by Taylor Barnes, Responsible Statecraft, July 23, 2021

This article was co-published with Facing South.

On a warm Saturday morning in May, a group of demonstrators gathered in a public square in Asheville, North Carolina, for the kind of protest lawmakers don’t usually foresee when they haggle for a share of the United States’ massive military budget to be spent in their home districts. The environmentalists, anti-war veterans, and economic justice advocates go by the name Reject Raytheon AVL, a reference to Massachusetts-based Raytheon Technologies, the world’s second-largest weapons maker. A division of the company, Pratt & Whitney, is building a new engine parts plant in their city, and the protesters oppose the millions of dollars in subsidies their county and state governments have committed to Raytheon, arguing the money should instead support green jobs.

The protesters, including about 50 people and three dogs, marched nine miles to the future plant site — an unusually vibrant display of local resistance to the decades-old sales pitch that undergirds the U.S. military-industrial complex in communities nationwide: that ethics and profligate public spending should be overlooked in exchange for producing jobs.

“I’m tired of the attempts to shut us down by telling us we should be grateful for any job they graciously offer,” Jenny Andry, a local teacher, said at a rally along the march route. “Those climbing into bed with the military-industrial complex parrot over and over again textbook justifications for harmful projects like this one.”

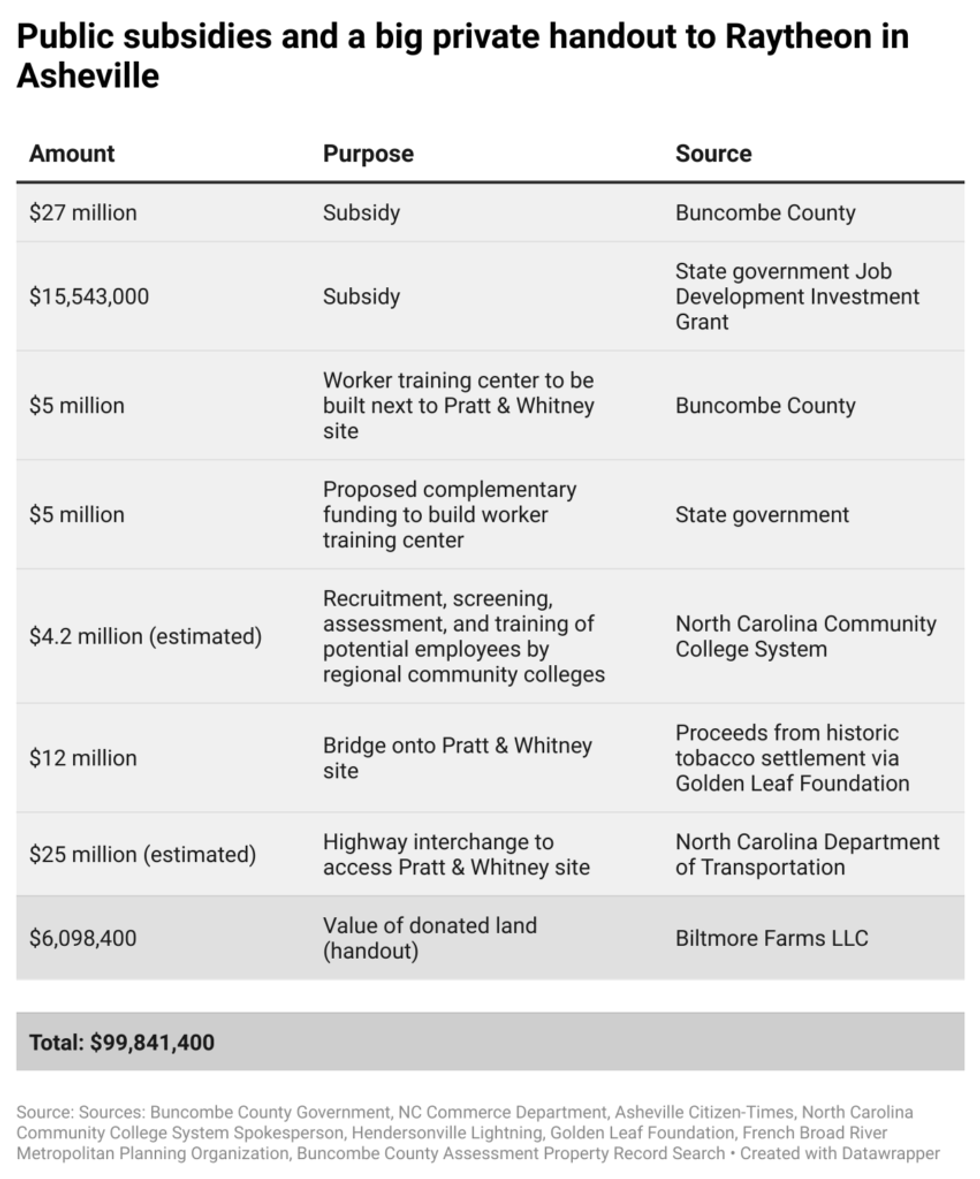

Reject Raytheon AVL’s outrage had grown in recent weeks, as the Israeli Defense Forces had used F-35 fighter jets — to which the Asheville plant will contribute parts — in a devastating bombing campaign over the Gaza Strip that left 256 people dead, including more than 100 women and children, while 12 people, including two children, were killed in Israel during the hostilities. Meanwhile, officials in Buncombe County, where Asheville is the seat, had approved yet another subsidy for the Raytheon plant, this time for construction of a worker training center near the plant site, part of a growing package of handouts from officials and a private landowner that is nearing $100 million in value, according to calculations by Responsible Statecraft and Facing South.

The deal may ultimately be less about creating jobs than moving them: A union in Connecticut, where Pratt & Whitney is based and whose members perform jobs similar to those slated for Asheville, warned that the new plant may cause layoffs at theirs.

