by David Swanson, Let’s Try Democracy, May 31, 2021

I wish I were joking, even a little. Malcolm Gladwell’s book, The Bomber Mafia, maintains that Haywood Hansell was essentially Jesus tempted by the Devil when he refused to burn Japanese cities to the ground. Hansell was replaced, and Curtis LeMay put in charge of U.S. bombings of Japan during WWII. LeMay, Gladwell tells us, was none other than Satan. But what was very much needed, Gladwell claims, was Satanic immorality — the willingness to intentionally incinerate perhaps a million or so men, women, and children to advance one’s career. Only that and nothing else could have won the war most quickly, which created prosperity and peace for one and all (except the dead, I suppose, and anyone involved in all the subsequent wars or subsequent poverty). But in the end, WWII was only a battle, and the larger war was won by Hansell-Jesus because his dream of humanitarian precision bombing has now been realized (if you’re OK with murder by missile and willing to overlook that precision bombings have been used for years to kill mostly unknown innocent people while generating more enemies than they eliminate).

Gladwell begins his filthy piece of war normalization by admitting that his first short story, written as a child, was a fantasy about Hitler surviving and coming back to get you — in other words, the basic narrative of U.S. war propaganda for 75 years. Then Gladwell tells us that what he loves is obsessive people — no matter whether they’re obsessed with something good or something evil. Subtly and otherwise Gladwell builds a case for amorality, not just immorality, in this book. He starts by claiming that the invention of the bomb sight solved one of the 10 biggest technological problems of half a century. That problem was how to drop a bomb more accurately. Morally, that’s an outrage, not a problem to be lumped, as Gladwell lumps it, with how to cure diseases or produce food. Also, the bomb sight was a major failure that did not solve this supposedly critical problem, and Gladwell recounts that failure along with dozens of others in a stream of rolling SNAFUs that he treats as some sort of character-building signs of audacity, boldness, and christiness.

The goal of the “Bomber Mafia” (Mafia, like Satan, being a term of praise in this book) was supposedly to avoid the terrible ground war of WWI by planning for air wars instead. This, of course, worked out wonderfully, with WWII killing many more people than WWI by combining ground and air wars — although there’s not a single word in the book about ground fighting in WWII or the existence of the Soviet Union, because this is a U.S. book about the greatest generation waging the greatest war for America the Great; and the greatest break came at the greatest university (Harvard) with the successful test of the greatest tool of Satan our Savior, namely Napalm.

But I’m getting ahead of the story. Before Jesus makes an appearance, Martin Luther King Jr. has to do so, of course. You see, the dream of humanitarian air war was almost exactly like Dr. King’s dream of overcoming racism — apart from every possible detail. Gladwell doesn’t accept that this comparison is ludicrous, but calls the Dream of Air Wars “audacious” and turns immediately from the idea that bombing will bring peace to discussion of an amoral technological adventure. When Gladwell quotes a commentator suggesting that the inventor of the bomb sight would have attributed its invention to God, for all we can tell Gladwell probably agrees. Soon he’s in raptures over how the invention of the bomb sight was going to make war “almost bloodless,” and over the humanitarianism of the U.S. military bombing theorists who make up the Bombing Mafia devising schemes to bomb water supplies and power supplies (because killing large populations more slowly is divine).

Half the book is random nonsense, but some of it is worth repeating. For example, Gladwell believes that the Air Force Chapel in Colorado is especially holy, not just because it looks like they worship air wars, but also because it leaks when it rains — a major accomplishment once failure has become success, it seems.

The background of how WWII was created, and therefore how it might have been avoided, is given a total of five words in Gladwell’s book. Here are those five words: “But then Hitler attacked Poland.” Gladwell jumps from that to praising investment in preparing for unknown wars. Then he’s off on a debate between carpet bombing and precision bombing in Europe, during which he notes that carpet bombing doesn’t move populations to overthrow governments (pretending this is because it doesn’t greatly disturb people, as well as admitting that it generates hatred of those doing the bombing, and skirting the fact that governments tend not to actually care about the suffering within their borders, as well as skirting any application of the counter-productiveness of bombing to current U.S. wars, and — of course — putting up a pretense that Britain never bombed civilians until long after Germany did). There’s also not one word about the Nazis’ own bombing mafia later working for the U.S. military to help destroy places like Vietnam with Satan’s own Dupont Better Living Through Chemistry.

