By Leila Marcovici and Pat Elder, November 16, 2020

From Military Poisons

In September 2020, the Maryland Department of the Environment (MDE) released a report entitled “St. Mary’s River Pilot Study of PFAS Occurrence in Surface Water and Oysters.” (PFAS Pilot Study) that analyzed the levels of per-and poly fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in seawater and oysters. Specifically, the PFAS Pilot Study concluded that although PFAS is present in tidal waters of the St. Mary’s River, the concentrations are “significantly below risk based recreational use screening criteria and oyster consumption site-specific screening criteria.”

While the report makes these broad conclusions, the analytical methods and basis for the screening criteria used by MDE are questionable, resulting in a misleading of the public, and providing a deceptive and false sense of safety.

PFAS are a family of toxic and persistent chemicals found in industrial products. They are worrisome for a number of reasons. These so-called “forever chemicals” are toxic, do not break down in the environment, and bio-accumulate in the food chain. One of the over 6,000 PFAS chemicals is PFOA, formerly used to make DuPont’s Teflon, and PFOS, formerly in 3M’s Scotchgard and firefighting foam. PFOA has been phased out in the U.S., although they remain widespread in drinking water. They have been linked to cancer, birth defects, thyroid disease, weakened childhood immunity and other health problems. PFAS are individually analyzed in the parts per trillion rather than in the parts per billion, like other toxins, which can make the detection of these compounds tricky.

The MDE’s conclusion over-reaches the reasonable findings based on the actual data collected and falls short of acceptable scientific and industry standards on several fronts.

Oyster Sampling

One study performed and reported in the PFAS Pilot Study tested and reported on the presence of PFAS in oyster tissue. The analysis was performed by Alpha Analytical Laboratory of Mansfield, Massachusetts.

The tests performed by Alpha Analytical Laboratory had a detection limit for oysters at one microgram per kilogram (1 µg/kg) which is equivalent to 1 part per billion, or 1,000 parts per trillion. (ppt.) Consequently, as each PFAS compound is detected individually, the analytical method employed was unable to detect any one PFAS present at an amount of less than 1,000 parts per trillion. The presence of PFAS is additive; thus the amounts of each compound are appropriately added to arrive at the total PFAS present in a sample.

Analytical methods for detecting PFAS chemicals are advancing rapidly. The Environmental Working Group (EWG) took tap water samples from 44 locations in 31 states last year and reported results in the tenths per trillion. For instance, the water in New Brunswick, NC contained 185.9 ppt of PFAS.

The Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, (PEER) (specifics shown below) has used analytical methods able to detect ranges of PFAS in concentrations as low as 200 – 600 ppt, and Eurofins has developed analytical methods having a detection limit of 0.18 ng/g PFAS (180 ppt) in crab and fish and 0.20 ng/g PFAS (200 ppt) in oyster. (Eurofins Lancaster Laboratories Env, LLC, Analytical Report, for PEER, Client Project/Site: St Mary’s 10/29/2020)

Accordingly, one has to wonder why MDE hired Alpha Analytical to manage the PFAS study if the detection limits of the methods used were so high.

Because the detection limits of the tests performed by Alpha Analytical are so high, the results for each individual PFAS in the oyster samples were “Non-Detect” (ND). At least 14 PFAS were tested in each sample of oyster tissue, and the result for each was reported as ND. Some samples were tested for 36 different PFAS, all of which reported ND. However, ND does not mean that there is no PFAS and/or that there was no health risk. MDE then reports that the sum of 14 or 36 ND is 0.00. This is a misrepresentation of the truth. Because PFAS concentrations are additive as they relate to public health, clearly then the addition of 14 concentrations just below the detection limit could equal an amount well above a safe level. Accordingly, a blanket statement that there is no danger to public health based on the finding of “non-detect” when the presence of PFAS in the water is indisputably known, is simply not complete or responsible.

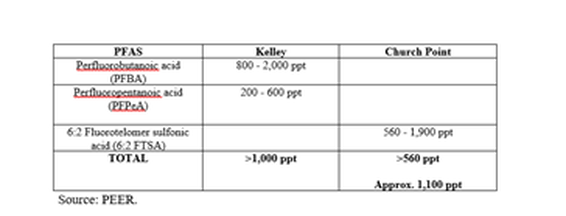

In September, 2020 Eurofins – commissioned by the St. Mary’s River Watershed Association and financially supported by PEER- tested oysters from the St. Mary’s River and St. Inigoes Creek. Oysters in the St. Mary’s River, specifically taken from Church Point, and in St. Inigoes Creek, specifically taken from Kelley, were found to contain more than 1,000 parts per trillion (ppt). Perfluorobutanoic acid (PFBA) and Perfluoropentanoic acid (PFPeA) were detected in the Kelley oysters, while 6:2 Fluorotelomer sulfonic acid (6:2 FTSA) was detected in the Church Point oyster. Because of the low levels of PFAS, the exact amount of each PFAS was difficult to calculate but a range of each was calculable as follows:

Interestingly, MDE did not consistently test the oyster samples for the same set of PFAS. MDE tested oyster tissue and liquor from 10 samples. Tables 7 and 8 of the PFAS Pilot Study show that 6 of the samples were not analyzed for PFBA, PRPeA, or 6:2 FTSA (the same compound as 1H,1H,2H,2H- Perfluorooctanesulfonic Acid (6:2FTS)), while four of the samples were tested for these three compounds returning findings of “Non Detect.” The PFAS Pilot Study is devoid of any explanation as to why some oyster samples were tested for these PFAS while other samples were not. The MDE reports that PFAS was detected at low concentrations throughout the study area and concentrations were reported at or near the method detection limits. Clearly, the detection limits of the methods employed by the Alpha Analytical study were too high considering that Perfluoropentanoic acid (PFPeA) was found between 200 and 600 parts per trillion in oysters in the PEER study, while it was not detected in the Alpha Analytical study.

Water Surface Testing

The PFAS Pilot Study also reported on the results of testing water surface for PFAS. In addition, a concerned citizen and author of this article, Pat Elder from St. Inigoes Creek, worked with University of Michigan’s Biological Station to conduct water surface testing in the same waters in February, 2020. The following chart shows the levels of 14 PFAS analytes in water samples as reported by U.M. and by MDE.

Mouth of St. Inigoes Creek Kennedy Bar – North Shore

| U.M. | MDE | |

| Analyte | ppt | ppt |

| PFOS | 1544.4 | ND |

| PFNA | 131.6 | ND |

| PFDA | 90.0 | ND |

| PFBS | 38.5 | ND |

| PFUnA | 27.9 | ND |

| PFOA | 21.7 | 2.10 |

| PFHxS | 13.5 | ND |

| N-EtFOSAA | 8.8 | Not Analyzed |

| PFHxA | 7.1 | 2.23 |

| PFHpA | 4.0 | ND |

| N-MeFOSAA | 4.5 | ND |

| PFDoA | 2.4 | ND |

| PFTrDA BRL | <2 | ND |

| PFTA BRL | <2 | ND |

| Total | 1894.3 | 4.33 |

ND – No Detection

<2 – Below detection limit

The UM analysis found a total of 1,894.3 ppt in the water, while the MDE samples totaled 4.33 ppt, though as shown above a majority of analytes were found by MDE to be ND. Most strikingly, the UM results showed 1,544.4 ppt of PFOS while the MDE tests reported “No Detection.” Ten PFAS chemicals detected by UM came back as “No Detection” or were not analyzed by MDE. This comparison directs one to the obvious question of “why;” why is one laboratory unable to detect the PFAS in the water while another is able to do so? This is only one of the many questions raised by the MDE results.The PFAS Pilot Study claims to have developed “risk-based surface water and oyster tissue screening criteria” for two kinds of PFAS – Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) and Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS). MDE’s conclusions are based on the sum of just two compounds – PFOA + PFOS.

Again, the report is devoid of any explanation as to why only these two compounds were selected in its screening criteria, and as to the meaning of the term “risk-based surface water and oyster tissue screening criteria.”

Thus, the public is left with another glaring question: why is MDE limiting its conclusion to only these two compounds when many more have been detected, and many more are able to be detected when using a method having a lower minimum detection limit?

There are gaps in the methodology used by MDE in rendering its conclusions, and also inconsistencies in and lack of explanation as to why differing PFAS compounds are tested between samples and throughout the experiments. The report does not explain why certain samples where not analyzed for more or fewer compounds than other samples.

The MDE concludes, “surface water recreational exposure risk estimates were significantly below MDE site-specific surface water recreational use screening criteria,” but provides no clear description of what this screening criteria entails. This is not defined and thus cannot be assessed. If it is an adequate scientific-based method, the methodology should be presented and explained citing scientific basis.Without adequate testing, including defined and explained methodology, and employing tests that are able to assess concentrations at the low levels required for such analysis, the so-called conclusions offer little guidance that can be trusted by the public.

Leila Kaplus Marcovici, Esq. is a practicing patent attorney and volunteers with the Sierra Club, New Jersey Chapter. Pat Elder is an environmental activist in St. Mary’s City, MD and volunteers with the Sierra Club’s National Toxics Team