While boosters of the subsidies claim they will bring 800 jobs with middle-class wages, an analysis by Responsible Statecraft and Facing South found problems with that promise, including a potential loss of hundreds of jobs after a decade, a skewed representation of wages that may inflate the amount that workers can expect to earn, and confidentiality provisions that have hidden whether similar deals elsewhere have delivered on job creation claims. And the deal may ultimately be less about creating jobs than moving them: A union in Connecticut, where Pratt & Whitney is based and whose members perform jobs similar to those slated for Asheville, warned that the new plant may cause layoffs at theirs. Protestors say this isn’t the kind of company that deserves a sweetheart deal from local government.

County and economic development officials also signed non-disclosure agreements when negotiating the subsidies package, and the resulting secrecy favors corporations and makes outcomes harder to evaluate. Documentation obtained by Responsible Statecraft and Facing South shows that a neighboring county’s incentives package for a solar equipment manufacturer that pays similar wages, signed around the time the Raytheon deal went through, spent far less to attract each job and appears to include stronger job protections.

The Asheville Raytheon deal highlights the entrenchment of the military-industrial complex in the U.S. landscape through the creation of so-called defense communities that rely on military spending for their economic well-being. The United States spends half of its federal discretionary budget on the military, crowding out other areas it could choose to prioritize, like public health, education, and diplomacy. Its military budget is more than the next top 10 militaries combined. The F-35, a fighter jet in the works for two decades that has been plagued with defects, has become an emblem of military-industrial complex excess. Its projected cost has ballooned to $1.7 trillion, making it the most expensive weapons program in U.S. history, even while it had accumulated some 871 documented design flaws as of January 2021. Rep. Adam Smith, chair of the House Armed Services Committee, recently called the F-35 a “rathole” for taxpayer money and suggested the government “cut our losses.”

Greater investment in North Carolina’s burgeoning solar sector is a clear alternative to spending public money to create military-related jobs. North Carolina ranks second in the nation for solar generation, and there is much room to grow: According to the federal Energy Information Administration, solar power provided only about 6 percent of the state’s generation in 2019, and North Carolina consumes nearly four times more energy than it produces. The EIA also noted that the state’s Atlantic coast could be conducive to offshore wind farms. Last year, the same Buncombe County government that approved Raytheon subsidies also approved a project to install on-site solar energy on about 45 public buildings, the largest solar project ever developed by a local government in North Carolina. Fearing the new plant will hold back their hometown’s green transition by anchoring it in the war economy, Asheville activists are sounding the alarm on the “expansion and enrichment of the military-industrial complex,” in the words of rally-goer Said Abdallah.