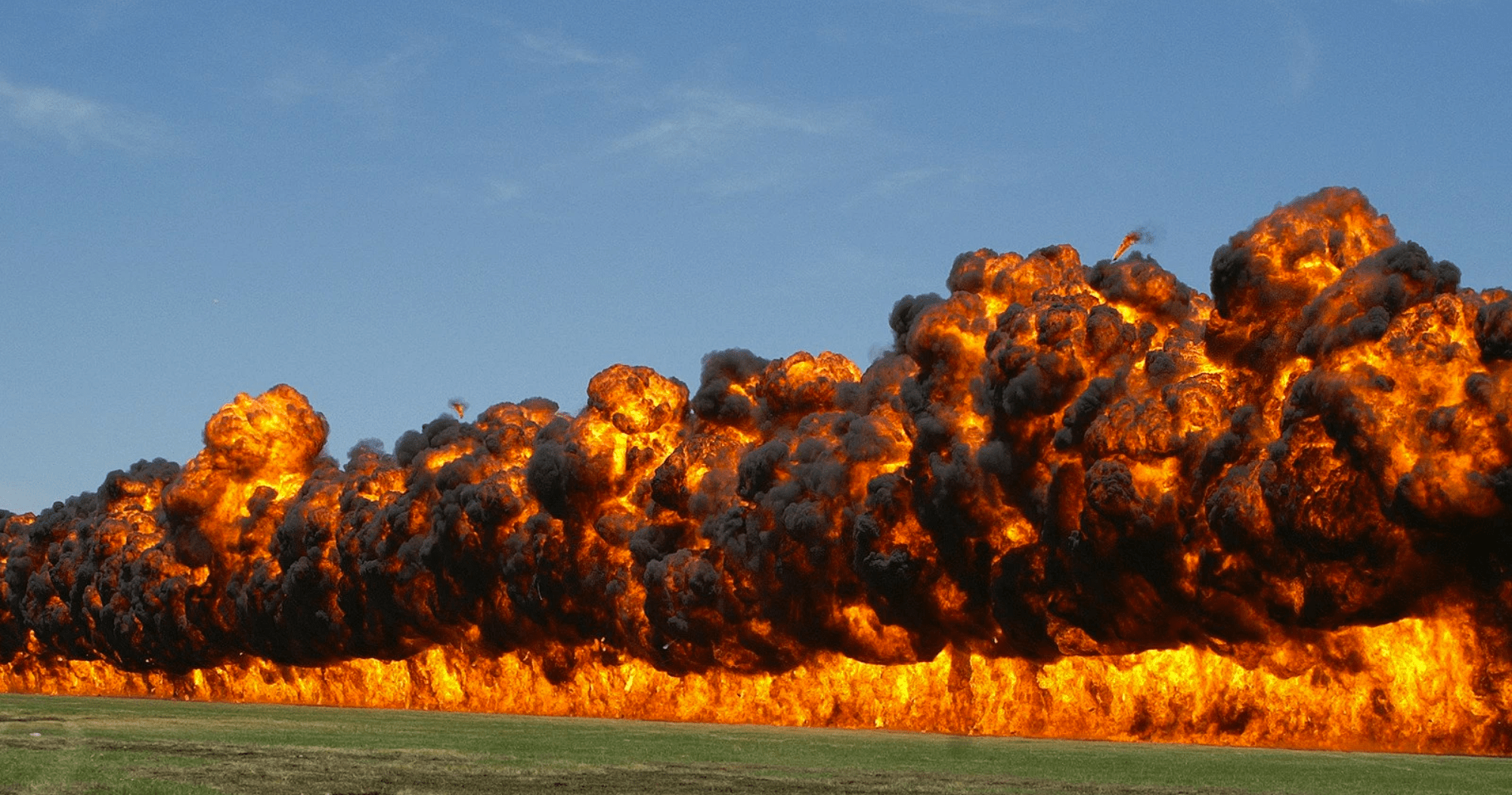

Through the debate between carpet bombing (the British) and precision bombing (the knights of the sacred U.S. mafia), Gladwell admits that the British position was driven by sadism and led by a sadist and a psychopath. These are his words, not mine. He admits that the U.S. approach failed terribly on its own terms and amounted to a delusional cult for true believers (his words). Yet we have to sit through page after page of what Holden Caulfield would have called all that David Copperfield crap. Where were each bomber mafioso’s parents from, what did they wear, how did they fart. It’s endless “humanization” of professional killers, while the book contains a total of three mentions of the Japanese victims of the triumphant arson from hell. The first mention is three sentences about how babies burned and people jumped in rivers. The second is a few words about the difficulty pilots had coping with the smell of burning flesh. The third is a guess at the number killed.

