By Sean McElwee, Brian Schaffner and Jesse Rhodes, The Nation.

As the influence of high-dollar donors grows, so too will our bellicosity.

Since Donald Trump’s ascension to the presidency Washington has struggled to get a handle on his administration’s approach to matters of war and peace. In recent weeks, there has been intense focus on the perceived influence of top presidential aide Steve Bannon, who is seen as extremely hawkish on national security matters, especially when it comes to combating Islamic terrorism and confronting China’s rising influence. The prevailing wisdom seems to be that Bannon’s prominence within the administration – highlighted by his appointment to the National Security Council – portends a more bellicose turn in American national security policy.

And despite his purported skepticism of defense spending and aversion to spending cuts, Trump’s new budget bolsters spending for defense by $54 billion while cutting spending elsewhere.

There are undeniable reasons for concern – if not outright fear – about Bannon’s appointment, particularly coupled with soaring military investment. But these worries obscure more systematic – if also more subtle – reasons for the United States’ persistent aggressiveness on the world stage. (After all, American military interventionism long preceded the Trump Administration and continued during the presidency of Barack Obama). Our research suggests that a major, if under-appreciated, base of support for the frequent use of American military force abroad is the enthusiasm of wealthy persons – and especially large political donors.

On several key questions, wealthy people – and, in particular, “elite donors” (those who contribute $5,000 or more, or the top 1 percent of all donors) – are much more enthusiastic about the projection of American force than are American adults. The enthusiasm of the most wealthy and influential private actors in American politics provides a durable reservoir of support for the assertion of American power abroad. Given the profound, and likely growing, influence of political donors in American politics, our findings suggest that strong political supports for American foreign interventionism will remain long after Bannon, and Trump, have departed the executive branch.

These conclusions come from our ongoing research project on the preferences and contribution patterns of big donors. As part of this work, we investigated how preferences toward American military spending and the use of force compared between elite donors, wealthy individuals (those with family incomes of more than $150,000), all donors, and all American adults.

Our analysis drew on a cumulative data file from the 2008, 2010, 2012, and 2014 Cooperative Congressional Election Studies surveys. By pooling together multiple surveys, we were able to obtain an unusually large sample of these elite donors, as well as extremely large samples of several other groups: all political donors, individuals with family incomes over $150,000, and all American adults. (Across all surveys, there were 196,000 respondents.) To make the elite donor sample nationally representative, we re-weighted the sample using information from Catalist, a political data firm with information on more than 260 million adults, and the Federal Election Commission.

We also made efforts to ensure that we correctly identified large donors. While it’s unlikely that many people lie about contributing large amounts of money to campaigns — being an elite donor is not exactly a status that most people aspire to — we tried to account for this possibility by dropping from our analysis any self-identified elite donors who were not also validated registered voters. On the whole, our approach allowed us to examine the preferences of elite donors, and other groups, with a great deal of precision.

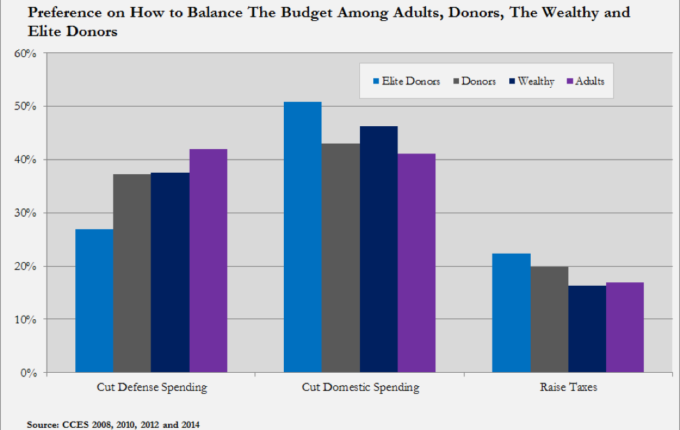

As a first observation, “elite donors” and wealthy Americans are more supportive of American military spending than are ordinary Americans. When requested to indicate whether they preferred to balance the federal budget primarily through cuts to defense spending, domestic spending cuts, or tax increases, 42 percent of American adults indicated that they preferred defense cuts. But only 25 percent of elite donors, and 36 percent of wealthy Americans, preferred that route.

We found that cutting defense spending was the most popular option for balancing the budget among ordinary Americans, but the least popular option among elite donors. And this is not simply a matter of partisanship — the “elite donors” and wealth Americans in our sample are fairly evenly divided along party lines. Further, within the parties, elite donors are more interventionist (that is, Democratic elite donors are more interventionist than non-donors and Republican elite donors are more interventionist than Republican non-donors).

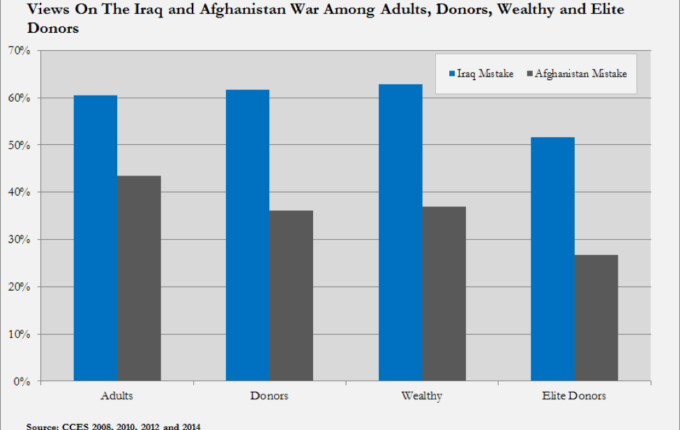

Elite donors and wealthy Americans also seem to be more sanguine about the United States’ interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan. Among all adults, 60 percent consider the United States’ involvement in Iraq a mistake. But only 52 percent of elite donors do. The opinion gap between adults and elite donors on the United States’ intervention in Afghanistan is even wider. While 43 percent of the general public consider the Afghanistan intervention a mistake, only 27 percent of elite donors do.

