by preventing a bill for expanded Medicare coverage from allowing the program to negotiate lower drug prices. Noted Warren: “In December of 2003, the very same month the bill was signed into law, PhRMA — the drug companies’ biggest lobbying group — dangled the possibility that Billy could be their next CEO.

“In February of 2004, Congressman Tauzin announced that he wouldn’t seek re-election. Ten months later, he became CEO of PhRMA — at an annual salary of $2 million. Big Pharma certainly knows how to say ‘thank you for your service.'”

But I found that Warren’s tenacity when ripping things like corporate lobbyists’ “pre-bribes” suddenly evaporated when dealing with issues like the enormous military budget and Israeli assaults on Palestinian children.

The Press Club moderator, Angela Greiling Keane, early in the news conference asked about Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s keeping press out of town hall meetings, pairing that with Trump’s outright attacks on media.

Husseini: Sam Husseini with The Nation and the Institute for Public Accuracy. Cortez, who was mentioned earlier, and other likely incoming congressional members next year propose slashing the military budget to help pay for human and environmental needs. Do you agree? And if I could, a second question: would you consider introducing and sponsoring [a version of] Betty McCollum’s bill on Palestinians children’s rights in the Senate?Warren: I now sit on Armed Services and I have been in the middle of the sausage making factory on that one. And that has pushed me even more strongly in the direction of systemic reforms. I want to be able to have those debates. I want to be able to get them out in the open and talk about these poor issues that affect our government, affect our people. I want to be able to debate them on the floor of the senate. I want to be able to do amendments on them. Right now the whole of big money over our government stops much of that. It chokes off much of the debate we should have. So I am going to give you a system-wide answer because I think that’s what matters here. This is not about one particular proposal, this is all the way across. How is it that we get the voices of the people heard in government instead of over and over the voices of the wealthy and the well connected. The voices of those with higher armies of lobbyists. So for me that’s what this is about.

But part of the power that the wealthy and well connected have is getting direct responses to their specific concerns. Political funders are unlikely impressed with broad “system-wide answers”.

In a sense, her non-response to very direct questions rather highlighted the problem she is presumably addressing.

And we’ve been here before.

Bernie Sanders, in his 2016 presidential run, was remarkably vague or even outright repressive regarding foreign policy, especially early on. This reach almost comical proportions when during a debate on CBS just after the November 2015 bombing in Paris, he tried to avoid substantially addressing the issue, wanting instead to fall back on income inequality. Certainly, Sanders was arguably treated very unfairly by the Democratic Party and media establishment, but he was greatly diminished by not having serious foreign policy answers.

Warren and other “progressive” candidates may be set to repeat that. Sanders did address foreign policy more at the end of the campaign and since, but his answers are still problematic at times and at best it was all too little too late.

One question is, realistically, what are Warren’s goals here? It could well be a good faith effort by someone committed to changing the world for the better. But then, why the selectivity?

If it was enactment of these policies, then the strongest way to do that might have been to find a rogue Republican to pair up with on at least some aspects of her proposals so as to avoid charges being purely politically motivated. When questioned by a New York Post reporter at the news conference, Warren couldn’t name a Republican whom she might work with. This would especially be the case since Trump — like Obama before him — ran against the establishment.

Is it to make her a leading contender for the Democratic nomination? If so, the hope would be that she’s not simply playing the role of what Bruce Dixon of Black Agenda Report calls “sheepdogging” — that is, the presidential run or promise of a run by a Sanders or Warren as simply a tool the Democratic Party establishment uses to keep enough of the public “on the reservation”.

Said Warren of her own financial reform proposals: “Inside Washington, some of these proposals will be very unpopular, even with some of my friends. Outside Washington, I expect that most people will see these ideas as no-brainers and be shocked they’re not already the law.

Why doesn’t the same principle apply to funding perpetual wars and massive human rights abuses against children?