By Thomas A. Bass, August 4, 2017, MekongReview.

Everything wrong with the new ten-part PBS documentary on the Vietnam War is apparent in the first five minutes. A voice from nowhere intones about a war “begun in good faith” that somehow ran off the rails and killed millions of people. We see a firefight and a dead soldier in a body bag being winched into a helicopter, as the rotor goes thump, thump, thump, like a scene from Apocalypse Now. Then we cut to a funeral on Main Street and a coffin covered in Stars and Stripes, which multiply, as the camera zooms out, into dozens and then hundreds of flags, waving like a hex against warmongers who might be inclined to think that this film is insufficiently patriotic.

Everything right with the documentary is apparent in the next few minutes, as the film rolls back (literally running several scenes backward) into a trove of archival footage and music from the times and introduces the voices — many of them Vietnamese — that will narrate this history. The film relies heavily on writers and poets, including Americans Tim O’Brien and Karl Marlantes and the Vietnamese writers Le Minh Khue, and Bao Ninh, whose Sorrow of War ranks as one of the great novels about Vietnam or any war.

The even-handedness, the flag-draped history, bittersweet narrative, redemptive homecomings and the urge toward “healing” rather than truth are cinematic topoi that we have come to expect from Ken Burns and Lynn Novick through their films about the Civil War, Prohibition, baseball, jazz and other themes in United States history. Burns has been mining this territory for forty years, ever since he made his first film about the Brooklyn Bridge in 1981, and Novick has been at his side since 1990, when he hired her as an archivist to secure photo permissions for The Civil War and she proved the indispensable collaborator.

In their interviews, Burns does most of the talking, while the Yale-educated, former Smithsonian researcher hangs back. Novick receives joint billing in the credits to their films, but most people refer to them as Ken Burns productions. (After all, he is the one with an “effect” named after him: a film-editing technique, now standardised as a “Ken Burns” button, which enables one to pan over still photographs.) One wonders what tensions exist between Novick and Burns: the patient archivist and the sentimental dramatist.

The dichotomy between history and drama shapes all ten parts of the PBS series, which begins with the French colonisation of Vietnam in 1858 and ends with the fall of Saigon in 1975. As the film cuts from patient Novickian exposition to Burnsian close-ups, it sometimes feels as if it were edited by two people making two different movies. We can be watching archival footage from the 1940s of Ho Chi Minh welcoming the US intelligence officers who came to resupply him in his mountain redoubt, when suddenly the film shifts from black and white to colour and we are watching a former American soldier talk about his Viet Cong-induced fear of the dark, which makes him sleep with a night light, like his kids. Even before we get to Ho Chi Minh and his defeat of the French at Dien Bien Phu in 1954, we are watching a US marine describe his homecoming to a divided America in 1972, a homecoming that he says was harder than fighting the Viet Cong.

By Episode Two, “Riding the Tiger” (1961-1963), we are heading deep into Burns territory. The war has been framed as a civil war, with the United States defending a freely elected democratic government in the south against Communists invading from the north. American boys are fighting a godless enemy that Burns shows as a red tide creeping across maps of Southeast Asia and the rest of the world.

The historical footage in Episode One, “Déjà Vu” (1858-1961), which disputes this view of the war, is either ignored or misunderstood. Southern Vietnam was never an independent country. From 1862 to 1949, it was the French colony of Cochinchina, one of the five territorial divisions in French Indochina (the others being Tonkin, Annam, Cambodia and Laos). Defeated French forces regrouped in southern Vietnam after 1954, which is when US Air Force colonel and CIA agent Edward Lansdale began working to elevate this former colony to nationhood. The US installed Ngo Dinh Diem as south Vietnam’s autocratic ruler, aided him in wiping out his enemies and engineered an election that Diem stole, with 98.2 per cent of the popular vote.