“We just don’t want this poison in our county,” he said.

A race to the bottom

For a deal that involves so many thorny issues about arms sales, job creation, and local government budgets, the Asheville public had only one hour last November to offer its input.

The deal had been in the works since the spring of 2019, when a North Carolina delegation traveled to the Paris Air Show to meet with Pratt & Whitney officials, according to a detailed report in the Hendersonville Lightning. In Asheville, meanwhile, Biltmore Farms LLC, a company headed by local landowner and Vanderbilt family descendent John “Jack” Cecil, told economic development authorities that the firm was eager to turn vast tracts of forested land at the base of the Blue Ridge Mountains into an industrial park.

As the conversations moved forward, county and economic development officials were required to sign non-disclosure agreements, something that Commissioner Al Whitesides would later say was necessary because publicity can cause landowners to raise their prices for prospective new businesses. But Biltmore Farms donated 100 acres to Raytheon for $1, with the value of the land expected to increase dramatically due to publicly-funded infrastructure upgrades.

The use of NDAs to negotiate economic incentive deals to attract major firms like Raytheon, a Fortune 100 company, is “super routine, and it’s just outright corruption,” said Pat Garofalo, the author of “The Billionaire Boondoggle: How Our Politicians Let Corporations and Bigwigs Steal Our Money and Jobs” and the director of state and local policy at the anti-monopoly American Economic Liberties Project.

Lawmakers in at least two jurisdictions, New York City and Illinois, have proposed legislation to ban the use of NDAs in economic development because they contribute to a race to the bottom as localities compete against each other to snag new business opportunities. “These deals are often designed to be done quickly and in secret because when the public gets more of a say, they tend to be defeated,” Garofalo said.

In Asheville, the secrecy meant that the public only found out about the deal from a press release in late October of last year, leaving them scrambling to learn more ahead of the public hearing on Nov. 17. The meeting was an awkward one, where socially distanced officials sat quietly behind daises in a dimly lit room while residents in their homes participated virtually, watching a livestream presentation on the deal by company and county officials as they waited for their turn to chime in.

When the chairman opened the meeting to the public, he gave the first nod to the uproar to come, noting that there were a “significant number of folks” who wanted to have a word.

“This will probably take a while,” he added.

And residents made sure that it did, despite having only three-minute speaking slots.

Many expressed outrage over the devastating Saudi-led war in Yemen, where investigators have found U.S.-made Raytheon weapons parts at bomb sites where civilians and children had been killed. Veronica Coit, a local hair stylist, asked the commissioners how they would feel if, in a future war, “among massacred children and civilians dying in the streets, another photojournalist finds another label, but this time it says ‘made in Asheville, North Carolina?’” Many speakers were also exasperated at what they saw as double-dipping by a company flush with federal contracts that’s also seeking public money from local governments.

“As an American taxpayer, I already share a portion of my wages with Raytheon,” said Andry, the teacher. “I vehemently oppose sharing my home with them, too.”

One participant asked if the commissioners could renegotiate a deal in which the factory made parts only for civilian aircraft, also a major part of Pratt & Whitney’s business that the plant will contribute to. But the commission intended to vote on the deal as presented before the meeting was over, so redrafting wasn’t a consideration.

Others made deeply personal appeals to elected officials’ consciences. David Pudlo, a service technician for a local solar installer, addressed Commissioner Jasmine Beach-Ferrara, a pastor and LGBTQ rights advocate running for Congress as a Democrat against Rep. Madison Cawthorn. “What would Jesus do?” Pudlo asked. “It’s pretty clear that he would not be collaborating with arms dealers.”

