By Richard Tanter, Pearls and Irritations, July25, 2023

What do the governments of other US allies, including Hungary, Norway, the Philippines, and the former puppet government of Afghanistan, possess that Australian governments do not? The answer is a conception of genuine sovereignty, and obligations to transparency that are foreign to Australian governments, particularly the incumbent Albanese government.

In November 2011, Prime Minister Julia Gillard and President Barack Obama announced plans for annual deployment of a US Marine Rotational Force to Darwin and US Air Force aircraft to Australian bases in the Northern Territory, commencing in April 2012.

The United States – Australia Force Posture Agreement signed on 12 August 2014 formalised a much larger strategic upgrade of alliance arrangements initiated by the two leaders. Over the past decade both governments have made very large budgetary commitments to infrastructure developments at Australian defence facilities in northern Australia under various headings, including the Australian Defence Department’s continually evolving United States Force Posture Initiative.

A key feature of the Force Posture Agreement is the concept of ‘Agreed Facilities and Areas’, defined in Article I of the Agreement as follows:

‘“Agreed Facilities and Areas” means the facilities and areas in the territory of Australia provided by Australia which may be listed in Annex A appended to this Agreement, and such other facilities and areas in the territory of Australia as may be provided by Australia in the future, to which United States Forces, United States Contractors, dependants, and other United States Government personnel as mutually agreed, shall have the right to access and use pursuant to this Agreement.’

Yet, in the nine years following the signing of the Force Posture Agreement in 2014 no version of Annex A of the Agreement has been made public, and no official statements appear to have explicitly identified any given ADF facility as an Agreed Facility or Area under the terms of the 2014 FPA. The Defence Department website ‘United States Force Posture Initiatives’ provides a number of source materials about different aspects of the Initiatives. But none of these documents contain or point to any information about which Australian defence facilities are Agreed Facilities and Areas to which, under the FPA, US forces are entitled to access.

Perhaps the best known example to date of the impact of the Force Posture Agreement has been the huge upgrade of RAAF Base Tindal near Katherine, involving a more than A$1.5 billion expansion financed by Australia and a US$360 million investment to facilitate rotational deployment of USAF B-52H strategic bombers, plus infrastructure to accommodate the fleets of US and Australian logistics supply aircraft, refuelling tankers, protective fighters, and airborne early warning and control aircraft – and their permanent operating personnel – to accompany the B-52s on offensive missions headed for China.

A simple question ought to be: to which Australian defence bases do United States Forces and contractors have access under the Force Posture Agreement?

From construction announcements by the Australian, Northern Territory and United States governments it is possible to construct a rough first list of Force Posture Initiative infrastructure projects, at least for northern Australia, in three categories:

Northern Territory Training Areas and Ranges Upgrades Project

Robertson Barracks Close Training Area,

Kangaroo Flats Training Area,

Mount Bundey Training Area

Bradshaw Field Training Area

RAAF bases expansion

RAAF Base Darwin

RAAF Base Tindal

U.S. Bulk Liquid Storage Facility, East Arm, Darwin

Defence Logistics Agency / Crowley Solutions

It has to be stressed that this is very much a preliminary list, with announcements in 2021 indicating planned expansion and upgrading for three further sets of ‘Enhanced Cooperation’ beyond the Marine Rotational Force and the US Air Force, to include ground forces, maritime forces, and logistics, sustainment and maintenance facilities. Each signals novel or expanded access by US forces and contractors to ADF facilities.

In December 2022 the Australia-United States ministerial group of defence and foreign ministers announced plans for upgrading RAAF and other ADF ‘bare bases’ in northern Australia as a contribution to US Air Force planning to geographically diversify logistics and fuel facilities to complicate Chinese strike planning.

‘Collaborative facilities’

This great flurry of highly visible, expensive, and strategically significant infrastructure planning portends a lengthening list of Australian defence facilities with greater levels of US access than ever before since 1945. The Albanese government signalled its thinking on this issue starting with its reaffirmation of support for the well-known ‘joint facilities’ – most notably the giant intelligence base known as the ‘truly joint in nature’ Joint Defence Facility Pine Gap outside Alice Springs, the USAF-operated seismic nuclear detonation station also in Alice Springs, and the tiny but militarily important USAF/BOM-operated Learmonth Solar Observatory on the Exmouth Peninsula south of North West Cape. Each of these are the subject of longstanding (from the 1950s and 1960s) individual agreements antedating the FPI.

However, in a ministerial statement on 9 February this year, Defence Minister Richard Marles announced a new category of bases to which US forces have access, under the possibly unfortunately-named heading of ‘collaborative facilities’.