The key moment in Lansdale’s creation was the month-long Battle of the Sects, which began in April 1955. (The battle is not mentioned in the film. Nor is Lansdale identified in a photo of him seated next to Diem.) A cable had been drafted instructing the US ambassador to get rid of Diem. (A similar cable, sent a decade later, would greenlight Diem’s assassination.) The evening before the cable went out, Diem launched a fierce attack on the Binh Xuyen crime syndicate, led by river pirate Bay Vien, who had 2,500 troops under his command. When the battle was over, a square mile of Saigon had been levelled and 20,000 people left homeless.

The French financed their colonial empire in Asia through the opium trade (another fact left out of the film). They skimmed the profits from Bay Vien’s river pirates, who were also licensed to run the national police and Saigon’s brothels and gambling dens. Diem’s attack on the Binh Xuyen was essentially an attack on the French. It was an announcement by the CIA that the French were finished in Southeast Asia. The US had financed their colonial war, paying up to 80 per cent of the cost, but after the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu, it was time for the losers to get out of town.

Once the river pirates were defeated and other opposition groups such as the Hoa Hao and the Cao Dai neutralised with CIA bribes, Diem and Lansdale began making a “free” Vietnam. By 23 October 1955, Diem was claiming his electoral victory. Three days later he announced the creation of the Republic of Vietnam, better known as South Vietnam. He cancelled the elections intended to unify northern and southern Vietnam — elections that President Eisenhower and everyone else knew would have been won by Ho Chi Minh — and began building the autocratic police state that survived for twenty years, before collapsing into the dust of the last helicopter lifting off from the US Embassy.

Lansdale was a former advertising man. He had worked on the Levi Strauss account when it started selling blue jeans nationally. He knew how to sell blue jeans. He knew how to sell a war. Anyone knowledgeable about the history of Vietnam and its prolonged struggle against French colonialism could see what was happening. “The problem was trying to cover something every day as news when in fact the real key was that it was all derivative of the French Indo-China war, which is history,” said former New York Times reporter David Halberstam. “So you really should have had a third paragraph in each story which should have said, ‘All of this is shit and none of this means anything because we are in the same footsteps as the French and we are prisoners of their experience.’”

Even the language of the Second Indochina War was borrowed from the French, who spoke of “light at the end of the tunnel” and the jaunissement (yellowing) of their army, which the US later called Vietnamisation. France dropped gelatinised petroleum, napalm, on Vietnam in la sale guerre, the “dirty war”, which the US made even dirtier with Agent Orange and other chemical weapons.

If these facts were known to government officials and journalists, they were known to everyone after Daniel Ellsberg released the Pentagon Papers in 1971. Forty volumes of top secret documents exposed the lies of every US administration from Truman and Eisenhower on to Kennedy and Johnson. The Pentagon Papers describe how the American public was deceived into supporting France’s effort to recolonise Vietnam. They recount Lansdale’s covert operations and US culpability for scuttling the elections meant to reunify Vietnam. They describe a war for independence that the US never stood a chance of winning, even with half a million troops on the ground. The enterprise was actually directed at containing China and playing a global game of chicken against Russia. “We must note that South Vietnam (unlike any of the other countries in Southeast Asia) was essentially the creation of the United States”, wrote Leslie Gelb, who directed the project, in his Pentagon Papers summary. “Vietnam was a piece on a chessboard, not a country,” Gelb tells Burns and Novick.

More than eighty people were interviewed by the film-makers over the ten years they gathered material for The Vietnam War, but one glaring exception is Daniel Ellsberg. Ellsberg, a former Marine Corps platoon leader, was a gung-ho warrior when he worked for Lansdale in Vietnam from 1965 to 1967. But as the war dragged on, and Ellsberg feared that Nixon would try to end the stalemate with nuclear weapons (the French had already asked Eisenhower to drop the bomb on Vietnam), he flipped to the other side.