In all, 21 members of the public spoke out at the meeting, and all but one opposed the deal. The commissioners — six Democrats and one Republican — approved it unanimously.

Surveilling protesters?

The Pratt & Whitney plant marks a major turning point for Asheville’s economy. The $27 million incentives package signed between Raytheon and Buncombe County, structured as grants given to the company if it makes “good faith efforts” to meet job creation and investment targets, is the largest such deal the county has signed in a decade, according to a detailed list of incentive agreements the county government provided Responsible Statecraft and Facing South. The Pratt & Whitney deal represents 42 percent of all funds committed by the county to incentivize projects in that period.

Reject Raytheon AVL was created by people who met each other as disembodied voices at that first public hearing to discuss the deal. Though the meeting cemented Raytheon’s entrance into Asheville with hefty taxpayer backing, the group wanted to broadcast its disapproval while also communicating the central idea its diverse members coalesced around: that job creation is a fine goal for policymakers but there are better ways to achieve it.

Research from economist Heidi Peltier at Boston University’s Costs of War Project backs them up: According to her calculations, just about any other kind of government spending — on health care, green energy, or education — creates more jobs than weapons spending, in part because weapons are capital-intensive, meaning less money goes straight to salaries.

At a March protest at Asheville’s Chamber of Commerce, Reject Raytheon AVL members noticed a man in a black truck taking their photos.

In the months since Buncombe County approved the deal, Reject Raytheon AVL demonstrators have become a staple on Asheville’s streets, holding protests at the plant site with signs like “Honk for humane jobs” and lobbying public officials whenever they can, such as at the May meeting that approved an additional $5 million to be spent on building a worker training center for Pratt & Whitney.

The group believes its activities have come under surveillance. At a March protest at Asheville’s Chamber of Commerce, for example, Reject Raytheon AVL members noticed a man in a black truck taking their photos. They snapped a picture of his license plate and traced it back to Cody Muse, a licensed private investigator. Reached by phone, Muse responded to a description of the alleged incident by saying “I don’t talk about anything with any journalist” before hanging up. He did not respond to an additional request for comment on the allegations sent via LinkedIn.

Then in April, Ken Jones, a retired professor and Veterans for Peace associate who has participated in the protests, was walking on the future plant site when he saw a security guard who appeared to be filming him. Jones said the guard called out to him using a full version of his first name, Kenneth, and a middle name he does not use publicly. The incident led him to suspect that the guard had used facial recognition technology to identify him in a database.

Neither Biltmore Farms LLC, the company that donated land to Raytheon, nor spokespeople for Pratt & Whitney responded to numerous requests for comment on whether they hired Muse or employed such surveillance technology against the protesters.

The incidents rattled but also reinvigorated the activists, who see their campaign as one that will likely extend for years. They join other underdog grassroots movements across the heavily militarized South — the region that contributes the most recruits to the armed forces relative to its population and is home to the largest U.S. military base at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. In Huntsville, Alabama, a hub for defense contractors known as “the Pentagon of the South,” anti-war activists have staked out a weekly “Peace Corner” for nearly two decades. In Texas, a state that ranks third in military spending, a group of women students in Austin recently wrote a report detailing weapons makers in the University of Texas system’s endowment and lobbied for the student government to pass a divestment resolution. The campaign prompted a counter-petition by more than 150 other UT students, mostly in engineering, who said the resolution would jeopardize their job prospects with military contractors.

At the Raytheon protest march held in Asheville in May, demonstrators were mostly met with supportive car horn beeps and passengers eagerly taking their pamphlets, though a few threw up their middle fingers and one driver yelled, “You idiots!” Bob Brown, a janitor and Vietnam draftee who carried a large Veterans for Peace flag, was encouraged by what he saw as the increasing momentum of anti-war activism he had been engaged in for five decades. “This movement is truly something new,” he said. “I’ve been doing this since the Vietnam years, and we’ve never seen so much public support.”