These findings point to the possibility that elite donors and wealthy Americans might be more favorably disposed to the use of American military force than are ordinary Americans. And, in fact, when it comes to attitudes about hypothetical military interventions, we find similar income- and donation-based effects. For example, while all of the groups in our analysis strongly support the use of American military force to protect allies under attack, elite donors and wealthy Americans are even more enthusiastic than are all American adults. Eighty-five percent of elite donors and 80 percent of wealthy Americans express support for the use of force in these circumstances, compared with 71 percent of adults.

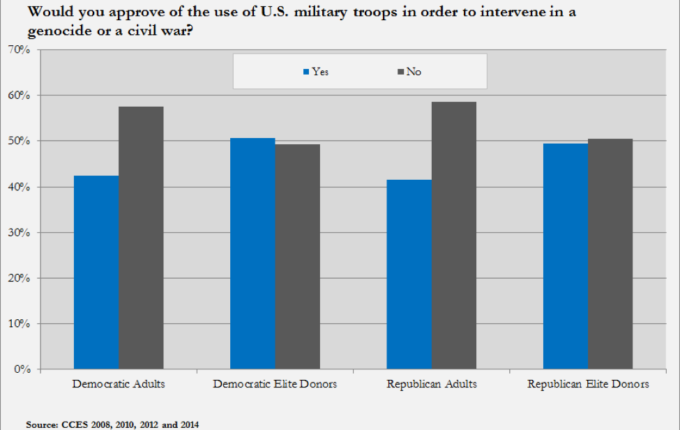

“Elite donors” and the wealthy are noticeably more likely to support a military intervention to prevent genocide (50 percent and 51 percent, respectively) compared to the general public (40 percent). And elite donors and wealthy Americans are also much more likely to express support for military interventions to destroy terrorist training camps. Sixty-four percent of American adults supported this hypothetical; but 80 percent of “elite donors” and 76 percent of wealthy Americans did.

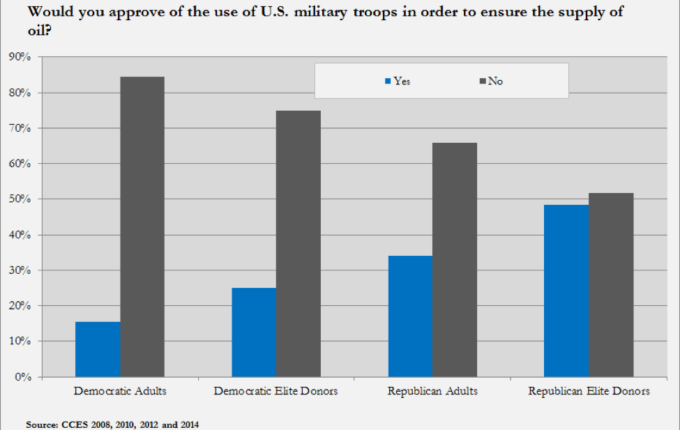

Strikingly, we found that elite donors and wealthy Americans are more likely to express support for military interventions to ensure the American oil supply. While just 25 percent of American adults expressed support for such interventions, 35 percent of elite donors did, and nearly half (48 percent) of Republican elite donors did.

These attitudinal differences matter. Recent scholarship on representation in politics strongly suggests that large donors and wealthy Americans exercise disproportionate influence on politicians, and that this bias is most notable on matters of national security and foreign policy. One reason that this might occur is that Americans feel less confident in judging debates over foreign interventions and often defer to elites on such matters, especially during conflicts.

Benjamin Page and Jason Barabas compared the foreign policy preferences of foreign policy elites using the Chicago Council on Foreign Relations surveys and found “many differences of 30, 40, and even 50 percentage points compared with the general public.” Benjamin Page and Marshall Bouton find, in their book The Foreign Policy Disconnect, that “contrary to the assertions of many scholars, pundits and political elites,” “collective public opinion about foreign policy is not inconsistent, capricious, fluctuating or unreasonable.”

Rather, they argue, the general public “generally prefers to use cooperative and multilateral means to pursue foreign policy aims.” Kull and Destler also find that elites tend to misread public opinion, and that Americans aren’t isolationist, but rather favor multilateral intervention.

Political scientists Matt Grossmann and William Isaac also found the wealthy are more likely to favor “international intervention, international institutions, foreign aid, and trade agreements.” They found that the wealthy have a disproportionate impact on foreign policy: “affluent support for foreign policy proposals without average support leads to a very high adoption rate (69 percent) compared to foreign policy proposals with only average citizen support (38 percent).”

This applies not only to a more aggressive use of force internationally, but trade policy as well, as donors are more likely to support free trade agreements. In the 2014 CCES, 68 percent of donors contributing $1,000 or more support a US-Korea free trade agreement, compared to 57 percent of the full sample.

Most of the debates about money in politics center around domestic policy: Bernie Sanders’s campaign centered around the way that millionaires and billionaires blocked the progressive agenda. However, our research suggests that elite donors have different views about the global economy and use of force overseas than the general public. Donors often give money to enact that vision, such as the millions Sheldon Adelson and Haim Saban have given to shape policy on Israel. Politicians who buck the establishment on trade and military force overseas often find themselves quickly on the defensive. Donors are likely to oppose any attempt by Trump to cloister America from the international community, but they also are unlikely to tap the brakes if he moves the country towards war.