Eliminating the threat of nuclear weapons once and for all will require ending the threat of conventional war, too.

By John Horgan, October 6, 2017, Scientific American.

I hope that this year’s Nobel Peace Prize adds oomph to efforts to eliminate the threat of nuclear war—and war in general

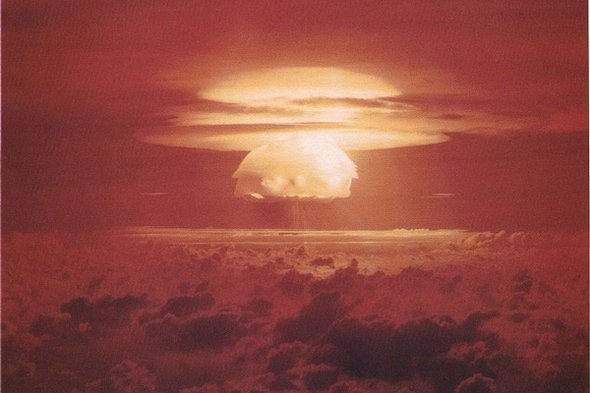

The Norwegian Nobel Committee announced today that it is giving the 2017 Peace Prize to the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN). The committee lauded ICAN for “its work to draw attention to the catastrophic humanitarian consequences of any use of nuclear weapons and for its ground-breaking efforts to achieve a treaty-based prohibition of such weapons.”

ICAN, based in Geneva, is a coalition of hundreds of activist groups around the world. The coalition was founded a decade ago to lobby for an international ban on nuclear weapons, called the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. In a vote at the United Nations last July, 122 nations, or about two thirds of all U.N. members, approved of the treaty.

According to the ICAN website, the treaty “prohibits nations from developing, testing, producing, manufacturing, transferring, possessing, stockpiling, using or threatening to use nuclear weapons, or allowing nuclear weapons to be stationed on their territory. It also prohibits them from assisting, encouraging or inducing anyone to engage in any of these activities.”

A nation that already possesses nuclear weapons must pledge to “destroy them in accordance with a legally binding, time-bound plan. Similarly, a nation that hosts another nation’s nuclear weapons on its territory may join, so long as it agrees to remove them by a specified deadline.”

Nine nations possess nuclear weapons: the U.S., Russia, Britain, France, China, India, Pakistan, Israel and North Korea. Between them, the U.S. and Russia account for the vast majority of the 14,900 warheads in existence. None of the nuclear-armed nations signed the prohibition treaty.

The Nobel committee acknowledges that “so far neither the states that already have nuclear weapons nor their closest allies support the nuclear weapon ban treaty. The Committee wishes to emphasize that the next steps towards attaining a world free of nuclear weapons must involve the nuclear-armed states. This year’s Peace Prize is therefore also a call upon these states to initiate serious negotiations with a view to the gradual, balanced and carefully monitored elimination” of all weapons.

In 2009, the Norwegian committee gave the Nobel Peace Prize to President Barack Obama for his “vision of and work for a world without nuclear weapons.” That prize turned out to be ironic. Obama approved a $1 trillion “modernization” of the U.S. nuclear arsenal, which critics fear could trigger a new arms race with Russia and hamper anti-proliferation efforts.

My colleague Alex Wellerstein, an historian and authority on nuclear weapons, whom I recently interviewed, doubts the feasibility of a ban. He notes that “the nuclear weapons states still feel that nuclear weapons are necessary for their security. Should they? That’s a really hard question to answer; there are many sides to it. But suffice to say: until the states with nuclear weapons feel that they live in a world where the lack of nuclear weapons will not affect their security or their prestige, they will hold onto them tightly. And that will have rippling effects.”

The logic of the nuclear states seems topsy-turvy to me. To my mind, none of us should feel secure as long as nuclear weapons still exist. Implementing a ban that can be verified and will not destabilize relations between nations won’t be easy. As long as nations feel threatened by each other, some will be tempted to rely on nuclear weapons as a defense. The solution to this dilemma is clear: We need to eliminate the threat of conventional war, too. Abolishing war between nations seems like a long shot now, but we have no choice but to seek it, so let’s start now. Donald Trump, I’m talking to you.