By Thalif Deen, Inter Press Service

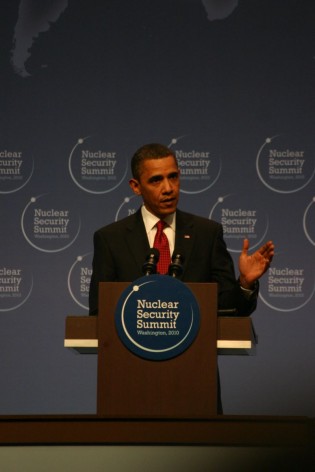

Nuclear Security has been a priority for U.S. President Barack Obama. / Credit:Eli Clifton/IPS

UNITED NATIONS, Aug 17 2016 (IPS) – As part of his nuclear legacy, US President Barack Obama is seeking a UN Security Council (UNSC) resolution aimed at banning nuclear tests worldwide.

The resolution, which is still under negotiation in the 15-member UNSC, is expected to be adopted before Obama ends his eight year presidency in January next year.

Of the 15, five are veto-wielding permanent members who are also the world’s major nuclear powers: the US, Britain, France, China and Russia.

The proposal, the first of its kind in the UNSC, has generated widespread debate among anti-nuclear campaigners and peace activists.

Joseph Gerson, Director of the Peace and Economic Security Program at American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), a Quaker organization that promotes peace with justice, told IPS there are a number of ways to look at the proposed resolution.

The Republicans in the US Senate have expressed anger that Obama is working to have the U.N. reinforce the Comprehensive (Nuclear) Test Ban Treaty (CTBT), he noted.

“They have even charged that with the resolution, he is circumventing the US constitution, which requires Senate ratification of treaties. The Republicans have opposed CTBT ratification since (former US President) Bill Clinton signed the treaty in 1996”, he added.

In fact, although international law is supposed to be U.S. law, the resolution if passed will not be recognized as having replaced the constitutional requirement of Senate ratification of treaties, and thus will not circumvent the constitutional process, Gerson pointed out.

“What the resolution will do will be to reinforce the CTBT and add a little luster to Obama’s ostensible nuclear abolitionist image,” Gerson added.

The CTBT, which was adopted by the U.N. General Assembly back in 1996, has still not come into force for one primary reason: eight key countries have either refused to sign or have held back their ratifications.

The three who have not signed – India, North Korea and Pakistan – and the five who have not ratified — the United States, China, Egypt, Iran and Israel – remain non-committal 20 years following the adoption of the treaty.

Currently, there is a voluntary moratoria on testing imposed by many nuclear-armed States. “But moratoria are no substitute for a CTBT in force. The four nuclear tests conducted by the DPRK (Democratic People’s Republic of Korea) are proof of this,” says UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, a strong advocate of nuclear disarmament.

Under the provisions of the CTBT, the treaty cannot enter into force without the participation of the last of the eight key countries.

Alice Slater, an Advisor with the Nuclear Age Peace Foundation and who serves on the Coordinating Committee of World Beyond War, told IPS: “I just think it’s a big distraction from the momentum currently building for the ban-treaty negotiations this fall at the UN General Assembly.”

Additionally, she pointed out, it will have no effect in the US where the Senate is required to ratify the CTBT for it to go into effect here.

“It’s ridiculous to do anything about the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty since it isn’t comprehensive and it doesn’t ban nuclear tests.”

She described the CTBT as strictly a non-proliferation measure now, since Clinton signed it “with a promise to our Dr. Strangeloves for the Stockpile Stewardship Program which after 26 underground tests at the Nevada Test Site in which plutonium is blown up with chemical explosives but doesn’t have a chain reaction.”

So Clinton said they weren’t nuclear tests, coupled with high tech laboratory testing such as the two football fields-long National Ignition Facility at Livermore Lab, has resulted in the new predictions for one trillion dollars over thirty years for new bomb factories, bombs and delivery systems in the US, said Slater.

Gerson told IPS a report from the Open Ended Working Group (OEWG) on Nuclear Disarmament will be considered at the upcoming General Assembly session.

The U.S. and other nuclear powers are opposing the initial conclusions of that report which urges the General Assembly to authorize the commencement of negotiations in the U.N. for a nuclear weapons abolition treaty in 2017, he added.

At the very least, by getting publicity for the CTBT UN resolution, the Obama administration is already distracting attention within the United States from the OEWG process, Gerson said.

“Similarly, while Obama may urge the creation of a “blue ribbon” commission to make recommendations on funding the trillion dollar nuclear weapons and delivery systems upgrade in order to provide some cover for reducing but not ending this spending, I am doubtful that he will move to end the U.S. first strike doctrine, which is reportedly also being considered by senior administration officials.”

Were Obama to order an end to the U.S. first strike doctrine, it would inject a controversial issue into the presidential election, and Obama doesn’t want to do anything to undercut Hillary Clinton’s campaign in the face of the dangers of a Trump election, he argued.

“So, again, by pressing and publicizing the CTBT resolution, U.S. public and international attention will be distracted from the failure to change the first strike war fighting doctrine.”

Besides a ban on nuclear tests, Obama is also planning to declare a policy of nuclear “no first use” (NFU). This will reinforce the US commitment never to use nuclear weapons unless they are unleashed by an adversary.

In a statement released August 15, the Asia‐Pacific Leadership Network for Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Disarmament, “encouraged the U.S. to adopt “No First Use” nuclear policy and called on Pacific allies to support it.”

Last February, Ban regretted he was not able to achieve one of his more ambitious and elusive political goals: ensuring the entry into force of the CTBT.

“This year marks 20 years since it has been open for signature,” he said, pointing out that the recent nuclear test by the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) – the fourth since 2006 — was “deeply destabilizing for regional security and seriously undermines international non-proliferation efforts.”

Now is the time, he argued, to make the final push to secure the CTBT’s entry into force, as well as to achieve its universality.

In the interim, states should consider how to strengthen the current defacto moratorium on nuclear tests, he advised, “so that no state can use the current status of the CTBT as an excuse to conduct a nuclear test.”