By Peace Science Digest, June 8, 2022

This analysis summarizes and reflects on the following research: Otto, D. (2020). Rethinking ‘peace’ in international law and politics from a queer feminist perspective. Feminist Review, 126(1), 19-38. DOI:10.1177/0141778920948081

Talking Points

- The meaning of peace is often framed by war and militarism, highlighted by stories that define peace as evolutionary progress or stories that focus on militarized peace.

- The UN Charter and international laws of war ground their conception of peace in a militarist framework, rather than working towards war elimination.

- Feminist and queer perspectives on peace challenge binary ways of thinking about peace, thereby contributing to a reimagination of what peace means.

- Stories from grassroots, non-aligned peace movements from around the world help to imagine peace outside the frames of war through a rejection of a militarized status quo.

Key Insight for Informing Practice

- As long as peace is framed by war and militarism, peace and anti-war activists will always be in a defensive, reactive position in debates on how to respond to mass violence.

Summary

What does peace mean in a world with endless war and militarism? Dianne Otto reflects on the “specific social and historical circumstances that profoundly influence how we think about [peace and war].” She pulls from feminist and queer perspectives to imagine what peace could mean independent of a war system and militarization. In particular, she is concerned with how international law has worked to sustain a militarized status quo and whether there is an opportunity to re-think the meaning of peace. She focuses on strategies to resist deeper militarization through everyday practices of peace, drawing on examples of grassroots peace movements.

Feminist peace perspective: “’[P]eace’ as not only the absence of ‘war’ but also as the realization of social justice and equality for everyone… [F]eminist prescriptions [for peace] have remained relatively unchanged: universal disarmament, demilitarization, redistributive economics and—imperative to achieving all these goals—the dismantling of all forms of domination, not least of all hierarchies of race, sexuality and gender.”

Queer peace perspective: “[T]he need to question orthodoxies of all kinds…and to resist the binary ways of thinking that have so distorted our relationships with each other and the non-human world, and celebrate instead the many different ways of being human in the world. Queer thinking opens the possibility of ‘disruptive’ gender identities able to challenge the male/female dualism that sustains militarism and hierarchies of gender by associating peace with femininity…and conflict with manliness and ‘strength’.”

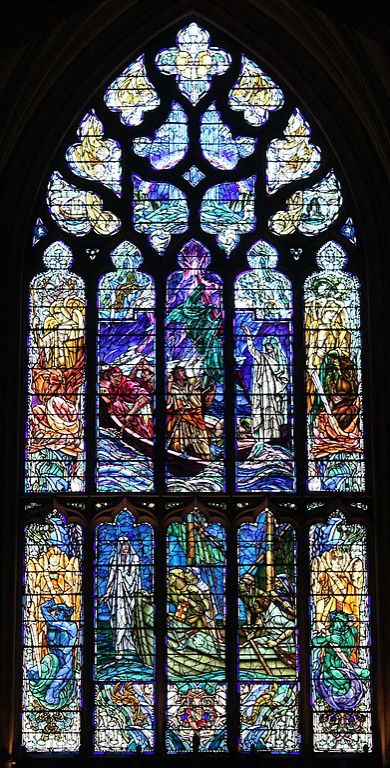

To frame the discussion, Otto tells three stories that situate differing conceptions of peace with respect to specific social and historical circumstances. The first story focuses on a series of stained-glass windows located at the Peace Palace in The Hague (view below). This art piece depicts peace through an “evolutionary progress narrative of the Enlightenment” via stages of human civilization and centers white men as the actors in all stages of development. Otto questions the implications of treating peace as an evolutionary process, arguing that this narrative justifies wars if they are waged against the “uncivilized” or are believed to have “civilizing effects.”

The second story focuses on demilitarized zones, namely the DMZ between North and South Korea. Represented as an “enforced or militarised peace…rather than evolutionary peace,” the Korean DMZ (ironically) serves as a wildlife refuge even as it is continuously patrolled by two militaries. Otto asks if a militarized peace truly embodies peace when demilitarized zones are made safe for nature but “dangerous for human beings?”

The final story centers on the San Jośe de Apartadó peace community in Colombia, a grassroots demilitarized community that declared neutrality and refused to participate in the armed conflict. Despite attacks from paramilitary and national armed forces, the community remains intact and supported by some national and international legal recognition. This story represents a new imagination of peace, bound by a feminist and queer “rejection of the gendered dualism of war and peace [and a] commitment to complete disarmament.” The story also challenges the meaning of peace displayed in the first two stories by “striving to create conditions for peace in the midst of war.” Otto wonders when international or national peace processes will work “to support grassroots peace communities.”

Turning to the question of how peace is conceived in international law, the author focuses on the United Nations (UN) and its founding purpose to prevent war and build peace. She finds evidence for the evolutionary narrative of peace and for militarized peace in the UN Charter. When peace is coupled with security, it signals a militarized peace. This is evident in the Security Council’s mandate to use military force, embedded in a masculinist/realist viewpoint. The international law of war, as it is influenced by the UN Charter, “helps to disguise the violence of the law itself.” In general, international law since 1945 has become more concerned with “humanizing” war rather than working towards its elimination. For example, exceptions to the prohibition of the use of force have been weakened over time, once being acceptable in cases of self-defense to now being acceptable “in anticipation of an armed attack.”