Ellsberg today is a fierce critic of US nuclear policy and military adventures from Vietnam to Iraq. His absence from the film, except in archival footage, confirms its conservative credentials. Funded by Bank of America, David Koch and other corporate sponsors, the documentary relies extensively on former generals, CIA agents and government officials, who are not identified by rank or title, but merely by their names and anodyne descriptions such as “adviser” or “special forces”. A partial list includes:

• Lewis Sorley, a third-generation West Point graduate who believes the US won the war in 1971 and then threw away its victory by “betraying” its allies in the south (even though they had been supplied with $6 billion of US weapons before they collapsed to the advancing North Vietnamese in 1975).

• Rufus Phillips, one of Lansdale’s “black artists” who worked for many years in psychological operations and counterinsurgency.

• Donald Gregg, organiser of the Iran-contra arms-for-hostages scandal and CIA adviser to the Phoenix program and other assassination teams.

• John Negroponte, former director of national intelligence and ambassador to international hotspots targeted for covert operations.

• Sam Wilson, the US Army general and Lansdale protégé who coined the term “counterinsurgency”.

• Stuart Herrington, a US Army counterintelligence officer known for his “extensive interrogation experience”, stretching from Vietnam to Abu Ghraib.

• Robert Rheault, who was the model for Colonel Kurtz, the renegade warrior in Apocalypse Now. Rheault was the colonel in charge of special forces in Vietnam, before he was forced to resign when he and five of his men were charged with premeditated murder and conspiracy. The Green Berets had killed one of their Vietnamese agents, suspected of being a turncoat, and dumped his body in the ocean.

The day that Nixon got the army to drop criminal charges against Rheault is the day that Daniel Ellsberg decided to release the Pentagon Papers. “I thought: I’m not going to be part of this lying machine, this cover-up, this murder, anymore” wrote Ellsberg in Secrets: A Memoir of Vietnam and the Pentagon Papers. “It’s a system that lies automatically, at every level, from bottom to top — from sergeant to commander in chief — to conceal murder.” The Green Beret case, said Ellsberg, was a version “of what that system had been doing in Vietnam, on an infinitely larger scale, continuously for a third of a century”.

Burns and Novick rely extensively on another person — in fact, she accompanied them on their promotional tour for the film — who is identified in the documentary as “Duong Van Mai, Hanoi” and then later as “Duong Van Mai, Saigon”. This is the maiden name of Duong Van Mai Elliott, who has been married for fifty-three years to David Elliott, a former RAND interrogator in Vietnam and professor of political science at Pomona College in California. Since going to school at Georgetown University in the early 1960s, Mai Elliott has lived far longer in the United States than in Vietnam.

Elliott, herself a former RAND employee, is the daughter of a former high government official in the French colonial administration. After the French defeat in the First Indochina War, her family moved from Hanoi to Saigon, except for Elliott’s sister, who joined the Viet Minh in the north. This allows Elliott to insist — as she does repeatedly in her public appearances — that Vietnam’s was a “civil war”. The war divided families like hers, but anti-colonialist fighters arrayed against colonialist sympathisers do not constitute a civil war. No one refers to the First Indochina War as a civil war. It was an anti-colonial struggle that shaded into a repeat performance, except that by this time Lansdale and Diem had created the facsimile of a nation state. Americans loath to help France re-establish its colonial empire in Asia could feel good about defending the white hats in a civil war. Elliott, an eloquent and earnest victim of this war, embodies the distressed damsel whom US soldiers were trying to save from Communist aggression.