Questioning ‘good faith efforts’

At the heart of the uproar in Asheville is what the deal’s boosters have advertised as 800 jobs with an average salary of $68,000. Tourism is a major industry in the city, where the Blue Ridge Mountains provide a popular setting for destination weddings, outdoor sports, and vacations. But service jobs in the hospitality industry do not offer the wages found in aerospace and defense. Peltier, the Boston University economist, calls the disparity a “wage premium” made possible by ample government funding that helps military contractors pay better than civilian employers.

In a twist peculiar to Asheville, a blue dot in a red district that voted for Donald Trump, even some members of the overwhelmingly Democratic county commission say they share the protesters’ fundamental concerns about U.S. involvement in overseas wars and its outsized military budget.

“I left a picket line one day and I was on active duty in the Navy two weeks later,” Commissioner Whitesides said at the November meeting, recalling his younger years. The civil rights activist, banker, and Vietnam veteran is the commission’s only Black member, and he said the deep racial wealth gap in Asheville and the need to make what he calls a “generational change” to upgrade the local employment market led him to support the Raytheon deal.

“Like all of you here, I have wrestled with this,” Whitesides said, “but I weighed it against what’s going to be best for our community, what’s going to be the best for your kids.”

But a close examination of the deal suggests that the majority of the company’s workers will be earning far less than the average wage. It also suggests that the advertised 800 jobs — if they ever reach that number — may decline quickly.

The agreement signed between Buncombe County and Pratt & Whitney refers to the company using “good faith efforts” to build up to an eventual 750 cumulative jobs during an “incentive period” between 2021 and 2029, with an additional bonus paid out if they create 50 more. After 2029, the number of “retained” jobs then drops to 525 for a four-year period.

In response to questions from Responsible Statecraft and Facing South, Tim Love, the director of intergovernmental affairs for Buncombe County, denied that the discrepancy between the numbers meant that the deal included as many as 275 temporary construction jobs. County Commission Chair Brownie Newman said the lower number in 2030 is because “the further you go out into the future, the less certainty there is in planning for business operations.” Newman also insisted that the language of “good faith efforts” would not get the company off the hook for job creation targets, and that incentive payouts will be adjusted downward if it comes up short. Garofalo, the author of the book critical of economic development deals, said the abrupt drop in job numbers in 2030 looks “like license to lay off.” Pratt & Whitney did not respond to multiple phone and email requests for comment on its job creation projections.

As to workers’ wages, the agreement requires Pratt & Whitney to pay an average of $68,000 to its plant employees. But averages can be skewed by a handful of high salaries at the top, so examining median wages instead — lining up workers in order of pay and looking at the one in the middle — would better reflect how a project affects rank-and-file workers. That’s especially critical in the defense industry, since research by Stephen Semler at the Security Policy Reform Institute shows that wide pay disparity is routine at defense contractors like Raytheon, whose CEO made 282 times as much as its median worker in 2019.

A wage chart presented at the November meeting marked “for illustrative purposes only” suggests that the median salary at the plant would be $55,000. But Kevin Kimrey, the director of economic and workforce development at Asheville-Buncombe Technical Community College, which is partnering with the defense contractor to train workers, told the Asheville Citizen-Times that machinists and skilled floor laborers may earn just $40,000 to $50,000 a year. That’s below Buncombe County’s median household income of just over $52,000, while a parent of two earning $43,920 in North Carolina is eligible for food assistance.

If the project’s salaries turn out to be lower than promised, it wouldn’t be for lack of public investment. When the agreement was first announced, it came with subsidies of $27 million from the county and an additional $15.5 million from the state. But in the months since, more public subsidies have crept into the deal via funds channeled through the community college system and infrastructure projects to support the plant. A first-of-its-kind tally by Responsible Statecraft and Facing South puts the total value of those estimated subsidies and handouts at nearly $100 million.

That estimate suggests that each of the 525 “retained” jobs — the ones that appear to be the intended legacy of the project — is being subsidized in the amount of $190,174.09.

Responding to the tally of subsidies, Newman said some of the infrastructure projects would be useful to the community whether or not Pratt & Whitney came to town, such as the worker training facility, which will be owned by the county government, and the highway interchange, which he called “a worthwhile transportation investment regardless of its value to the Pratt manufacturing facility.” But official documents for both projects identify Pratt & Whitney as the sole beneficiary.