Even before he falls from Heaven, LeMay is depicted as murdering U.S. sailors in a practice exercise bombing a U.S. ship off the West Coast. There’s not a word about LeMay or Gladwell considering this a problem.

Much of the book is a build-up to LeMay’s decision to save the day by burning a million people. Gladwell opens this key section by claiming that humans have always waged war, which simply isn’t true. Human societies have gone millennia without anything resembling war. And nothing resembling current war existed in any human society more than a relative split second ago in terms of the existence of humanity. But war must be normal, and the possibility of not having it must be off the table, if you are going to discuss the most humani-satan-arian tactics for winning it *and* pose as a moralist.

The British were sadistic, of course, whereas the Americans were being hard-nosed and practical. This notion is possible, because Gladwell not only doesn’t quote or provide the name of or the cute little backstory for a single Japanese person, but he also doesn’t quote anything a single American said about the Japanese people — other than how they smelled when burning. Yet the U.S. military invented sticky burning gel, then built a fake Japanese city in Utah, then dropped the sticky gel on the city and watched it burn, then did the same thing to real Japanese cities while U.S. media outlets proposed destroying Japan, U.S. commanders said that after the war Japanese would be spoken only in hell, and U.S. soldiers mailed the bones of Japanese soldiers home to their girlfriends.

Gladwell improves on the supposed mental state of his reluctant bomber devils by inventing it, guessing at what they thought, putting words in the mouths even of people from whom many actual words are documented. He also quotes but brushes quickly past LeMay telling a reporter why he burned Tokyo. LeMay said he’d lose his job like the guy before him if he didn’t quickly do something, and that was what he could do. Systemic momentum: a real problem that is exacerbated by books like this one.

But mostly Gladwell glues morality onto his portrait of LeMay by eliminating the Japanese even more effectively than did the Napalm. In a typical passage like some others in the book, Gladwell quotes LeMay’s daughter as claiming that her father cared about the morality of what he was doing because he stood on the runway counting the planes before they took off to bomb Japan. He cared how many would come back. But there weren’t any Japanese victims on his runway — or in Gladwell’s book for that matter.

Gladwell praises LeMay’s behavior as more truly moral and having benefitted the world, while claiming that we admire Hansell’s morality because we can’t really help ourselves, whereas it’s a sort of Nietzschean and audacious immorality that we actually need, even if — according to Gladwell — it ends up being the most moral action in the end. But was it?

The traditional story ignores the firebombing of all the cities and jumps straight to the nuking of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, falsely claiming that Japan was not yet ready to surrender and that the nukes (or at least one of them and let’s not be sticklers about that second one) saved lives. That traditional story is bunk. But Gladwell is trying to replace it with a very similar story given a fresh coat of weaponized paint. In Gladwell’s version it was the months of burning down city after city that saved lives and ended the war and did the hard but proper thing, not the nuclear bombs.

Of course, as noted, there’s not one word about the possibility of having refrained from a decades long arms race with Japan, having chosen not to build up colonies and bases and threats and sanctions. Gladwell mentions in passing a guy named Claire Chennault, but not one word about how he helped the Chinese against the Japanese prior to Pearl Harbor — much less about how his widow helped Richard Nixon prevent peace in Vietnam (the war on Vietnam and many other wars not really existing in Gladwell’s leap from Satan winning the battle of WWII to Jesus winning the war for precision philanthropic bombings).

Any war can be avoided. Every war takes great efforts to begin. Any war can be halted. We can’t say exactly what would have worked. We can say that nothing was tried. We can say that the drive by the U.S. government to speed up the end of the war with Japan was driven largely by the desire to end it before the Soviet Union stepped in and ended it. We can say that the people who went to prison in the United States rather than take part in WWII, some of whom launched the Civil Rights movement of the coming decades from within those prison cells, would make more admirable characters than Gladwell’s beloved pyromaniacal chemists and cigar-chomping butchers.

On one thing Gladwell is right: people — including bombing mafiosi — cling fiercely to their faiths. The faith Western writers hold most dear may be the faith in World War II. As the nuclear bombings propaganda runs into trouble, we should not be shocked that someone produced this disgusting piece of murder romanticization as a backup narrative.