By Dave Lindorff, World BEYOND War, July 12, 2020

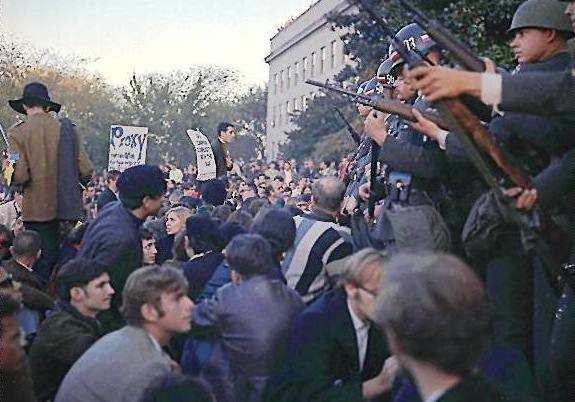

Dave Lindorff at lower right, facing away from the camera, at the Pentagon on Oct. 21, 1967.

I have been an activist and an activist journalist since 1967, when I turned 18 as a high school senior and, having concluded that the Vietnam War was criminal, decided not to carry a draft card, to skip applying the next fall at college registration for a student deferment from induction, and to refuse to see if and when my call-up came. My decision become confirmed that October when I was arrested on the Mall of the Pentagon during the Mobe Demonstration, dragged through a line or armed federal troops, beaten by U.S. marshals and tossed into a wagon for delivery to the federal prison at Occoquan, VA to await arraignment on trespass and resisting arrest charges.

But that begs the question: Why did I become an anti-war, anti-Establishment activist when so many others of my generation either accepted being drafted and went to fight in that war, or more often, figured out clever ways to avoid the fighting or to avoid the draft (claiming bone spurs like Trump, or signing up for the National Guard and checking “no foreign postings” like GW Bush, claiming Conscientious Objector status, losing a lot of weight, faking being a “fag,” fleeing to Canada, or whatever worked).

I guess I’d have to start with my mother, a sweet “homemaker” who did two years of college learning secretarial skills in Chapel Hill and served proudly as a Navy WAVE during WWII (mostly doing office jobs in uniform in the Brooklyn, NY Navy Yard).

My mom was a born naturalist. Born (literally) and born in a huge log cabin (formerly a dance hall) outside of Greensboro, NC, she was a classic “Tom boy,” always off catching animals, raising orphaned critters, etc. She loved all living things and taught that to me and my younger brother and sister.

She taught us how to catch frogs, snakes, and butterflies, caterpillars, etc., how to learn about them by keeping them briefly, and then about the virtue of letting them go, too.

Mom had a phenomenal skill when it came to raising little animals, whether it was some baby bird fallen from a nest, still featherless and fetal-looking, or tiny baby raccoons that were delivered to her by someone who had hit the mother with a car and found them huddled by the side of the road (we raised them as pets, letting the tamest live in the house with our cats and Irish Setter).

I had a brief 12-year-old infatuation with a single-shot Remington .22 rifle that I somehow prevailed on my engineering professor dad and my reluctant mom to let me buy with my own money. With that gun, and the hollow-point and other bullets I was able to buy on my own from the local hardware store, I and my gun-owning buddies of similar age used to wreak havoc in the woods, mostly shooting at trees, trying to cut them down with a row of hits across smaller trunks with the hollow points, but occasionally aiming at birds. I confess to having hit a few at great distance, never finding them after seeing them fall. It was more a matter of showing my skill at aiming than of killing them, which seemed a bit abstract. That is until I once went hunting for grouse a week before Thanksgiving with my good friend Bob whose family owned several shotguns. Our goal on that outing was to shoot our own birds and cook them for the holiday for our own consumption. We spent hours not seeing any grouse, but I finally flushed one. I fired wildly as it took off and the few pellets of shot that hit it knocked it down but it ran off into the bush. I ran after it, nearly getting my head blown off by my pal, who in the excitement fired off a round of his own at the fleeing bird as I was running after it. Luckily for me he missed both me and the bird.

I found my wounded grouse finally in the brush and caught it, picking up the struggling animal. My hands quickly became bloody from the bleeding wounds caused by my shot. I had my hands around the animal’s wings so it couldn’t struggle but it was frantically looking around. I began to cry, horrified at the suffering I had caused. Bob came up, also upset. I was pleading, “What do we do? What do we do? It’s suffering!” Neither of us had the guts to wring its little neck, which any farmer would have known how to do right away.

Instead, Bob told me to hold the grouse out and placed the end of the barrel of his reloaded shotgun behind the bird’s head and pulled the trigger. After a loud “blam!” I found myself holding the still body of a bird body with no neck or head.

I brought my kill home, my mom got the feathers off and roasted it for me for Thanksgiving, but I couldn’t really eat it. Not just because it was full of lead shot, but because of feelings of massive guilt. I never again shot or deliberately killed another living thing.

For me that grouse hunt was a turning point; a validation of the view I’d been raised on by my Mom that living things are sacred.

I guess the next big influence on me was folk music. I was very involved as a guitarist and player American folk music. Living in the university town of Storrs, CT, (UConn), where the general political perspective was support for civil rights, and opposition to war, and where the influence of the Weavers, Pete Seeger, Trini Lopez, Joan Baez, Bob Dylan , etc., was profound, and being for peace just came naturally in that milieu. Not that I was political in my early teens. Girls, running X-Country and t rack, jamming at the weekly coffeehouse in the community room of the Congregational Church near campus, and playing guitar with friends filled my days outside of school.

Then, as I was 17 and a senior facing draft registration in April, I signed up for a team-taught humanities program that featured comparative religion and philosophy, history, and art. Everyone in the class had to do a multimedia presentation touching on all those fields, and I picked the Vietnam War as my topic. I ended up researching the US war there, learned, through readings in the Realist, Liberation News Service, Ramparts and other such publications I learned about US atrocities, the use of napalm on civilians and other horrors that turned me permanently against the war, into a draft resister, and set me on the path of a lifetime of radical activism and journalism.

I think, looking back, that the course of my thinking was prepared by my mother’s love of animals, salted by the experience of killing an animal up close and personal with a gun, the milieu of the folk movement, and finally confronting both the reality of the draft and the truth of the horrors of the Vietnam War. I want to think almost anyone having those experiences would have ended up where I ended up.

DAVE LINDORFF has been a journalist for 48 years. Author of four books, he is also founder of the collectively run alternative journalist news site ThisCantBeHappening.net

He is a 2019 winner of an “Izzy” Award for Outstanding Independent Journalism from the Ithaca, NY-based Park Center for Independent Media.