Another beneficiary may end up being Biltmore Farms, which donated land to Raytheon but still has hundreds of acres more available that could be sold to other manufacturers for an eventual industrial park. Asked if Biltmore Farms would be expected to donate land to any future clients or if it could profit from the sale of tracts increased in value due to publicly funded infrastructure upgrades, Newman said that he could not speculate on a private firm’s dealings. But he added in an email that his “general sense is that they considered it a sound business decision to donate the 100+ acres of land for the Pratt project with the belief that the donated value can be recouped from other projects that may move forward in the future once the infrastructure improvements are made in the area.”

Responsible Statecraft and Facing South sought documentation from two other local governments that offered incentives agreements to Pratt & Whitney in recent years to see if their job creation goals were met. In Georgia, where the government announced in 2017 that Pratt & Whitney would create 500 new jobs at its Columbus facility in a deal involving about $34 million in local tax breaks, Suzanne Widenhouse, chief appraiser at the Muscogee County Board of Assessors, said she could not share certification letters on the company’s performance with the public because they are considered confidential under Georgia law. However, Widenhouse did provide a blank copy of the form the company is required to submit to the local government — a single page that requires the company to report little more than how much it spent on property and equipment and the number of employees.

In Orange County, New York, where Pratt & Whitney announced in 2014 that it would create 100 jobs over five years and retain 95 existing ones at a subsidiary with help from an incentives package including a potential local sales tax abatement, Bill Fioravanti, the local director of economic development, referred Responsible Statecraft and Facing South to a company spokesperson for information on current employment levels. The spokesperson did not respond to multiple emailed requests.

Regarding the new Asheville plant, Love, the Buncombe County official, told Responsible Statecraft and Facing South that confirmation letters on job creation targets will be made publicly available. Remarkably, Love told the November meeting that the county doesn’t expect a “breakeven” point until year 12 in its 14-year agreement with Pratt & Whitney, a projection he said is “based on economic factors” since Pratt “has to hit their targets” and the economy “has to stay on track.” When Newman was asked if that breakeven point was a good deal for the county, he said that after year 12 it is likely that “the facility will continue to operate and make very large property tax payments.”

National disease, local resistance

Comments Raytheon CEO Greg Hayes made in a call with investors last October suggest the North Carolina plant may be moving jobs out of other locations. He said the company expects to save $175 million annually once the Asheville plant is up and running, that it will be more “automated,” and that “some of it will involve moving work from high-cost to lower-cost locations.” A relocation specialist not affiliated with the project estimated for the Asheville Citizen-Times that labor costs are 15 to 20 percent lower in North Carolina than in Connecticut; those savings are due in part to North Carolina’s “right-to-work” laws that make unionization difficult. In Connecticut, where Pratt & Whitney is headquartered, the local chapter of the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers, which represents workers at the company, sent an alarmed letter to its members after news of the Asheville plant broke. The union noted that the North Carolina site is slated to begin production in 2022 — the same year that the unionized workers in Connecticut will renegotiate their contracts.

“Start putting money away now so you are prepared,” the union told its members. “[H]istory has not shown Pratt & Whitney to be a company that has had the best interest of its Connecticut work force in mind as it moved work that used to be done here all over the globe.” A union representative declined to elaborate on the letter ahead of the coming negotiations.

In Asheville, no one debating the deal disputes that the city needs better-paying jobs. But Andry, the teacher, said Reject Raytheon AVL’s fight over the plant boils down to a belief that “not all jobs are created equal.” Members of the group are now discussing the possibility of organizing workers at the future Asheville plant.

As a possible alternative to Raytheon, Anne Craig, a 2017 recipient of a peacemaker award offered by local civic groups, pointed out that neighboring Henderson County attracted an innovative solar equipment manufacturer a month after Buncombe County approved the Raytheon plan. That deal, which will make use of an existing warehouse, projects 60 jobs created over five years at an average salary of $65,000. A copy of the incentives agreement obtained by Responsible Statecraft and Facing South from the county attorney shows a deal with better labor protections than the one with Raytheon. The agreement includes no language about “good faith efforts” and simply requires the company to meet job creation targets in order to receive reimbursements from the county, which come in at a modest total of $114,404.93. (Read more below about how investing in North Carolina’s emerging solar power industry can serve as an alternative model to efforts to bring defense industry jobs.)