According to Marles

‘We also collaborate through Australian owned and controlled facilities, such as the Harold E Holt Naval Communication Station and the Australian Defence Satellite Communication Station.’

Whatever else Marles may have meant here, the reference to North West Cape was a little opaque. Australia’s most dense network of high technology facilities on the Exmouth Peninsula is now home to not only the very low frequency submarine communications station at North West Cape established in the 1960s, but also to the new Space Surveillance Telescope and Space Surveillance Radar, indeed jointly operated by both militaries, feeding their data on orbiting adversary satellites to Combined Space Command in the US in preparation for the military struggle for ‘primacy’ in space.

Each of these ‘joint-ish’ facilities on the Exmouth Peninsula, like the US communications facilities constructed around the same time adjoining the Australian Defence Satellite Communication Station signals interception base further south at Kojarena near Geraldton, have their own sets of bilateral agreements – presumably separate from the subsequently developed 2014 Force Posture Agreement.

The missing list of bases to which US force have access

All these concerns, along with the new public relations notion of ‘collaborative facilities’, make the question of which ADF facilities the Force Posture Agreement give United States forces access to both strategically and politically pressing. Why so secret?

On 10 March 2023, an application under the Freedom of Information Act was filed with the Defence Department seeking ‘a copy of ‘Annex A’ to the Force Posture Agreement between the Government of Australia and the Government of the United States.’

On 28 April 2023, the responsible official responded to the application (Defence FOI 576/22/23), noting they had identified ‘one document as falling within the scope of the request’, but denied access to the document under section 33(a)(iii) of the FOI Act, because release of the document ‘would cause, or could reasonably be expected to cause, damage to the international relations of the Commonwealth. The release of this information could reasonably be expected to undermine Australia’s good working relations with another government. In particular, the disclosure of the document within scope could cause a loss of trust and confidence in the Australian Government, and as a result, foreign officials may be less willing to engage with Australian Government officials in the future.’

On 10 May 2023 the applicant requested a review of this decision as provided under the FOI Act. As of the time of writing, no result of the review has been forthcoming.

However, on 7 June 2023, separately from the ongoing FOIA application, the chair of the Independent and Peaceful Australia Network, Annette Brownlie, wrote to the Secretary of the Defence Department, Greg Moriarty, requesting access to Annex A of the Force Posture Agreement or to a list of Agreed Facilities and Areas under the Agreement.

On 27 June, Moriarty replied to Brownlie in surprising terms, given the progress of the FOIA application, its identification of a relevant document, refusal of access, and the pending review of that FOIA refusal:

‘Whilst the Force Posture Agreement refers to a potential ‘Annex A’ covering the Agreed Facilities and Areas, Annex A was not developed… Instead a Memorandum of Understanding on Agreed Facilities and Areas was later developed and signed by the U.S. Defence Secretary and Australia’s Minister for Defence, Kevin Andrews on 30 May 2015.’

Moriarty continued:

‘This Memorandum of Understanding is not publicly available due to its classification.’

On 13 July 2023 a FOIA application for access to Memorandum of Understanding on Agreed Facilities and Areas was submitted, and a reply is pending.

Why so silent?

There are a number of puzzling aspects to the Albanese government’s refusal to release the list of the Agreed Facilities and Areas to which US forces have access under the 2014 Force Posture Agreement or the MOU on Agreed Facilities and Areas a year later.

Not that this secrecy is Labor’s responsibility alone: prior to Moriarty’s belated disclosure last month, there appeared to be no Australian government reference to the MOU’s existence between May 2015 and June 2023. The only extant public record of the MOU’s existence appears to be a US Defence Department publicity photograph of former Minister of Defence Kevin Andrews signing the MOU on 30 May 2015.

It is also not entirely surprising that the Annex listing the bases concerned mentioned as a possibility in the Force Posture Agreement did not appear in the published text at the time. Whichever bases were contemplated or eventuated, basing agreements of almost any kind almost always require protracted negotiations, not least over non-strategic questions like responsibility for property development, financial terms, customs duties, and foreign personnel visa and taxation status.

More seriously, applying the Australian government’s doctrine of Full Knowledge and Concurrence (Article II (2)) to the provision of wide-ranging U.S. multiservice and contractor access to airbases and other bases from which war operations could potentially be launched would, if taken seriously, required some serious strategic and legal thought. As Iain Henry and Cam Hawker forewarned in the early stages of the development of the Force Posture Agreement, founding Australian control of the operations of US offensive – and, in the case of B-52 and B-2 bombers, possibly nuclear-armed – strategic platforms on the already shaky framework of ‘full knowledge and concurrence’ is much less plausible than even in the case of the intelligence facilities.