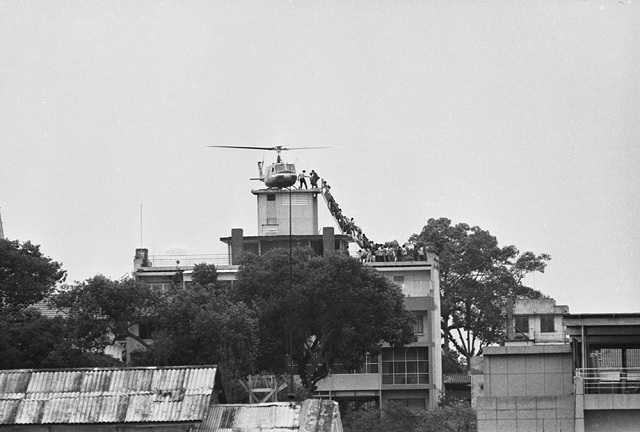

Once Lansdale is erased from the history of the Vietnam War, we settle into watching eighteen hours of carnage, interspersed with talking-head testimonials that reappear, first as sound bites, then as longer snippets and finally as full-blown interviews. These are surrounded by historical footage that rolls from the First Indochina War into the Second and then focuses on battles at Ap Bac and Khe Sanh, the Tet Offensive, bombing campaigns over North Vietnam, the release of US POWs and the last helicopter lifting off from the roof of the US Embassy (which was actually the roof of a CIA safe house at 22 Ly Tu Trong Street). By the end of the film — which is absorbing and contentious, like the war itself — more than 58,000 US troops, a quarter of a million South Vietnamese troops, a million Viet Cong and North Vietnamese troops and 2 million civilians (mainly in the south), not to mention tens of thousands more in Laos and Cambodia, will have died.

The Vietnam footage is set in the context of events back in the US during the six presidencies that sustained this chaos (beginning with Harry Truman at the end of World War II). The camera rolls through the assassinations of John Kennedy and Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, the police riots at the Chicago Democratic convention in 1968 and various anti-war protests, including the one in which four students were shot dead at Kent State University. The film includes taped conversations of Nixon and Kissinger hatching their schemes. (“Blow the safe and get it”, Nixon says of incriminating evidence at the Brookings Institute). It shows Walter Cronkite losing faith in the Vietnam venture and the Watergate burglary and Nixon’s resignation and the struggle over building Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial (the “gash of shame” that has turned into a poignant lieu de mémoire).

For many, the film will remind us of what we already know. For others, it will be an introduction to twenty years of American arrogance and overreach. People might be surprised to learn of Nixon’s treason in sabotaging Lyndon Johnson’s peace negotiations in 1968, in order to boost his own election chances. This is not the only time in this documentary that back-channel international treachery resonates with current events. Viewers might also be surprised to learn that the battle of Ap Bac in 1963, a major defeat for the Army of the Republic of Vietnam and its US advisers, was declared a victory, because the enemy, after killing eighty ARVN soldiers and three US advisers, melted back into the countryside. Only in the thick-headed logic of the US military could securing a bombed-out rice paddy be called a victory, but time and again, year after year, the United States would “win” every battle it fought for useless mountain tops and rice paddies that were seized while the enemy carried off their dead, regrouped and attacked again somewhere else.

With journalists reporting defeat and the Pentagon trumpeting victory, the “credibility gap”, which by now had grown into a chasm, began to appear, along with attacks on the press for being disloyal and for somehow “losing” the war. Complaints about “fake news” and journalists as “enemies of the people” are more social sequelae that can be traced back to the Vietnam War. When Morley Safer documented marines torching thatch-roofed houses in the village of Cam Ne in 1965, Safer’s name was blackened by accusations that he had supplied the Marines with their Zippo lighters. Disinformation, psychological war, covert operations, news leaks, spin and official lies are yet more living legacies from Vietnam.

The film’s best narrative gambit is its reliance on writers and poets, the two key figures being Bao Ninh (whose real name is Hoang Au Phuong), the former infantryman who returned home after six years of fighting his way down the Ho Chi Minh Trail to write The Sorrow of War, and former marine Tim O’Brien, who came back from his war to write The Things They Carried and Going After Cacciato. The film ends with O’Brien reading about soldiers carrying memories from Vietnam, and then the credits roll, giving us Mai Elliott’s full name and other people’s identities.

This is when I began playing the footage again, rolling through Episode One, surprised not by how much had been remembered, but by how much had been left out or forgotten. Many good documentaries have been made about the Vietnam War, by Canadians, French and other Europeans. American journalists Stanley Karnow and Drew Pearson have grappled with presenting the war in TV documentaries. But the tenacity with which the US has forgotten the lessons of Vietnam, burying them under misplaced patriotism and wilful disregard for history, bump it out of contention for making a great movie about this war.

