By David Swanson, May 2, 2019

Go right now and get yourself and the nearest house with a flag in front of it a copy of Roberto Sirvent’s and Danny Haiphong’s American Exceptionalism and American Innocence: A People’s History of Fake News — From the Revolutionary War to the War on Terror.

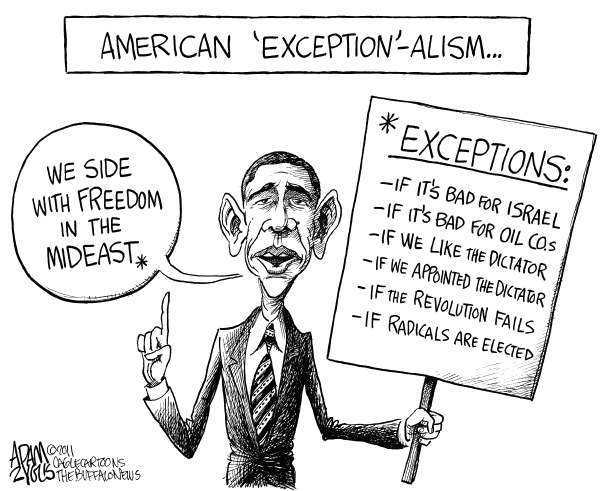

If this book had existed when I published Curing Exceptionalism, I would have said that reading it was part of the cure. The authors provide a rich survey and analysis of how people in the United States manage to believe themselves not only exceptionally qualified to break rules and commit crimes but also exceptionally innocent of all such behavior.

For these authors, appeals to “values” of “freedom” and “liberty” and “individual rights” are not just false because actions fail to reflect those values but also because those values have from the start been based on the enslavement and oppression of others. The origin myths of the “American Revolution” not only set aside slavery and genocide as footnotes, and depict an imperialist project as a rebellion against empire, but purport to describe a self-correcting system ever more inclusive, ever less hypocritical, so that revolution is made obsolete.

While I’ve asked people to begin using “we” to refer to global and local identities, rather than a militarized nationalistic one, Sirvent and Haiphong ask their readers to use “we” to bring past injustices into the present and recognize “our” complicity in settler colonialism. The two things are not, of course, incompatible.

This book makes the appropriate leap from the origin myths of the 1770s to those that have largely replaced them from the 1940s. Coming to terms with the real story of World War II is central to curing exceptionalism. One stumble, I believe, comes when the authors claim that the West only saw Hitler as an enemy when he applied cruel treatments to Europeans that were acceptable only for non-Europeans. This is true of post-WWII propaganda, of course, but a false account of Western actions during the war, and I think not what Aimé Césaire, whom they cite, had in mind. The U.S. government’s aims were exactly as imperial and had as little to do with human rights then as now. The governments of the West had refused to accept the Jews as refugees, despite Hitler’s claim that he would ship them all out on luxury cruise ships. The British and U.S. governments rejected peace activists’ demands that the Jews be evacuated. Each side of the war killed many more people by fighting the war than were killed in the camps. Not one scrap of Western propaganda mentioned rescuing Hitler’s concentration-camp victims until after the war was over. In fact, as Sirvent and Haiphong note, just two pages later: “By the time the U.S. entered the war full steam, only one goal mattered: to redesign the world in the interests of American monopolies, with Great Britain by its side.”

One of the most important chapters in American Exceptionalism and American Innocence is called “Should U.S. Imperialism Matter to Black Lives Matter?” The answer, of course, is yes, and the case is very well argued. The Black Lives Matter movement included internationalism and anti-imperialism from early, the authors write. This is reflected, I think, in the excellent Black Lives Matter Platform. But Black Lives Matter struggled, Sirvent and Haiphong recount, when Colin Kaepernick was widely criticized for protesting during the U.S. National Anthem — criticism which of course produced the widespread response that “We love flags and countries and wars too; that’s not what we’re protesting.” Sirvent and Haiphong rightly suggest that the protest should have included such targets, not as alternatives to police murders of black people, but as integral parts of the same problem.

Kaepernick was accused of being unpatriotic, but also of being ungrateful. Sirvent and Haiphong bring out the long history of demanding gratitude from those abused by — even enslaved by — the United States. I’m reminded of polling that found a U.S. majority believing that the people of Iraq were grateful for the destruction of their country. I also recall a strange sort of war opposition arising out of the realization that a war’s victims might not even be grateful. I suspect there is untapped potential there, and that informing the U.S. public that 40,000 human beings have already died of U.S. sanctions in Venezuela and that a war would kill huge numbers might not be as effective in the end as proclaiming a stubborn lack of gratitude among Venezuelans.

There is, after all, something unique, even exceptional, about certain U.S. habits of thought. It just isn’t something to be proud of.