Either way, it is not entirely surprising that this process took the best part of a year, resulting, according to Moriarty, in the May 2015 MOU.

But the real question remains as to why Australian governments, and the Albanese government in particular, have been so determined to keep the list of bases secret.

A first consideration might be matters of defence security that could be imperilled by revelations that U.S. forces and contractors have access to a particular defence facility. In general terms, given the amount of publicly available information – not least from U.S. and Australian defence official media sources – about US access to at least several dozen ADF facilities, this is implausible. Moreover, discovering the presence of U.S. military and personnel in towns near defence facilities mostly located in rural and remote Australia would not test many journalists or foreign intelligence operatives with access to Google Earth or the local bars.

A second consideration might be, as was suggested by the reasons provided for refusing FOIA access to Annex A, that disclosure ‘could cause a loss of trust and confidence in the Australian Government’ and damage working relations with the United States. Again, in principle, such an outcome could be envisaged – if the United States was deeply concerned about such a revelation.

In fact, there is good reason to think this is not the case, and that indeed, the actual situation is probably the reverse – it is the Australian government, not that of the U.S., which is adamant the degree of access it is providing for U.S. forces and contractors should not be revealed to the Australian public.

The United States has made arrangements concerning access for US military forces to Agreed Facilities and Areas with a large number of countries around the world, under a range of Defence Cooperation Agreements, Status of Forces Agreements, Supplementary Defence Cooperation Agreements, and similarly titled agreements which use the explicit phrasing of ‘Agreed Facilities and Areas’.

A brief review of open source data shows that in recent years the U.S. has made agreements explicitly concerning access to ‘Agreed Facilities and Areas’ with a large number of allied and non-allied countries including, but likely not limited to, Afghanistan, Estonia, Ghana, Guatemala, Hungary, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Latvia, Lithuania, Netherlands (Curacao), Norway, Papua New Guinea, Poland, Senegal, Slovak Republic, and Spain.

While some of these agreements do not provide public data about which facilities are included as ‘Agreed Facilities and Areas’, some do, including at least five important US allies for which the hosting bases concerned are publicly named.

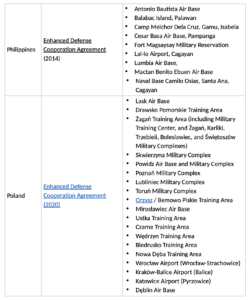

Table 1 identifies recent agreements with five US allies which publicly state which Agreed Facilities and Areas to which US forces are to have access under such agreements. Three such allies – Hungary, Norway, and Poland – are NATO allies; another, the Philippines, is returning to close allied status after an interregnum; and a fifth, the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, was a close ally of the United States until very recently. (In addition, Papua New Guinea has recently signed a Defence Cooperation Agreement with the United States. According to as-yet unconfirmed media sources with access to the reported text of the agreement, five PNG facilities, including two maritime ports and three airports, are included as Agreed Facilities and Areas.)

Table 1. Countries with defence agreements with United States publicly specifying Agreed Facilities and Areas to which US forces have access [Note: PNG release to media not officially confirmed]

The public identification in the text of these bilateral defence agreements as to which Agreed Facilities and Areas in these countries US forces are to have access would have required the consent of both governments concerned.

This implies that in at least these five cases of considerable diplomatic and strategic importance to the United States, both the US government and the hosting governments were agreeable to the disclosure of the listing of Agreed Facilities and Areas to which US forces have access.

To my knowledge, there has been no attempt by any of the allied governments involved, including the government of the United States, to reverse the decision to make publicly known these Agreed Facilities and Areas to which US forces have access in the countries concerned.

These examples of governments of both major United States allies and the United States accepting such publication of Agreed Facilities and Areas to which US forces have access make it reasonable to discount the claim by the government of Australia that disclosure of the list of Agreed Facilities and Areas under the MOU would necessarily be detrimental to relations of trust with another government.

More fundamentally still, the question then becomes ‘What have or did the governments of Hungary, Norway, the Philippines, and the former puppet government of Afghanistan, possess that Australian governments do not?’ The answer will have something to do with conceptions of genuine sovereignty and obligations to transparency foreign to Australian governments, particularly the incumbent Albanese government.

Author’s note: My thanks to Kellie Tranter, Annette Brownlie and Vince Scappatura.

![Table 1. Countries with defense agreements with United States publicly specifying

Agreed Facilities and Areas to which US forces have access

[Note: PNG release to media not officially confirmed]](https://johnmenadue.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Table-1-Countries-with-defence-agreements--286x300.png)