The protesters have also suggested using the public funds instead to honor another pledge the city and county recently made, which could also create new jobs. Following last year’s Black Lives Matter uprisings, Asheville became one of a handful of cities across the country to pass a resolution supporting reparations for slavery, a motion also approved by Buncombe County. Asheville’s Racial Justice Coalition, which promoted the motion, has called for $4 million — a tiny fraction of the public money slated to be spent at Pratt & Whitney site — to fund initiatives covered in the resolution, such as affordable housing. Such a move would not only address a historic debt and provide a tangible good for the community but could also be a job creator. Peltier, the economist, calculated for Responsible Statecraft and Facing South that $4 million spent to construct multi-unit affordable housing would create about 64 direct, indirect, and induced jobs.

Perhaps no public official in Asheville has more publicly reckoned with the Raytheon deal than County Commission Chair Newman, a solar energy entrepreneur who backs the reparations resolutions. He calls the climate crisis his “highest priority as an elected official” and has repeatedly said he shares the public’s fundamental concerns about endless wars. However, he argues that the location of such a facility ultimately “does not have any bearing on how our country handles such important foreign policy concerns” and policy actions made at the federal level. “If I thought the decisions made by our local government would have a direct bearing on those issues, I would think about it differently,” he declared during the public meeting in November.

But Dan Grazier, a Marine veteran and Pentagon watchdog at the Project on Government Oversight, said that “political engineering” by defense contractors is a crucial ingredient in the intractability of wasteful weapons programs in general and the F-35 in particular. He recalled a 2017 Capitol Hill marketing event that he slipped into where Lockheed Martin, the F-35’s prime contractor, had invited congressional staffers to test out an F-35 cockpit simulator while enjoying a continental breakfast. Grazier noticed the company had laid out promotional literature on a table that included a map showing how many jobs it claims are tied to the fighter jet’s production in each of the states they represent.

Lawmakers in recent years have become increasingly emboldened to take on the military budget. Last year, for example, an unprecedented 116 U.S. House and Senate members voted to cut it by 10 percent. But the struggle to rein in the Pentagon budget is thwarted by economic dependency. Should Buncombe County Commissioner Beach-Ferrara, the pastor and LGBTQ rights advocate, win her congressional race, she would be thrust into that debate while representing a district newly reliant on Raytheon for hundreds of jobs. Beach-Ferrara did not respond to a voicemail and emails requesting an interview for this story.

“You gotta hand it to the defense industry and the military-industrial-congressional complex in figuring all this out,” said Grazier. “Because by spreading all these contracts all over the United States for the F-35, they created hundreds and hundreds of political fighters on Capitol Hill that are going to do a lot to defend this program, no matter how it performs.”

“I don’t think any of us really believes we are going to stop this plant, but it’s a local resistance to the national disease.”

At the end of their nine-mile march back in May, the Reject Raytheon AVL demonstrators traipsed through a grassy shoulder alongside a busy road, ending in a pit of red clay where a black construction crane towered above them. The disturbed soil was the beginning of a future bridge to the Pratt & Whitney site, funded by the proceeds of a historic 1999 settlement between the North Carolina government and tobacco companies. The money, funneled through the state’s Golden Leaf Foundation, is supposed to be used to wean local economies off the harmful cigarette industry. Approaching the partially constructed bridge, Steve Norris, a great-great-grandfather wearing a traditional Middle Eastern keffiyeh scarf, said he’s empathetic to the locals hoping to get hired there. He also acknowledged that the public had learned of this project far too late to have prevented it.

“I don’t think any of us really believes we are going to stop this plant,” he said, “but it’s a local resistance to the national disease.”

This story was supported by the Sidney Hillman Foundation.