Why, for example, are the film’s interviews shot exclusively as close-ups? If the camera had pulled back, we would have seen that former Senator Max Cleland has no legs — he lost them to “friendly fire” at Khe Sanh. And what if Bao Ninh and Tim O’Brien had been allowed to meet each other? Their reminiscing would have brought the meaningless mayhem of the war into the present. And instead of its search for “closure” and healing reconciliation, what if the film had reminded us that US special forces are currently operating in 137 of the planet’s 194 countries, or 70 per cent of the world?

Like most Burns and Novick productions, this one comes with a companion volume, The Vietnam War: An Intimate History, which is being released at the same time as the PBS series. Written by Burns and his longtime amanuensis, Geoffrey C Ward, the book — an oversized volume weighing nearly two kilograms — wears the same bifocals as the film. It shifts from historical exegesis to autobiographical reflection, and features many of the photographs that made Vietnam the apex of war photography. The famous shots include Malcolm Brown’s burning monk; Larry Burrows’s photo of a wounded marine reaching out to his dying captain; Nick Ut’s photo of Kim Phuc running naked down the road with napalm burning her flesh; Eddie Adams’s photo of general Nguyen Ngoc Loan shooting a VC sapper in the head; and Hugh Van Es’s photo of refuges climbing a rickety ladder into the last CIA helicopter flying out of Saigon.

Burns’s binocular vision in some ways works better in the book than the movie. The book has room to go into detail. It provides more history while at the same time presenting poignant reflections by Bao Ninh, female war correspondent Jurate Kazickas, and others. Edward Lansdale and the Battle of the Sects appear in the book, but not the film, along with details about the 1955 State Department cable that directed that Ngo Dinh Diem be overthrown — before the US reversed course and bought into the creation of Diem’s South Vietnam. Also here in chilling detail are Nixon and Kissinger’s conversations about prolonging the war in order to win elections and save face.

The book has the added benefit of including five essays commissioned by leading scholars and writers. Among these is a piece by Fredrik Logevall speculating on what might have happened if Kennedy had not been assassinated; a piece by Todd Gitlin on the anti-war movement; and a reflection by Viet Thanh Nguyen on life as a refugee, which, in his case, went from working in his parents’ grocery store in San Jose to winning the 2016 Pulitzer Prize.

In 1967, eight years before the war’s end, Lyndon Johnson is announcing “dramatic progress”, with “the grip of the VC on the people being broken”. We see mounds of dead Viet Cong heaved into mass graves. General Westmoreland assures the president that the war is reaching “the crossover point”, when more enemy soldiers are being killed than recruited. Jimi Hendrix is singing “Are You Experienced” and a vet is describing how “racism really won” in “intimate fighting” that taught him how to “waste gooks” and “kill dinks”.

By 1969, Operation Speedy Express in the Mekong Delta is reporting kill ratios of 45:1, with 10,889 Viet Cong fighters killed but only 748 weapons recovered. Kevin Buckley and Alexander Shimkin of Newsweek estimate that half the people killed are civilians. By the time the kill ratios have climbed to 134:1, the US military is massacring civilians at My Lai and elsewhere. Edward Lansdale, by then a general, said about this final stage of the war he had set in motion (quoting from Robert Taber’s War of the Flea): “There is only one means of defeating an insurgent people who will not surrender, and that is extermination. There is only one way to control a territory that harbours resistance, and that is to turn it into a desert. Where these means cannot, for whatever reason, be used, the war is lost.”

![]()

The Vietnam War

A film by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick

PBS: 2017

The Vietnam War: An Intimate History

Geoffrey C Ward and Ken Burns

Knopf: 2017

One Response

The Vietnam crime, just like Korea was nothing but interference in other countries civil wars. It was the U.S.A. thinking it was and still is the World’s policeman, albeit a policeman without any idea of true law enforcement, one that enforces his prejudices and political ideas on others.