References to peace in the UN Charter that are not coupled with security could provide a means to reimagine peace but rely on an evolutionary narrative. Peace is associated with economic and social progress that, in effect, “operates more as a project of governance than one of emancipation.” This narrative suggests that peace is made “in the image of the West,” which is “deeply embedded in the peace work of all multilateral institutions and donors.” Narratives of progress have failed to build peace because they rely on reimposing “imperial relations of domination.”

Otto ends by asking, “what do imaginaries of peace start to look like if we refuse to conceive of peace through the frames of war?” Drawing on other examples like the Colombian peace community, she finds inspiration in grassroots, non-aligned peace movements that directly challenge the militarized status quo—such as the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp and its nineteen-year campaign against nuclear weapons or the Jinwar Free Women’s Village that provided safety for women and children in Northern Syria. Despite their purposefully peaceful missions, these grassroots communities operate(d) under extreme personal risk, with states portraying these movements as “threatening, criminal, treasonous, terrorist—or hysterical, ‘queer’, and aggressive.” However, peace advocates have much to learn from these grassroots peace movements, especially in their deliberate practice of everyday peace to resist a militarized norm

Informing Practice

Peace and anti-war activists are often cornered into defensive positions in debates on peace and security. For instance, Nan Levinson wrote in The Nation that anti-war activists are facing a moral dilemma in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, detailing that “positions have ranged from blaming the United States and NATO for provoking Russia’s invasion to charging Washington with not negotiating in good faith, to worrying about provoking Russian President President Putin further [to] calling out defense industries and their supporters [to] hailing the Ukrainians for their resistance and affirming that people indeed do have the right to defend themselves.” The response can appear scattered, incoherent, and, considering reported war crimes in Ukraine, insensitive or naïve to an American public audience already primed to support military action. This dilemma for peace and anti-war activists demonstrates Dianne Otto’s argument that peace is framed by war and a militarized status quo. As long as peace is framed by war and militarism, activists will always be in a defensive, reactive position in debates on how to respond to political violence.

One reason why advocating for peace to an American audience is so challenging is the lack of knowledge or awareness about peace or peacebuilding. A recent report by Frameworks on Reframing Peace and Peacebuilding identifies common mindsets among Americans about what peacebuilding means and offers recommendations on how to more effectively communicate peacebuilding. These recommendations are contextualized in recognition of a highly militarized status quo among the American public. Common mindsets on peacebuilding include thinking about peace “as the absence of conflict or a state of inner calm,” assuming “that military action is central to security,” believing that violent conflict is inevitable, believing in American exceptionalism, and knowing little about what peacebuilding involves.

This lack of knowledge creates opportunities for peace activists and advocates to put in the long-term, systemic work to reframe and publicize peacebuilding to a broader audience. Frameworks recommends that emphasizing the value of connection and interdependence is the most effective narrative to build support for peacebuilding. This helps to make a militarized public understand that they have a personal stake in a peaceful outcome. Other narrative frames recommended include “emphasiz[ing] the active and ongoing character of peacebuilding,” using a metaphor of building bridges to explain how peacebuilding works, citing examples, and framing peacebuilding as cost-effective.

Building support for a fundamental reimagining of peace would allow peace and anti-war activists to set the terms of debate on questions about peace and security, rather than having to revert to defensive and reactive positions to a militarized response to political violence. Making connections between long-term, systemic work and the day-to-day demands of living in a highly militarized society is an incredibly difficult challenge. Dianne Otto would advise to focus on everyday practices of peace to reject or resist militarization. In truth, both approaches—a long-term, systemic reimagining and daily acts of peaceful resistance—are critically important to deconstructing militarism and rebuilding a more peaceful and just society. [KC]

Questions Raised

- How can peace activists and advocates communicate a transformative vision for peace that rejects a militarized (and highly normalized) status quo when military action garners public support?

Continued Reading, Listening, and Watching

Pineau, M. G., & Volmet, A. (2022, April 1). Building the bridge to peace: Reframing peace and peacebuilding. Frameworks. Retrieved June 1, 2022, from https://www.frameworksinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/FWI-31-peacebuilding-project-brief-v2b.pdf

Hozić, A., & Restrepo Sanín, J. (2022, May 10). Reimagining the aftermath of war, now. LSE blog. Retrieved June 1, 2022, from https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/wps/2022/05/10/reimagining-the-aftermath-of-war-now/

Levinson, N. (2022, May 19). Anti-war activists are facing a moral dilemma. The Nation. Retrieved June 1, 2022, from https://www.thenation.com/article/world/ukraine-russia-peace-activism/

Müller, Ede. (2010, July 17). The global campus and the Peace Community San José de Apartadó, Colombia. Associação para um Mundo Humanitário. Retrieved June 1, 2022, from

https://vimeo.com/13418712BBC Radio 4. (2021, September 4). The Greenham effect. Retrieved June 1, 2022, from https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m000zcl0

Women Defend Rojava. (2019, December 25). Jinwar – A women’s village project. Retrieved June 1, 2022, from

Organizations

CodePink: https://www.codepink.org

Women Cross DMZ: https://www.womencrossdmz.org

Keywords: demilitarizing security, militarism, peace, peacebuilding

Photo credit: Banksy